|

Libertarianism and The Myth of the Closed Mind

PART I ‘The truth has not so little light as not to be perceived through the darkness of falsehoods.’ Galileo Galilei, 2001 [1633]. Dialogue Concerning The Two Chief World Systems. p. 488. 0. The Intellectual Strategy of Libertarianism Libertarianism, in particular anarcho-libertarianism, like any system of ideas that challenges the dominant ideology of its time, is of necessity a long-term propagandistic goal. It is emphatically not politics. Politics is the art of fishing for votes in the short term while taking the dominant ideology for granted. A successful politician has to convince the public that he embodies what they already believe and value and is better at expressing those values and beliefs and creating and acting upon policies guided by them. As David Hume put it: ‘Nothing appears more surprizing to those, who consider human affairs with a philosophical eye, than the easiness with which the many are governed by the few; and the implicit submission, with which men resign their own sentiments and passions to those of their rulers. When we enquire by what means this wonder is effected, we shall find, that, as Force is always on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them but opinion. It is therefore, on opinion only that government is founded; and this maxim extends to the most despotic and most military governments, as well as to the most free and most popular. The soldan of Egypt, or the emperor of Rome, might drive his harmless subjects, like brute beasts, against their sentiments and inclination: But he must, at least, have led his mamalukes, or praetorian bands, like men, by their opinion.’ (Essay IV. Of the First Principles of Government.)

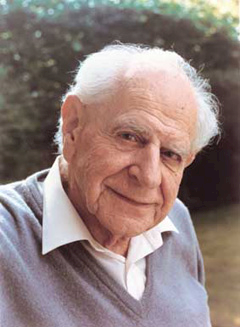

David Hume, who believed government was based All government depends on opinion: the opinion of right (legitimacy and social mores) and the opinion of interest (economic advantage). Politicians who flout this principle – for example, Enoch Powell and Barry Goldwater – are left by the wayside. Goldwater went head-to-head against the juggernaut of the New Deal and the welfare state ideology and lost the 1964 presidential election. Hume’s fundamental principle also applies to all other conventions, traditions and institutions. Suppose a radical group wished to abolish insurance. Also suppose that they could magically make all insurance companies and their buildings disappear. The next day, insurance would be back, just because most people regard it as both legitimate and in their interests – though perhaps with higher premiums on account of anti-insurance magicians. People simply take it for granted as a background assumption, just as democracy is taken for granted in the west as at least a necessary evil. Hume elaborates, when pushed to consider rejecting a given institution, people will cast about for a better alternative that can be installed without too great a cost. Seeing none, they will maintain the status quo. These things are part of the dominant ideology in the sense that for most people, they are things that they think in accord with rather than reflect on as objects for critical analysis, rather as the shopkeeper uses arithmetic without being concerned about Russell’s and Frege’s logicist project of deriving arithmetic from logic. Thus, if government is to be rolled back significantly or wither away completely, it is peoples’ most fundamental, unexamined opinions that must change. Only long-term argument can do this. For an enlightening application of Hume’s idea that ideological changes precede political changes (and not the other way round) see Stephen Berry’s excellent article ‘No Tears for the Fuhrer’, 1982.) In contrast to the politician, the anarcho-libertarian is presenting a system of ideas at odds with the dominant ideology. What could be more at odds with the common-sense talk at your local pub than Lester’s (2001) definition of libertarianism by his marvelous reversal of Mussolini’s definition of fascism: 'Nothing in the state, everything against the state, everything outside the state.’1 Having said that, it is a fortunate fact that people are tacitly classical liberal in their ordinary day-to-day dealings with other people: most people, most of the time, aren’t running off with each others property and bashing each other on the head when upset. There are many ways to persuade others to act in accord with one’s ideas and values: payment, coercion, deception, charm, love, hate, poetry, ridicule, ostracism or honest sound rational argument. However, only sound argument has a propensity for lasting impact, partly because people adopt a telling argument as their own. While the politician can, having achieved power, use coercion, bribery and deception to implement his policies, what does the anarcho-libertarian have at his disposal to achieve his goal? It has to be peaceful sound argument because this is both morally right and the only effective path to fundamental change in opinion. In contrast, force and deception and other means of persuasion are either ephemeral or last only as long as their costly application..’’2 Getting libertarians into politics provides a window for advertising the ideas of liberty, but there is always the danger that the compromises of politics may also subvert those principles. It certainly cannot be sufficient to bring about a libertarian society. At best, elected libertarians are the end result of decades of intellectual debate through books, journals, pamphlets and conferences. I’m not saying that one can’t use pioneering examples of libertarian societies to convince people of the benefits of liberty. For example, we might pursue the path of so-called ‘sea steading’, where we build a floating city or network of cities along classical liberal lines. But even presenting these pioneering efforts would require sustained and ingenious argument. Of course, many argue for minimal statism, the night-watchman state, which simply takes care of society-wide defence and perhaps the post office. However, given that our arguments may be discounted to a degree, it may be a better strategy even for the minimal statist to argue for the ideal of anarcho-libertarianism. Therefore, if the libertarian movement is not to loose morale or risk subversion or simply waste its energies, it has to feel confident in the power of bold rational argument, and also place the bulk of its effort there. Yet, there is a popular myth that might undermine this confidence, if not opposed: the myth of the closed mind. I wrote the book The Myth of the Closed Mind: Understanding Why and How People are Rational (2012. Open Court: Chicago) to explode the myth and contribute to a world of greater freedom and civilization. As libertarians, we ought to have a heightened awareness of a rising trend of cynical pessimism about the power of rational argument. Mass demonstrations, though useful as advertising, are useless by themselves to change or defend ideas. The spirit of mass unity demonstrations in France after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, seemingly to defend, at least in part, free speech, has faded somewhat for lack of the will to push good arguments against political correctness and laws over so-called hate-speech. The popularity of demonstrations is in no small degree due to a cynical pessimism about the power of rational argument. This is conspicuous with demonstrations against the holding of debates when they involve someone with unpopular opinions. Debate me, of course, but only when you agree with me. To those cynics I say: truth shines more brightly in the darkness of falsehoods. Unexamined falsehoods fester underground and still exert their influence in uncontrollable ways. 1. The Myth The myth of the closed mind is the idea that some people and some systems of ideas are irrational and therefore insulated from the impact of critical sound argument and truth. On this pessimistic view, humans are irrational and gross errors can always persist intact down the generations, safe from the damaging scrutiny of reason. This popular idea is a deep obstacle to the success of libertarianism. After all, if government is dependent on opinion, but that opinion is closed to argument, libertarian arguments may be seen as a waste of time, thus undermining confidence in pushing the arguments for liberty. The rise of political correctness and the idea that dangerous trends such as suicide terrorism can be controlled by suppressing free speech and invading peoples’ privacy on mass testifies to a widespread cynicism about the role of argument and the popularity of the myth of the closed mind However, this idea can be brought down by philosophical argument. I argue that people are rational in a number of respects that make them open to argument: they act according to their perceived means and ends, prefer truth and coherence in their beliefs, and take account of the opportunity cost and benefits of their actions. However, how do these preferences relate to argument? Most people, in western culture at least, think approvingly of rationality as the use of argument to justify our opinions or actions. But this is seriously wrong headed. I’m arguing that when people attempt to adjust their actions and beliefs to these standards of truth, coherence, efficiency etc., they are engaging in a form of argument called conjecture and refutation, not justification. In this trial and error process, our guesses are often rudely refuted. However, just because people prefer to be right doesn’t mean they can’t be wrong and still have impeccable rational inclinations and sensitivities. Searle (2001) overlooks this when he takes the frequent gaps between our reasons (beliefs about ends and means, costs etc.) and our actions (weakness of the will) as showing that people are not rational. My view is that humans are rational animals, not because we provide reasons for our theories and action plans, but because we can and ought to use reason to undermine them through criticism, a view developed by, among others, Karl Popper (1959), William Warren Bartley III (1984) and David Miller (1994 & 2006), Notturno (1999), Shearmur (2001). Stimulated by a problem, our ideas arise without justification and are then elaborated and put under the grill of unstinting criticism. The ethical motto of this critical rationalism is: ‘You may be right and I may be wrong, and with an effort, we may get nearer to the truth.’ It is a humble, but also bold approach, fuelled by a self-acknowledged optimism of fallible progress through the cooperative competition of debate. Debate is seen as an intellectual division of labour: you show me my faults and I’ll show you yours.

Karl Popper, powerful critic of justificationism

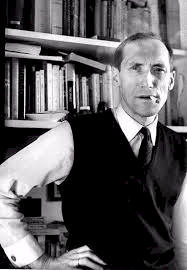

This view contrasts with a deep assumption in western philosophy and culture that Bartley called justificationism. This is the view that one should adopt all and only those positions that one can provide reasons or evidence for, whether by observation or the intellect. However, early on in the life of this precept, it was noticed that there was a problem. All arguments consist of premises and conclusion. It became clear that if one abides by the principle of justificationism, one ought to produce an argument for the premises, and an argument in turn for the premises of that argument, and so on ad infinitum. Aristotle was aware of this and supplied his theory of the intuition of essences to provide for ultimate premises to his syllogisms. Justificationism needs a stopping point, an authority of last call. Rene Descartes’ general criterion of truth as clear and distinct ideas and Francis Bacon’s induction of general laws from many and varied observations, were two main answers to this problem. Descartes and Bacon were important figures in the fight against the authoritarianism of uncritical traditions and institutions and bolstered the intellectual autonomy of the individual thinker. However, they transferred the source of authority from certain people and institutions to reason or experience, and as an unintended consequence, these became the ultimate dogmatic stopping points to debate. Their solutions were also flawed, as induction is a logical fallacy and many clear and distinct ideas are false. Bacon’s ultimate resort to empirical experience, though it avoided the infinite regress of argument, was left with the problem that since his inference to more and more general laws was itself an argument requiring first premises, it couldn’t get started because raw experience by itself is not a statement of a premise. Justificationism is based on a hunger for authority, certification and certainty, is thoroughly authoritarian and is well suited to the state’s monopoly of coercion. It inhibits the critical ethos inherited from Socrates, which follows the argument wherever it goes and rejects ultimate stopping points. After all, if one has justified a position, especially to the point of proof, why should one listen to any criticism? And if it’s a conjecture that can’t be justified or proven, then it may legitimately be neglected. Justificationism seeks ultimate sources of judgement, of the kind that led Barack Obama, referring to global warming, to announce in a tone of unchallengeable certainty: ‘The debate is over’, on the grounds that a sufficient number of scientists voted it so. (Apparently, science is seen as the drive to achieve certification through consensus and petitions, rather than the adventurous search for conjectural truth through unrelenting debate, in which it is often the lone brave voice that makes the important steps forward.) In contrast to this clamour for certainties, and drawing on the work of Popper, Bartley and Miller, I argue that such certifications and certainties are illusory, would be useless even if they could be had and that we can manage quite well without them. All knowledge is but a woven web of guesses which, though it may contain error, can be controlled by critical evaluation. All positions (beliefs, statements, proposals, theories) are criticisable in the sense that we can devise appropriate standards against which to test them. Knowledge advances through bold conjecture and ruthless criticism. This is not only logically sound, but we have a natural proclivity to think in accord with this scheme, though it may by degrees be enhanced or inhibited by argument and culture. Since this view happily starts with the acknowledgment that all premises are conjectures, it is unaffected by the dilemma of either embracing infinite arguments or committing to dogmatic stopping points. A superficial commentator might at this point ask how are we to know that we have really refuted any given conjecture? This is to confuse a refutation with its justification: refutations remain conjectural, but that does not show that they have not been correctly executed. Logically, conjecture and refutation faces no equivalent of the infinite regress that besets justificationism. In many cases, there is no problem in ascertaining the refuting instance(s). In science, one of the main goals of good experimental design is to make counterexamples easy to identify publically and reproducible, and only a rampant solipsist would argue that this is rarely or never possible. If someone disputes the counterexample, they’re perfectly at liberty to test it. For non-scientific theories, we may use the standards of logical coherence, consistency with theories that are scientific, or at least less problematic and the ability to address and solve the problem at issue. Many see irrationality wherever there is no accompanying certificate of justification. Religious zeal, suicide terrorism, passionate commitment to ideologies, and the result of various psychological tests are often cited to show that humans are fundamentally irrational. It is assumed that if people lack justification for their beliefs, then they must be closed to critical argument. For how would one argue against a position whose adoption is not based on evidence or reason? However, this is to confuse criticism and justification. It is assumed that if peoples’ beliefs are not connected with justification then they can’t really be about the truth and therefore closed to argument. For example, Sam Harris writes: ‘We can believe a proposition to be true only because something in our experience or in our reasoning about the world actually speaks to the truth of the proposition in question’…’As long as a person maintains that his beliefs represent an actual state of the world (visible or invisible, spiritual or mundane), he must believe his beliefs are a consequence of the way the world is. This by definition leaves him vulnerable to new evidence.’ (Harris, 2006, pp. 62 – 63.) The implication is that if a belief is not produced by a justification causally anchored in the world, it is not vulnerable to new evidence. On the contrary all beliefs - ‘justified’, caused by the world or not - are vulnerable when shown to be faulty. Once criticism is understood from a non-justificatory perspective, people adopting beliefs - whether out of unjustified zealotry or not - can be seen as perfectly rational and both logically and psychologically open to argument. Bartley propounded such a perspective: comprehensive critical rationalism, CCR. From this point of view, all positions, including this one are open to criticism. The purported truth of the position is what should interest us, not its futile justification or its origin. For example, it is irrelevant whether people adopt a religion (or any system of ideas) simply because these ideas happened to be around when they were young, they were excited by a charismatic leader, prompted by the constellations, they received a bump to the head or that they were stimulated by the nuances of tea leave patterns. What matters is whether those ideas are susceptible to critical argument and whether their promulgators would abandon them under the impact of criticism. Whereas justificationism sees criticism of a position as an attempt to show that it lacks justification, CCR separates criticism and justification, and attempts to show that the position fails to match the standard of truth. Often associated with this accusation of the irrationality of zealous religions and passionate ideologies is the assertion that people and ideas can be, not merely stubborn by degrees, but relentlessly immune to argument. The revered Polish thinker Leszek Kolakowski wrote: ‘Not only in the ‘socialist bloc’, where the authorities used every means to prevent information from seeping in from the outside world, but also in the democratic countries, the Communist parties had created a mentality that was completely immune to all facts and arguments ‘from outside,’ i.e., from ‘bourgeois’ sources.’ (Kolakowski and Falla 1978, p. 452)

Leszek Kolakowski, critic of communism In a similar vein, consider the words of the scholar of ideologies, D.J. Manning: ‘An ideology cannot be challenged by either facts or rival theories.’ (Manning 1976, p. 142) In my book The Myth of the Closed Mind I examine many supposed examples of irrationality and argue that they are all compatible with rationality. At the most general level, we are all rational in that, although we are infinitely ignorant, biased and always prone to error, we can, in principle, always correct our errors and then make continual progress. Rationality, as I’ve indicated, does not depend upon intellectual authority. Neither does rationality mean the absence of error, but the possibility of correcting error in the light of criticism. In this sense all human beliefs are rational: they are all vulnerable to being abandoned when shown to be faulty. Not only is error not a sign of irrationality, it is a tool of reason, because we use error to correct our theories. We actively seek error on two levels. Instinctively, we are born with a set of expectations and have a propensity to generate new expectations and ideas, which we correct and modify through sensory and intellectual revision. This contrasts with the justificationist’s silly ‘bucket theory of mind’, in which the mind passively absorbs information from the world through the senses. In our most developed critical institution, science, we use language to deliberately construct bold theories that take even greater risks of encountering error and being show to be faulty. It may take time to correct error, but much rain wears the marble.

"Pure empiricism is related to thinking as eating is to digestion and assimilation. When empiricism boasts that it alone has, through its discoveries, advanced human knowledge, it is as if the mouth should boast that it alone keeps the body alive." Some thinkers have insisted that the very absurdity of an idea, its retreat from rationality in any form, enhances its chances of surviving and reproducing itself through a population of minds. However, I argue that the more absurd a doctrine, and the more it hides from criticism, the less its ability to spread. There is a trade off between satisfying our preferences as rational creatures and safeguarding a doctrine or ideology from criticism. On the other hand, systems of ideas that appeal to our curiosity, logical and economic considerations have a comparative advantage in the battle of ideas. There is no guarantee that truth will win, only that, if promoted, it has at least a slight propensity to do so. But a slight propensity is all we need in the long run. Someone might object that at a sufficient level of generality there are more false theories than true ones, and so there is always the danger that the island of truth may be overwhelmed by a tsunami of competing false theories. My answer here is that the false theories are in competition with one another as well as with the truth, and so, to continue the metaphor, the false theories are more like separate waves, sometimes coalescing, but also sometimes destructively interfering with one another. The slight propensity for truth to win is also caused by the fact that reality is a mnemonic and so the purveyor of a true doctrine is continually reminded of its superiority by its veridical implications; a false theory can share in this strength only to the extent that it approximates the truth. (Percival 2012, pp. 120-129)

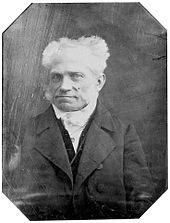

2. The Many-fold Toppling of the Citadel of Justificationism The citadel of justificationism has suffered many attacks, but here I’ll mention three of the most profound. The citadel of Justificationism has suffered three attacks, each one of which is logically sufficient to topple it: Plato’s story of the man in search of the city of Larissa; David Hume’s criticism of induction; Alfred Tarski’s and Kurt Godel’s work on the separation of proof and truth even in mathematics. The alternative philosophy of Critical rationalism is not only undamaged by the result of each attack, it embraces it. In the Meno, Plato told the story of a man who had to make a decision as to which of two paths to follow so that he would reach the city of Larissa. Plato’s aim was to explore the difference - if any - between knowledge and merely true belief. Plato imagined a situation in which the man made his decision based on merely true belief. Clearly, having the truth, the man would reach his desired destination. Plato then asked, would and should he have acted any differently had he chose to act not on merely true belief, but rather knowledge? Although Plato does not actually draw this consequence, it’s at least tempting for the critical rationalist to conclude (Miller 1994) that one can act no better than in the light of the truth - truth is sufficient, at least for practical purposes, and why not also for purely intellectual curiosity? Justification is otiose. David Hume (1711 – 76) (1978/1739, book 1,part 3, section 6) raised a fundamental problem for the inductive confirmation of universal theories of science and the prediction of new phenomena from other phenomena. Hume starts with a puzzle. Being a good empiricist, Hume begins: there is only one source of new knowledge: experience. Experience is our justification. However, our claims to knowledge seem to go far beyond what we can infer from experience. Hume does not use the word “induction,” but discusses what has become known as the principle of induction: “that instances of which we have had no experience must resemble those of which we have had experience, and that the course of nature continues always uniformly the same.” For example, all ravens of which we have had experience have been black. We therefore expect the next one also to be black. However, Hume, insists, this is deductively invalid. There’s no logical connection between one instance of any supposed kind and another instance. There’s nothing in logic that prohibits a world consisting of a trillion black ravens and one solitary white raven. Hume also pointed out that laws of nature are universal. They speak about the whole of space and time. Thus the statement “All ravens are black” covers everything in the universe that is a raven, all past, present and future. (In some modern accounts, each law of nature literally speaks about everything. [x] [fx ⇒gx]. For anything x, if x is f, then x is g.) A deductively valid argument is one in which if the premises were true then the conclusion must be true. For example, all owls are nocturnal; this bird in my garden is an owl; therefore, this bird in my garden is nocturnal. If we accept the truth of the premises, we are committed on pain of contradiction, to the truth of the conclusion. However, in the case of an induction, this is not correct, since no matter how many nocturnal owls one has observed, the very next one could be mostly active during the day and sleep at night. The general laws of nature lie beyond our inferences. Hume’s argument is reinforced by the observation that there have been many regularities we have observed without exception for hundreds or even thousands of years that have been rudely interrupted by an eventual exception. Consider the following examples. Newton’s theory held its position with many confirmations for about 250 years. However, Einstein’s new theory refuted it. For thousands of years it was thought that all life needs light to survive. However, in the last couple of decades we have discovered bacteria—so-called extremophiles—living far below the earth’s surface, which live on purely chemical energy (Gold 2001). To those who say that induction is justified because it has worked in the past, Hume replied that this would be to argue in a vicious circle. As a resolution to the puzzle Hume propounded, critical rationalists, starting of course with Popper (1959), have proposed that, first, we don’t infer our theories, we conjecture them freely in the context of current discussion and problems and then we keep the standard of experience, not as a justification of our theories, but as a tool with which to refute them. In effect, it is irrelevant where or how we get our theories, so long as we can control error within them by critical argument, in the case of scientific theories requiring them to be falsifiable by observation reports. Only deductive logic is involved. For example, if all owls are nocturnal, then this owl in my garden should be nocturnal; however, this owl is mostly active during the day; therefore, all owls are not nocturnal. This valid rule of deduction is called modus tollens. It’s important to emphasise that the traditional conception of knowledge as justified, true belief, although endorsed by some libertarians such as Leonard Peikoff3, has been toppled by the separation of truth and justification. Consider Tarski’s work, in which truth is radically separated from justification and certainty. In Alfred Tarski’s correspondence theory of truth, truth is a correspondence between a statement and the world. The sentence ‘Snow is white’ is true if and only snow is white. Tarski rehabilitated the Aristotelian concept of truth by defining truth in a way that avoided the so-called semantical paradoxes, such as the liar paradox. According to Tarski’s theory, it is perfectly sensible to say that a statement no one has even entertained, let alone put through a procedure of justification (say a random read-out from a computer) may, nevertheless, be true. One could also imagine some pebbles on a beach spontaneously forming a true sentence. Someone might object that the sentence would have to be interpreted by someone and therefore is inescapably subjective and therefore that truth is still linked to our subjective knowledge. However, all that is required is that the sentence is interpretable and that alone does not make it subjective. A spade, no doubt, has to be interpretable as a spade, but clearly a spade is not a subjective state. Tarski’s work also proved that there is no general criterion of truth by proving that there is no procedure for classifying as true all the true statements of arithmetic and all the false ones as false. Clearly, Tarski’s work severs truth from human subjective states or procedures of justification. Tarski’s result allows for the possibility of finding a criterion of truth in various small domains, in the sense that if one were to apply one of them correctly one would systematically identify true statements. However, there is a stubborn remnant of conjecture here, for finding such criterions in the first place is a matter of creative conjecture and their application is fraught with the possibility of human error. A similar point may be applied to attempts to seek, not proof or conclusive justification, but partial support for theories. For example, in probabilistic accounts of support. For these attempts always presuppose some background assumptions (i.e., conjectures) about the law-like structure of the world in order to work. In other words, they are assuming that a lot of the scientific work has already been done. Kurt Gödel reinforced Tarski’s main result when he proved that truth and proof are separate in mathematics, long felt to be the realm of unassailable and complete proof, by showing that if arithmetic is consistent, then there must be un-provable but true mathematical statements. This is Gödel's first incompleteness theorem, presented in Gödel's 1931 paper On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems I.

Kurt Gödel, creator of the incompleteness theorems, The profound consequences of these discoveries, despite the neglect of the justification industry, are still rolling out. As science uses mathematics in its derivations, it’s clear that these results aren’t confined to the lofty realms of metamathematics. (For the collapse of certainty within mathematics, see Kline 1980.) Today you would be hard pressed to find a philosopher who holds that we can prove our theories. However, many have either opted for a cynical relativism, in which anyone’s ‘truth’ is as good as any one else’s, or have sort refuge in so-called partial justification (probabilistic support) and schemes for simply making our beliefs coherent (Bayesianism)4. Briefly, probabilistic support is actually an odd thing to hanker after, as probability has no relation to truth and varies inversely with the informative content of our best theories, such that under plausible interpretations, universal theories have zero probability. Adopting probability as a measure of support leads to other absurd consequences. For example, both Newton’s theory and Einstein’s theories are, a justificationist would suppose, well supported. If probability is the measure of that support, then – as probabilities vary between 0 and 1 – each of them must have a probability of more than ½. Now Einstein’s and Newton’s theories, though agreeing on much, are actually inconsistent. Therefore, the probable support of the statement ‘Either Newton or Einstein’, according to the probability calculus is the sum of the two, and should therefore be more than 1! (Popper 2009, p. xxiv.) For justificationists these results are devastating. In contrast, critical rationalism is unperturbed; indeed, it embraces these results because they reinforce the point that the pursuit of truth without justification is a meaningful and feasible project. The perspective of critical rationalism has two favourable implications for a critique of the state. It helps us to see that all ideas are amenable to reason, thus giving a fillip to the libertarian approach to changing society through peaceful argument and debate in a context of free speech, and it also shows us where to target our criticism of authoritarian obstacles to our vision, such as political correctness. I’m not saying that one needs to be a critical rationalist to be a libertarian, although, as shown by J. C. Lester in his Escape from Leviathan, they do mesh beautifully at many points. Neither am I suggesting that a libertarian society must consist of a majority of critical rationalists. Most people, while dabbling occasionally in philosophy, live their lives without an abiding, burning interest in any intellectual system whatsoever. Such an obsession will always be confined to a small minority, the intellectual leaders of society. My point here is that it is a much better ally than a justificatory approach dealing with the demoralising myth of the closed mind. (To be continued) In Part II of this article, armed with the critical rationalist method, I will run through the main arguments for the closed mind, such as Orwellian newspeak, closed linguistic frameworks, immunising stratagems, and explode them one by one. Bibliography. Ariely, Dan. 2009. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions; Barkow, J. Cosmides, L. and Tooby. J. 1995 [1992]. The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. New York: Oxford University Press. Brafman, O. and Brafman, R. 2008. Sway: The Irresistible Pull of Irrational Behaviour. New York: Random House. Berry, Stephen. 2001 [1982]. ‘No Tears for the Fuhrer.’ Free Life. Vol. 3 No. 4. London: Libertarian Alliance. Burton, Robert. 2008. On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even when You’re Not. St. Martins. Dawkins, Richard. 1990 [1976]. The Selfish Gene. Oxford University Press. Edelstein, Michael R. & Steele, David Ramsey. 1997. Three Minute Therapy. Aurora, Colorado: Glenbridge Publishing. Galilei, Galileo. 2001 [1633]. Dialogue Concerning The Two Chief World Systems. p. 488. New York: Modern Library. Gardner, Dan. 2009. Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear. London: Virgin Books. Glover, Jonathan. Oct 9, 2011. “On systems of belief", Philosophy Bites Podcast. Gold, Thomas. 2001 [1999]. The Deep Hot Biosphere: The Myth of Fossil Fuels. New York: Copernicus Books. Gopnik, Alison M. Meltzoff, Andrew N. William, Patricia K. Kuhl. 1999. Scientist in the Crib: What Early Learning Tells Us About the Mind. Morrow and Company Inc. Gödel, Kurt. 1931. ‘On Formally Undecidable Propositions of Principia Mathematica and Related Systems I.’ Harris, Sam. 2006. The End of Faith: Religion, Terror and the Future of Reason. London: The Free Press. Hayek, F, A. Sep. 1945. "The Use of Knowledge in Society." American Economic Review. XXXV, No. 4. pp. 519-30. Hume, David. 1978. [1739]. A Treatise of Human Nature. Oxford: Ford University Press. ___________. 2012 [1758]. Essay IV. ‘Of the First Principles of Government.’ In Essays: Moral, Political, and Literary (Volume I of II). Digireads.com Publishing. Kline, Morris. 1982. Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty. Oxford University Press. Kolakowski Leszek & Falla, 1978. The Main Currents of Marxism. Oxford: Clarendon. Leeson, Peter. Anarchy Unbound: Why Self-Governance Works Better Than You Think. Cambridge University Pres. Lester. J. C. 2012. [2000]. Escape From Leviathan: Libertarianism without Justification. Buckingham: The University of Buckingham Press. Manning, D. J. 1976. Liberalism. Dent. Marcus, Gary. 2008. Kluge: The Haphazard Construction of the Human Mind. London: Faber and Faber. Miller, David, W. 1994. Critical Rationalism: A Re-statement and Defence. Chicago Open Court. __________. 2006. Out of Error: Further Essays on Critical Rationalism. London: Ashgate. Notturno, Mark Amadeus. Science and the Open Society: In Defense of Reason and the Freedom of Thought. Central European University Press. Pape, Robert. 2005. Dying to Win. New York: Random House. Percival, Ray Scott. 2012. The Myth of the Closed Mind: Understanding Why and How People are Rational. Chicago: Open Court. Polanyi1, Michael. Midway Repr. 1981 [1951]. The Logic of Liberty: Reflections and Rejoinders. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Popper, Karl. 1972, 6th revised edition. [1934]. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. London: Hutchinson. __________. 2009. The Two Fundamental Problems of The Theory of Knowledge. London: Routledge. Searle, John. 2001. Rationality in Action. Massachusetts: MIT. Seligman. E. P. Martin. 2007. What you Can Change and What You Can’t: The Complete Guide to Self-Improvement. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing. Shearmur, Jeremy. 2001. Hayek and After: Hayekian Liberalism as a Research Programme. London: Routledge. Wason, Peter. 1966. Reason. In B. M. Foss (Ed.). New Horizons in Psychology. London: Penguin. Whorf, B. L. 1956. Language Thought and Reality: Selected Writings of Benjamin Lee Whorf. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. William Warren Bartley III. 1984. Retreat to Commitment. Chicago: Open Court. Vedantam, Shankar. 2010. The Hidden Brain: How Our Unconscious Minds Elect Presidents, Control Markets, Wage Wars, and Save Our Lives. New York: Random House. 1 This reverses Benito Mussolini's definition of fascism (as quoted in The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Political Thought's entry on 'fascism' [Miller 1987, 150]). Anarcho-libertarianism, or private-property anarchism, is the opposite of fascism. 2 Things are a little more complicated than this suggests. It might be thought that the supposedly non-argumentative methods of persuasion I’ve mentioned here are counterexamples to the thesis of the rational mind. However, on closer inspection, they are better described as either insinuated tacit (or truncated) arguments or assumptions.. For example, ridicule: I’ll make you a laughing stock if you don’t toe the party line. In other words, these seemingly mindless prods and cajoling work by the mind’s ability to reason about propositions and logic, and are therefore open to critical argument, although, being partly hidden, they may take some shrewd guess work to pin them down. One of the most important characteristics of explicit arguments - say, arguments for liberty - is that, once produced, they have a life of their own. They can spread through a population of minds like viruses. Both Popper (with his World 3) and Dawkins (Memes) emphasised the importance of this autonomy of ideas. Belief is - though important - but one factor in their spread or demise, but it is undoubtedly a propitious moment in the life of an idea when that idea is spoken or written down. 3 Note that Peikoff’s knowledge of standard logic is sorrowfully lacking. For example, on his website he defines deduction as ‘the application of a generalization to particular cases’. Sometimes it is; sometimes it is not. He must never have come across Modus Tollens. Modus Tollens, as just described, is a deduction from a particular (a counterexample) to a generalization (the theory thus refuted). In general, a deduction is an argument in which, if the premises were true, then the conclusion must also be true. With regard to his ‘induction’, Peikoff is impressed by the illusion of generalization from particulars that we all seem to be engaged in. We see one or two black ravens, and seemingly infer by induction that all ravens are black. This illusion arises from the fact that we come to experience, not as cognitive blank slates, but rather already armed with general expectations, even from birth, about the world. We are importing into our inferences about birds generalizations to the effect that all living things of a kind will be the same in some respects, such as color. It then seen to be either a deduction, not induction, when we jump to some generalizations or a new conjecture simply prompted by observation. A child sees a frog squashed in the road, revealing its insides. The child would be astonished if it then sees another frog whose insides are filled with glass marbles.

4 There are many variants to Bayesianism, but the key contrast with Popper’s view is that they all eschew the search for truth as such and, as Miller (1994) points out, this makes it a mystery how it alone could possibly illuminate why scientists actively propose new bold hypotheses and then actively search for new evidence. The Bayesian can hardly say that the scientist just waits for new evidence to present itself and then adjusts the probabilities for coherence and apportion a suitable degree of confidence. If the Bayesian says that we seek new evidence to increase the support or confirmation of the theory, then we are right back to the debacle with Hume’s and Popper’s arguments against induction.

|

|