|

Richard Cobden and British Foreign Policy (The text of a talk given by Stephen Berry to the Libertarian Alliance in October 2015)

Cobden was born in 1804 near Midhurst in Sussex. He seems to have had the similar childhood and youth to that portrayed so ably by Charles Dickens in David Copperfield. His family endured various hardships, losing their farm in 1814. Minimal schooling was followed by work in the warehouse of his uncle at the age of fifteen. Eventually, Cobden became a commercial traveller for his uncle's business. Cobden seems to have been closest to his brother Fred, who helped Richard in his various business ventures. Cobden was fond of his brother, but seems to have regarded him as something of a waster and rather feeble. My impression was that Fred was in fact, just an average guy, totally unexceptional ‒ just the opposite to his more dynamic brother.

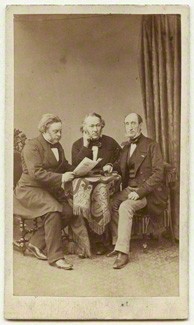

Richard Cobden Cobden's life picked up speed when he moved to Manchester in 1832. Manchester was the city of the future in the first half of the 19th century. Cobden wrote to his brother, "Manchester is the place for money making business. It is there that everyone of us must sooner or later go." Asa Briggs, the historian, called it, "the shock city of the age". It was in Lancashire that Cobden set up his own calico works. The new firm prospered and soon had three establishments – the printing works at Sabden near Clitheroe and sales outlets in London and Manchester. Evidently, Cobden's earnings in the firm were typically £8,000-10,000 a year, quite a sum for those days. Cobden could simply have remained a successful business man, but his ambitions were more considerable. Already writing under the byname Libra, he published many letters in the Manchester Times discussing commercial and economic questions. In 1835 and 1836 he published two noteworthy pamphlets, England, Ireland and America and Russia. Immediately their merit was clear. Cobden was recognised as someone of significance. John Morley, the biographer of Cobden, wondered how someone who had barely written before could have produced such accomplished literary works. Edsall, another biographer, states that Cobden had in fact presented a play for production at Covent Garden in his youth, so Cobden was not a totally new recruit to literature with these pamphlets. The two pamphlets advocated the principles of peace, non-intervention, retrenchment and free trade, ideals to which Cobden remained faithful all his life. Some of his best quotes are in these two pamphlets. It is "labour, improvements and discoveries that confer the greatest strength upon people ...by these alone and not by the sword of the conqueror can nations in modern and all future times hope to rise to power and grandeur." The key to any nation's prosperity and power lay not in conquest but in commercial supremacy. "Cheapness ... will command commerce; and whatever else is needful will follow in its train." The pamphlets included an attack on the doctrine of the balance of power which dominated thinking in British foreign policy in the 19th century. One of the major aims of British foreign policy in the 19th century was to prop up the Ottoman Empire against the Russians. Like today in Syria, all manner of horrors were imagined if the aims of the Russians were not thwarted ‒ including the Russians threatening India. Cobden would have none of this. If Turkey were to collapse as a result of its backwardness and inertia, Cobden was convinced this would benefit Britain, a great commercial and manufacturing power. Any modernisation of backward lands, whether by Russia or anyone else would be in the UK's interests. Cobden pointed out that Russia's advance to the Black Sea had actually increased UK trade in that area. Cobden also saw the New World, and especially the U.S., as a fine example to set against Europe. The emergence of an independent western hemisphere had revolutionised the world economy and shown up the closed economies of Europe. "The new world is destined to become the arbiter of the commercial policy of the old" was his way of putting it. The Atlantic, not the Mediterranean was to become the new fulcrum of power, something the parochial Europeans failed to see. By rendering the old mercantilist policy outmoded, America also made the traditional foreign policy outmoded. America set an example ‒ at least in the 19th century ‒ of free trade, no imperial responsibilities and a non-interventionist foreign policy. With a navy smaller than the UK's, America enjoyed a secure and steadily growing commerce. It served as an example to the UK. Britain too, could turn its back upon the sea of troubles that was Europe and Empire and concentrate on economic growth. The first two pamphlets may be the best of all Cobden's writings. They propelled him into politics and he stood as an MP for Stockport in 1837. Though he was defeated, he immediately threw himself into the formation of the Anti-Corn Law League in 1838.

The Corn Laws were taxes on imported grain designed to keep prices high for cereal producers in Great Britain. They imposed steep import duties, making it too expensive for anyone to import grain from other countries, even when food supplies were short. The laws were supported by Conservative landowners and opposed by industrialists and the workers. The Anti-Corn Law League was responsible for turning public and ruling-class opinion against the laws.

Cobden and later John Bright were the leading campaigners of the League. Cobden's case for the repeal of the Corn Laws was fourfold:

The only barrier to these four desirable solutions was the ignorant self-interest of the landlords, the 'bread-taxing oligarchy, unprincipled, unfeeling, rapacious and plundering'. In 1841 after Sir Robert Peel had defeated the Melbourne ministry in parliament, a general election was held and Cobden was returned as the new member for Stockport. Over the next five years Cobden and Bright pursued a vigorous propaganda campaign against the Corn Laws, both inside and outside parliament. The League was one of the first, if not the first powerful national lobbying group in politics. Consistency of purpose, well funded, very strong local and national organization and single-minded dedicated leaders were its hallmarks. The League was a large, nationwide, middle-class moral crusade which was eventually successful. Repeal of the Corn Laws passed the House of Commons on 16 May 1846 by 98 votes. The immediate precipitating cause was the Irish Famine, but the intellectual spadework had been done by the League. What next was the question for Cobden? He decided to campaign for peace and retrenchment. But first he had to sort out his own finances before he got round to those of the country. The work with the League meant that Cobden had effectively given up management of his calico firm. By the late 1840s, the firm was in great difficulty. It was only a public subscription of £80,000 which rescued Cobden and enabled him not only to continue in politics, but also buy the old family home at Dunford, Sussex. Cobden's record as an investor was decidedly spotty. He invested in real estate near Manchester and lost. Nothing daunted, in the middle of the 1850s he decided to invest in America's future and bought stock in the Illinois Central Railroad. Cobden did not regard this as a speculative investment as the company was backed by a land grant from the state. It was the value of this land which attracted Cobden. "It is not a railroad speculation," he told his financial advisor, "but the acquisition of a landed estate more than double the area of Lancashire..." So certain was Cobden of the ultimate value of the stock that he sold everything he had to sell, borrowed all he could, and secured as many shares as possible. In 1857 the Illinois stock dropped 40 per cent in the panic of that year. If this were not enough, the stock was not fully paid up. But when Cobden was told to sell up in 1858, he resisted. There was nothing for it. His friends had to pay the calls on his shares. It seems that Cobden had the average punter's approach to investment: Please give me a tip on the share which will make my fortune. Unfortunately, this approach has as much chance of working as has a demand for tip on the ticket which will win the lottery. During the 1850s, Cobden was the foremost critic of British foreign policy. On the establishment of the Second French Empire in 1851–1852 a violent panic, fuelled by the press, gripped the public. Louis Napoleon, the new French leader, was represented as contemplating a sudden and piratical descent upon the British coast without pretext or provocation. By a series of speeches and pamphlets, in and out of parliament, Cobden sought to calm the passions of his countrymen. In doing so, he sacrificed the great popularity he had won as the champion of free trade and became for a time the best-abused man in Britain. Later, Cobden wrote another pamphlet on the recurring crises with France and named it The Three Panics. an Historical Episode. These refer to the French invasion panics of 1847-48, 1851-52 and 1859-60. Cobden also protested concerning annexations in Burma. In early 1852, the government of India invaded the coastal provinces of Burma. Cobden had not the slightest doubt that the British Indian government was at fault. Many of the merchants' complaints appeared frivolous and the British naval commander in Rangoon seemed to have acted like the proverbial loose cannon. In 1853 he wrote a piece, How Wars are got up in India, with information largely taken from published government documents. Around this time, Cobden reluctantly admitted that his peace movement could never be the equal in strength of the League. He said that the same people who were prominent against the Corn Laws would not form the vanguard in other outdoor agitation. Each movement required its own personnel. The Anti-Corn Law League was a coalition of the middle and working classes ‒ a wide base difficult to repeat. At the beginning of 1857 news from China reached Britain of a rupture between the British governor in Hong Kong (Bowring - an old free trader) and the Chinese governor of the Canton province. It concerned a small vessel called the Arrow. This dispute had resulted in the British destroying river forts, burning 23 ships belonging to the Chinese Navy and bombarding the city of Canton. After a careful investigation of the official documents, Cobden became convinced that the British had behaved incorrectly. He brought forward a motion in parliament to this effect, which led to a long and memorable debate, lasting over four nights, in which he was supported by William Gladstone, Lord John Russell and Benjamin Disraeli, and which ended in the defeat of Lord Palmerston by a majority of sixteen. Cobden was less successful with regard to the Crimean War (1854-56). From the outset he opposed this war. At this distance it seems incredible that his resistance to the war, which is now regarded as a colossal blunder (on a par with the Boer and Iraq wars), should have subjected him to so much criticism. Opposition to the war cost both Cobden and Bright their parliamentary seats and convinced them both that they would never speak out against a war whilst it was in progress. Cobden wrote one of his best pamphlets What Next -- And Next in January 1856 as peace proposals were being made to the Russians by Austria.

Confronting public sentiment Cobden, who had travelled in Turkey and had studied its politics, was dismissive of the outcry about maintaining the independence and integrity of the Ottoman Empire. He denied that it was possible to maintain the Ottoman Empire, and no less strenuously denied that it was desirable. He believed that the jealousy of Russian aggrandisement and the dread of Russian power were absurd exaggerations. He maintained that the future of European Turkey was in the hands of the Christian population, and that it would have been wiser for Britain to ally herself with them rather than with what he saw as the doomed and decaying Islamic power. History proved him right on this. At the end of What Next -- And Next Cobden noted that the allies were demanding that Russia should have only so many warships in the Black Sea. Cobden said that it was ridiculous to try to specify what Russia might or might not do in its own waters and on its own territory. Diminutive Greece may submit to the Don Pacifico outrage, but a first class power like Russia should be looked at quite differently. When we look at recent events in Greece and the Ukraine, these remarks might seem to contain an echo 150 years later. Both Cobden and Bright got their seats in parliament back in 1859. Cobden declined to serve in Lord Palmerston's new administration but he did say was willing to act as its representative in promoting freer commercial trade between Britain and France. Cobden's and Palmerston's previous frosty relations made a government post impossible for Cobden. The negotiations for an Anglo-French commercial treaty had originated with Cobden, Bright and Michel Chevalier. Towards the close of 1859 he called upon Lord Palmerston, Lord John Russell and Gladstone, and signified his intention to visit France and get into communication with Louis Napoleon of France on the matter of a free trade treaty. On his arrival in Paris Cobden had a long audience with Louis Napoleon in which he urged many arguments in favour of removing those obstacles which prevented the two countries from being brought into closer dependence on one another. He succeeded in making a considerable impression on the emperor's mind in favour of free trade. Cobden was then officially requested by the British government to act as their plenipotentiary in the matter in conjunction with the British ambassador in France. The negotiations proved a very long and laborious undertaking. Cobden had to contend with the bitter hostility of the French protectionists. Worse, while he was in the midst of the negotiations, Lord Palmerston brought forward in the House of Commons a measure for fortifying the naval arsenals of Britain, Palmerston introduced this with a warlike speech, pointedly directed against France as the source of danger of invasion and attack against whom it was necessary to guard. This produced irritation and resentment in Paris and, and but for the influence which Cobden had acquired, the negotiations would probably have been altogether wrecked.

On the successful conclusion of the treaty, honours were offered to Cobden by the governments of both the countries. Lord Palmerston offered him a baronetcy and a seat in the privy council, and the emperor of the French would likewise gladly have conferred upon him some mark of favour. But with characteristic disinterestedness and modesty Cobden declined all such honours. In fact, Cobden was annoyed by the conduct of Palmerston during the negotiations and wanted to be free to criticise Palmerston's aggressive foreign policy. Cobden's efforts in furtherance of free trade were always subordinated to what he deemed the highest moral purposes: the promotion of peace on earth and goodwill among men. This was also his hope in respect of the commercial treaty with France. When the American Civil War threatened to break out in the United States, Cobden was mortified. But after the conflict became inevitable his sympathies were wholly with the Union because of the perception that the Confederacy was fighting for slavery. His great anxiety however, was that Britain should not be committed to any intervention during the progress of that struggle. Both Bright and Cobden were sympathetic to the cause of the North. Bright fully supported the North in the war. Cobden at first thought the North should let the South go. Slavery was not only evil, but was doomed economically and the North would in any case dominate in the long run. Cobden wrote to an American friend in the summer of 1864, "There is a constant struggle in my breast against my paramount abhorrence of war as a means of settling disputes ... If it were not for the interest which I feel in the fate of slaves ... I should turn with horror from the details of your battles, and only for peace at any terms. As it is, I cannot help asking myself whether it can be within the designs of a merciful God that even a good work should be accomplished at the cost of so much evil in the world." As far as I can see, Cobden and Bright did not differ on much, but when they did, Cobden was right: a) Instead of peace and retrenchment, Bright was keener on a campaign to widen the franchise. Cobden was dubious as to where wider democracy would lead. b) Bright favoured using the British Empire as a means to advance their causes. Cobden stated that the Empire could not last and should be disbanded. c) The differing views on the American Civil War just outlined. The American Civil War was Cobden's last major issue. For several years Cobden had been suffering severely from bronchial irritation and had difficulty in breathing. He had spent several winters abroad. In 1860 he went to Algeria, and every subsequent winter in England he had to be very careful and confine himself to the house, especially in damp and foggy weather. On 2 April 1865 he succumbed to this weakness and died peacefully at his apartments in London. Cobden's Thoughts on British Foreign Policy"Cobden was the most original and profound of Radical Dissenters;" remarked A.J.P Taylor on page 50 of his book The Trouble Makers. Cobden's view on a couple of the main pillars of British foreign policy is interesting. Cobden rejected the Balance of Power dogma which governed British foreign policy throughout the 19th century. This was highlighted by the so-called his radical approach to the 'Eastern Question'. This article of faith featured Britain propping up the Ottoman Empire against the Russians and was part of the fixtures and fittings of the 19th century foreign policy landscape. If Turkey collapsed it was presumed Russian troops would soon be marching down the Hindu Kush. Cobden maintained it was a gross fallacy that the UK had an interest in maintaining the "fairest regions of Europe in barbarism and ignorance ‒ that we are benefited because poverty, slavery, polygamy and the plague abound in Turkey ..." Russia was capable of becoming a modern state and this was welcome. In fact, the Ottoman Empire did collapse at the end of the First World War without the catastrophic consequences to British interests which had been forecast. A later prime example of where the balance of power doctrine can be questioned concerns British intervention in World War One. It was held axiomatically by the British Foreign Office that Germany should not dominate the European continent and this was the main reason why UK entered that war. Amusingly, one of the war aims of the German chancellor in 1914, Bethmann Hollweg, was the formation of a customs union on the European continent which he believed would be dominated by Germany. But the UK seems to be able to live with this actuality now and not judge it to be a casus belli.

But what of Britain's responsibility for the sacred cause of universal liberty? First, Cobden denied GB's moral superiority in this regard. Do the British supply both the virtue and wisdom to perform such a role? Much needs to be done in Britain. "It is to this spirit of interference with other countries, the wars to which it has led, and the subsequent diversion of men's minds from home grievances, that we must attribute the unsatisfactory state of the mass of our people." Cobden maintained that the British aristocracy was essentially warlike. It was nothing more than a delusion that we were a peace-loving nation. So the first principle of Cobden's foreign policy was non-intervention. Britain should set a good example at home. He did not mind the use of financial sanctions from the private sector to influence a foreign country ‒ as was the case with Russia in 1849. But at heart he knew that the key to world advance was "as little intercourse as possible between Governments; as much connexion as possible between the nations of the world." In the Don Pacifico debate of 1850 he said: The progress of freedom depends more upon the maintenance of peace, the spread of commerce, and the diffusion of education, than upon the labours of cabinets and foreign offices. Such was Cobden's success that, according to Taylor, Cobden was the real foreign secretary of the early 1860s. The Commercial Treaty with France, international arbitration and an agreed limitation of armaments were all Cobden initiatives. In the Schleswig-Holstein war of 1864, the British government never looked like intervening. This was despite the fact that Denmark was easily accessible to sea power and (purportedly) 'the freedom of the Baltic' was at stake. It did not end there. Between 1864 and 1906, no British government seriously contemplated armed intervention on the continent of Europe. This record of non-intervention compares well with the serial bungling of the last ten years or so. Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria seem to be perfect examples of the failure of the politics of foreign interference, to be compared with the Crimean War in their waste and failure. Cobden's favourite toast was to no foreign politics. That should also be ours.

|

|