The Ten Worst Books of All Time (Part Two)

![]()

By OLD

HICKORY

The Ten Worst Books of All Time (Part Two)

6). Das Kapital (1867)

Karl Marx

Marx thought we could have production directly for use, without a social criterion of cost, such as money. He failed to see that profit was an almost sound social criterion of economy; not foolproof maybe, but about as good as it gets.

Most Marxists indulge in the hyperbole that the market is not production for use or need but rather only for profit. However Marx quite explicitly defines a commodity as production for use as well as for exchange and profit; indeed, he says that the latter needs to meet some use or utility or need to sell in any case. So the Marxists’ hyperbole is not consistent with their special book – as well as being clearly unrealistic. They need to say it is not directly for use if they want to conform to the book, but clearly the hyperbole they use in their propaganda is vital to their case. They might try to apologise that it makes for clear propaganda to simplify in this way. But that this qualification makes for useless propaganda shows up the fact that the propaganda they do daily use is in the vulgar sense of mere lies, for their actual case, in this respect, is no case against the market at all. The market institutionally gears all who produce on it to aim at the satisfaction of others rather than of their own selfish needs but this is labelled as selfish by those who oppose the market as it is production for profit. But it is exactly profit that gears production to the needs of others. It is just as well that the Marxists know of no alternative to the profit or the money system.

So we already have production for use. The Marxist case is merely that production is not directly for use. Indeed, their case is usually against the need for economy itself, though the Marxists may well respond by saying that this is the necessary hyperbole of practical propaganda. But there are faults in their theory as well as in their propaganda. Moreover, it is not clear that we can have a system of production directly for use in the mass urban society without the need of a criterion of social economy, such as money is today. Nor is it clear that true faults have been found in the indirect production for need, by Marx; or by anyone else. In Socialism (1922) Ludwig Von Mises put forward the economic calculation argument. He held that the socialists were not even realistically considering the problem, that they knew of no alternative to the market and were therefore, criticising it in a completely impractical way, as a mere end in itself. A more up to date discussion that is clearer than Mises can be found in From Marx To Mises (1992) D.R. Steele.

The socialists who followed Marx, at least nearly all of the serious ones, were merely moaning about reality for the sheer sake of it. Socialism did not exist, not even in theory. It was a complete unknown. The USSR was a form of capitalism. It had wages, labour and capital, all the vital things that Marx condemned as bourgeois, as well as money. Contra what was supposed to be the case, there was no effective central planning in the late USSR. This argument of Mises posed a massive problem for those who thought there was an alternative to the market system. A solution to it remains unknown today. Indeed, few if any socialists have ever thought about the problem in a serious or a realistic way. They were merely confused in thinking that they knew better. A given Marxist was not just ignorant, we are all ignorant to some extent, but Mises had shown that Marxism itself was the creed of an ignoramus viz. that the experts of Marxism had all overlooked vital facts that they should have been able to deal with had their creed been viable.

I do not think that Marx was a bad man, but he was very wrong-headed. He adopted the tyro idea that central planning just had to be superior to anarchy and he ignored all the signs that this idea was false in all his vast, and prolonged, readings in economics. Marx produced Capital (1867) that might be thought of as being in four volumes, if we take as the fourth volume the three rather large volumes today called The Theories of Surplus Value. Even Engels did not get round to publishing this work, it being passed on to Karl Kautsky to work on. This made Kautsky the number three Marxist authority up to 1914.

Marx's 1850s notes were finally fully published in the 1970s as The Groundwork [Grundrisse] that added yet another thousand, or so pages, once more displaying the very extensive reading that he did. He was reluctant to publish volume one in 1867, doing so only because Engels insisted. If the story that Marx was affected by the marginal revolution of the early 1870s, that saw the sort of theory he called “classical” (to do with labour inputs making an objective value in output) being rendered defunct, replaced by a new version of what he called the vulgar theory (to do with the customers subjective value and without a labour theory or “scientific” foundation for supply and demand) then he might not have published at all had Engels neglected his insistence for a few more years.

Marx's theory of exploitation was almost a red herring as he freely agreed that communism would still exploit the workers, though no longer as a class or interest group, or no longer as the proletariat [but he was wrong that the workers ever were such a class, or economic interest group]. Exploitation would still be needed in the new society in order to care for the very young and the very old, amongst other socially needed projects or things that would be deemed needed in society. Yet the labour theory of value, that Marx holds to display the exploitation in the market system, that consists of the extraction of surplus value from the workers, dominates the whole of the book. Indeed, one might think, in reading the book, that Marx had forgotten communism to defend what he later called “classical economics” against what he called “the vulgar economists” rather than to attack bourgeois economics, or even capitalism, as a whole, as was his expressed aim to begin with.

Most readers understand the book as a protest against surplus value, or the unpaid labour that is exploitation, but that is not the case. Indeed, many might hold that there is no existential import in the idea of surplus value; indeed, modern marginal theory holds exactly that. Some critics have made the point that land or capital could be taken as primitive and that the aristocrats or the merchants could be shown to be the exploited class in much the way that Marx had it that the workers were, and with the same level of achievement, or validity, and that seems to be so. But exploitation is not what Marx was objecting to, rather, it was to the lack of overall social control, or central planning. Value, price and profit would end in the new society and so would surplus value. We would not be exploited in quite the same way by the use of money, which would also fade away, but we would still be exploited. It never was exploitation, as such, that Marx rejected but the anarchy, or the lack of overall central planning, that he usually calls the conscious social control over society by the administration. He rejected what the bourgeois called freedom. He thought that the anarchy of the market leads to war and to economic slumps, but Marx had no full explanation either of wars or of slumps. The likes of Mises denied that slumps were intrinsic to the market, of course. The early Hayek of the 1930s thought they were but the later Hayek of the 1980s thought otherwise, as he then thought the privatisation of money might remove any possibility of slumps, which he thought rose from a government monopoly of the money supply.

As the market anarchy persisted in peace and in times when there was no slump, more than mere anarchy was needed to explain both problems But an adequate explanation of wars or slumps is not really in Marx's output. He did think that communism would remove both problems and, for a long time, Marx thought it would remove the disutility of labour too. Later he tended to doubt that, saying that shorter working hours for unpleasant tasks in society might compensate. No longer would surplus value be extracted from the workers by buying their labour power and then pushing them on to producing more than the cost paid out in wages for it, to thereby reap surplus value, or unpaid labour. Some surplus would still be taken in the new society. Marx implies, but rarely makes explicit, the fact that an employer could hire labour and fail to push it to produce more than it costs to hire, thus failing to get any surplus value, or exploitation, from it.

Not any old labour could give value to a commodity but only what Marx called “socially necessary labour”. This was labour applied at a pace and in a time that current working conditions on the market set. Clearly, a slow worker would not thereby create wares of greater value than one who produced more of the same quality output . But this idea was not quite consistent with Marx's aim of giving an objective alternative account to vulgar supply and demand, as current working conditions were set by that vulgar supply and demand. Marx seems never to have noticed that particular problem with his theory, though his reluctance to publish may have been owing to the fact that he did spot some problems with it.

Contrary to what some readers think, the labour theory of value is a theory that acknowledges that the market is a positive sum game. The haggling that is zero-sum, that alone makes up the actual class struggle for Marx, is within a pocket that is limited by mutual gains; within a positive sum game. Thus his sole example of the class struggle is self refuting; as it is an example of overall common interests. This, unwittingly it seems, effectively refutes the idea that the class interests in society are overall diametrically opposed. It holds that they are only so within a very confined range – that of the haggling process. The main common economic interests of both sides is to settle that haggling process. Marx saw the there were more outputs than inputs on the market, but he still thought there was a class struggle.

As with the demand that we have a society where we have production for needs or wants (as if we do not have one already), this class struggle meme has to be hyperbole that Marx himself refutes in his book. For he asserts that society is in production for use value explicitly and that there are common economic interests in positive sum wage bargaining too. We have only a pocket of zero sum haggling in an overall gain to both sides. Exploitation is held to go on nevertheless and this might lead many readers to conclude that there is real class struggle. But the book is not against exploitation, as a surplus of some kind will always be needed, This surplus may be even less clearly extracted in the new society than in the case of the mysterious market process, which Marx felt that only he had understood and explained. In any case, Marx thought the new money-less economics would eventually emerge from the giant firms rather than from the class struggle, as some readers imagine he just must hold.

Marx did tend to hold a subsistence theory of wages, not so unlike that of “the parson” Malthus, and he would most likely have accepted that he had been refuted by the actual and clear rise of real wages since his time. He had an increasing poverty meme, meaning a destitution meme, that later socialists converted into an increasing misery, or relative poverty meme. They thought that increasing envy against relative wealth might be what Marx held rather than the increasing destitution that he seems to have actually held; though he did deliberately obfuscate what he said by ambiguity. Nevertheless, his epigones’ later apology reads like the Jehovah's Witnesses maintaining that the word translated into English as “day” in the Bible really means “epoch, even though both Marx and the pristine Bible authors had no clear need for any such equivocation before the march of events made such a need all too clear.

Marx thought that the signs were, in the market society, of the acorn that might grow into a mighty oak, for there was, he thought, a tendency in society towards monopoly. In adopting the idea that competition lead to monopoly, Marx was adopting an idea that was popular before he was born and that remains popular today, but it is one that many empirically minded economists have seen to be false. Unless a monopoly is maintained coercively by the state, many liberals have thought that the market will be good enough to polycentrically and freely regulate large firms that will face the diseconomies of scale. Marx overlooked these and stressed economies of scale which he thought would never face any limit, as he thought the bigger the better in economic development. But many economists, like Sir Arnold Plant (1898-1978), held that a free monopoly was not very important as it did face eventual diseconomies of scale as well as facing free competition from other wares, as any good in monopoly production would have any number of substitutes or rival options on the market. They held that monopoly was not increasing and the facts seem to have borne that out since at least 1800, if not before then too. There is no build up of monopoly since Marx's day.

When the giant firms emerged that would exploit economies of scale, that Marx thought to be limitless, the firms would soon get too big to relate well to the money system, or the external market, in their internal economy; so they would remove themselves from the market to some degree. To that extent, they would need to have some new sort of internal economy to survive, a need that Marx thought they would soon satisfy by solving the economic problem in a new way, and later society, as a whole, might find this new economics useful to replace the price system with. The use of money would then soon wither away in large parts of the old society as the giant firms emerged.

The withering away of the state was not going to be anything like a withering away of the central administration, or indeed like the future use of money in society. On the contrary, scientific production was bound to be a central planning system, thought Marx, as he never got beyond the tyro assumption that planning was going to be way superior to the anarchy of the price system, an anarchy that he thought would be the downfall of the market system, sooner or later. But rather as all class conflict would end, the administration would no longer be a state in the new society. Marx's rivals, like Bakunin, thought that this would be a stronger state than ever, and current common sense would agree with them. Marx’s ideas on the state are very academic or scholastic.

The whole book, insofar as it remains socialist rather than a defence of classical economics against the vulgar economics, is basically a work of propaganda rather than of science. The hyperbole never, or hardly ever, is corrected by the details in the book on commodity production not being for use, when it only truly claims not directly for use. But, as propaganda, the book draws on the idea of science for sheer prestige, and thus Marx claimed to be a scientific rather than a utopian socialist. He considered the utopian socialists to be unscientific. But Engels took many basic ideas from Robert Owen, whom he later called “a utopian”, and Marx took many of his pristine basic ideas from Engels in the early 1840s.

Ironically, Owen tended to test his ideas in practise, at New Harmony and later in seeking a front for the bogus idea of the class struggle, which he clearly did not see as bogus, in his setting up of the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union in the 1830s. Marx preferred to work on his own in the British Museum and to write in a deliberately ambiguous fashion that could not clearly be tested. As testing is vital to science and being ambiguous is alien to it, Owen was nearer to being scientific than was Marx.

Whenever a socialist cannot adequately answer an objection to socialism he may well think that one of his wise comrades in Edinburgh will be able to do so, but even if the man in Edinburgh fails then maybe the answer will be somewhere in this very large book, or in the extended notes, produced by Marx. Like the Bible, that so many religious people imagine they might find actual answers in, what awaits the reader in the Marxist big book is a distraction that will aid him to forget the question rather than an answer to any problem of life, or to any real problem of socialism. Marx himself hopes that history will throw up answers that we cannot know beforehand, all rather similar to Popper’s thesis in The Poverty of Philosophy (1957). We cannot tell the future, ipso facto. But it will most likely display things that we do not now know. Marx and Popper might well agree on that, but Popper imagines it to be a point that he made against Marx.

Many readers of the first volume, or even of the four volumes and the later published notes, never notice that the class struggle and the labour theory of value that take up most of the four volumes of the book are not what Marx looks to as paving the way to the new society but rather that it is the tendency to giant firms to exploit the ever increasing economies of scale that he put his hopes in. When the labour theory of value was refuted in the 1870s, by the marginal revolution, this destroyed Marx’s theory of exploitation but it did not affect the idea of the slow development of the new society that Marx thought was progressing in the womb of the old one.

The End of Marx

Marx rightly thought that private property and the price system could never be

planned overall. Money was intrinsically anarchic, so it would mess up any

central plan. As it was anarchic, he thought, that the market was intrinsically

inefficient and so not sustainable in the long run. But it was not that Marx thought the

market used up too many resources, as the Greens today hold, but rather the contrary,

that it prevented the even more rapid economic growth that planning could achieve. He felt that only central planning and the use of the latest science could achieve this. As science too, is somewhat polycentric, or anarchic, this was another thing Marx seemed to overlook. He had the bogus idea that the market would keep wages at subsistence levels, but like the Second Coming that is now 2000 years, or so, overdue, and is not truly held today by any Christian, despite any lip service paid to it, this destitution meme of pristine Marxism is an idea that not even the most devoted Marxist can today truly credit. The relative poverty apology is a scholastic one but it allows them to overlook that their creed is now very clearly out of date – a fact that might have been plain to a diligent reader of Marx's book way before 1900.

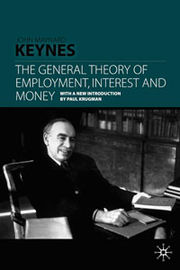

7) General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936)

John Maynard Keynes

This book pushes some very silly ideas, but, again, the author was not really a wicked man. As I repeat below, he was way nearer to being simply a silly man.

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) was a member of the British elite. He was educated at Eton public school and later at the University of Cambridge. His father, John Neville Keynes, was a logician and an economist who survived Maynard by about three years. He got his son to study under Alfred Marshall for an academic term. Maynard had a deep anti-bourgeois outlook from his teens onward that he never lost, despite having an equal antipathy to Marxism later on.

I repeat, Keynes was nearer to being a silly man than to being an evil man but the ideas he pushed were very wasteful, as is internecine politics generally. It is odd that at the end of his 1936 book he begins writing as if he had no idea of economics at all, saying that scarcity would soon end, and the like.

With this book’s dominant legacy, we face the problem of “mindset”, where people tend to see what they expect to see. Keynes’s “revolution” made a bias towards his outlook that effectively places his forerunners out of court. But note that this idea of mindset is quite distinct from seeing what we want to see, which is not humanly possible at all, for we always see what seems to us to be the case. Mindset explains the book's great success but also the survival of the author's naivety throughout the many textbooks of economics that he did read. Wide reading of books was something he had in common with Marx. Many critics of his work say that Keynes never read much, but his writings seem to indicate quite a lot of reading. Marx was much the same in failing to fully comprehend some basic ideas. Marx never did see that planning was inefficient and Keynes failed to realise that scarcity was here to stay. Odd, because he often writes against Marxism as if he does know basic economics but then he comes out with the end of scarcity memes at the end of his book that clearly show that he was muddled on and even ignorant basic economics.

One of the more clearly silly ideas of Keynes was his interpretation of the ethics of George Edward Moore as a doctrine of immorality, a doctrine not far off from being an absurdity, ipso facto, as to advocate a doctrine in ethics is to recommend it as moral. Immoralism was an outlook celebrated in Keynes youth but he repeated the celebration of it throughout his life without realising it was merely absurd or silly. This immoralism was sheer hyperbole from Keynes, of course. He would not be indifferent to murder, though the courts today almost are and they do not have the benefit of Moore. One example would be the case of Dean Ingram getting only three years and a few months for killing Lawrence McCourt in 2008. It was bogusly claimed as manslaughter and the murderer saw no reason to cover up his contempt for the courts. He is almost bound to kill again in a few years time. Keynes was not one whit amoral, or seriously immoral, in actual life, but he merely played around with the idea of being so. As said above, he was a silly rather than an immoral man. The anti-bourgeois, anti-Victorian claptrap developed in the Bloomsbury set was fine for a private group of eccentrics but as a public outlook it was silly and Keynes was merely being silly to endorse it throughout his life to the extent that he did, but few seen him as such.

Mark Blaug once retorted to Keynes’ statement that Ricardo had conquered England to a greater extent than the Spanish Inquisition conquered Spain by saying that Keynes had conquered the economics profession even more successfully than Ricardo ever did. Certainly, after 1936 the younger economists adopted his outlook about as much as they possibility could, and they only failed to follow Keynes when they could not really comprehend his ideas. He won most of the economists over about as much as people could be won over. He has ever since been claimed as the economist of the twentieth century by most economists, including Milton Friedman.

Why did the Keynesian memes, or objective ideas, win out and how did they survive their rather clear refutation by the occurrence of stagflation during the 1970s?

That is, the main problem I intend to consider below, but note that false theories are rather like human lives, in that they may be very vulnerable to diseases at the infant stage, but once that is over, they can withstand attacks quite well up till old age when they once again seem to have weak defences. Similarly, false theories may not gain currency at all when they are first formed, but once a theory becomes popular, mere common sense objections will not matter much in science, or in wider academic study. It will be put down to mere ignorance. This quasi-privilege against common sense is a major reason why Keynes’ theory survived the refutation of stagflation in the 1970s but it was also so well embedded in the textbooks and in the economics profession. Such objections become very potent, again, when the theory is on the decline, which can happen as a result a change in fashion, or if it is seen as being refuted by a rival paradigm, or by the external facts – which is rather like a fatal accident.

Free, or at least freer, trade and state management or protectionism are often contrasted, with the latter often called socialism. Keynes favours management, but never socialism, though his ideas were to a large extent shared with people like G.B. Shaw, who thought of himself as a socialist. Keynes preferred state management rather than the free market and thus belonged to the Radical-Joe-Chamberlain tradition of liberalism as opposed to that of the classical liberals, who ebbed after Gladstone. But this means that for Keynes, as for Marx, it is really the lack of management or overall planning on the market that tends to irritate, rather than mass poverty, the problem of war, [Marx’s concern] mass unemployment [the concern of Marx and Keynes] that others thought were their main concern, though they did think they had solutions to those problems. Keynes feels that the elite, the politicians, and others, have something to offer and he does not like the way economics has tended to be hostile towards politics, or the civil service that he went into as a main career and this may be why he admired the civil service. He certainly had some contempt for businessmen. But it is not the case that the economists ever particularly eulogised the businessmen, though Marshall did think that economics might help them and he did show them some special concern. Maybe that is what Keynes reacted to. He feels there should be some inequality in pay, but not much, and certainly not to the extent common in his own day. He admires the slow growth of taxation to curb the differences in income.

On the first page of the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936), Keynes’s main book, and the book I set out to criticise, the author, oddly, openly confesses to “a solecism” (p3) but, instead of correcting it, he leaves it in the text. Has he set out to scotch grammar? That would be a very odd thing for any author to deliberately do. This solecism is (p3) that he sees the classical economists, not as Marx saw them, [viz. the authors who upheld the labour theory of value as against the ones who thought that supply and demand were enough. Marx called the latter “the vulgar economists” as they settled for surface appearance rather than going to deep reality, which Marx took to be the proper job of any science] but way more inclusive. Keynes sees the classical economists as being all the earlier economists. Many of those lived up to forty years after Keynes died [e.g. Hayek died in 1992, but Keynes in 1946].

The reader might realise that this is not a solecism at all, but an anachronism, i.e. an error of history rather than of grammar. The reader still might think it mighty odd that the author sees an error of any kind, but still leaves it in. But is it an error of any kind? After all, Plato seems to have been quite right when he says that no one can deliberately err. Is it not, rather, a clever and deliberate ploy that Keynes is here using, a device similar to the use that Nelson made of his blind eye? He is going to use this “solecism” device to pretend to see only what he wants to see. But no one can ever quite do that, if they remain sane.

Richard Whately

Here we can see what sort of an author we are dealing with in Keynes. Richard Whately once said that “it makes all the difference in the world whether a man puts the truth in the first place or in the second place” and Keynes openly puts the truth in the service of his aims, and he aims to be revolutionary in theory even if he wants to remain Fabian and gradual in practice. But this “revolutionary” ploy does not mean that Keynes was insincere in what he wanted to say, but only that he was impatient to say it and that he also sought to dismiss the opposition; permanently.

The pristine classics were thrown out by “the Marginal Revolution”, which took place in the 1870s, when marginal theory replaced the labour theory of value cost of production paradigm. A few “vulgar economists”, Jevons, Menger and Walras, applied Ockham’s razor to the labour theory of value and marginal theory dispensed with the underlying reality. Keynes lets us know that he is to make a new revolution against those he terms “the classics” and he hopes it will be as complete as the one in the 1870s was. That revolution replaced the cost of production theories with marginal theory that Jevons explains thus:

“We must now carefully discriminate between the total utility arising from any commodity and the utility attaching to any portion of it. Thus the total utility of the food we eat consists in maintaining life, and may be considered as infinitely great; but if we were to subtract a tenth part from what we eat daily, our loss would be but slight. We should certainly not lose a tenth part of the whole utility of food to us. It might be doubted whether we should suffer any harm at all.

Let us imagine the whole quantity of food which a person consumes on an average during twenty-four hours to be divided into ten equal parts. If his food be reduced by the last part, he will suffer but little; if a second part be deficient, he will feel the want distinctly; the subtraction of the third part will be decidedly injurious; with every subsequent subtraction of a tenth part his sufferings will be more and more serious, until at length he will be on the verge of starvation. Now, if we call each of the tenth parts an increment, the meaning of those facts is that each increment of food is less necessary, or possesses less utility, than the previous one.”

The later idea of opportunity cost, that costs are best seen as current foregone options, especially the best alternative, rather that what we have put into one of the options hitherto, went further to highlight the fallacy of sunk costs that the classical pre-1870s theory tended to foster. From 1880 on the old paradigm was quite defunct.

It is fairly clear from reading the book that Keynes is largely attacking only one author, Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877-1959), and only others economists in so far as they agree with Pigou, so he has no need for an anachronism at all to do that. But Keynes clearly wants to say it is “the classics” that he rejects – he wants a revolution in theory to render his variously differing forerunners utterly defunct. And what he says, even of Pigou, ignores many things that Pigou says, even in the main book, The Theory of Unemployment (1933), that Keynes, cites in this 1936 book. Pigou repeatedly mentions the term “involuntary unemployment” in that 1933 book, for example, but Keynes, repeatedly, says that none before him even thought of that concept.

Arthur Cecil Pigou

Many authors conclude that Keynes had not read much, owing to him saying that “the classics” did not say this, or did not say that; when they so very clearly did. My guess is that he was quite well read in economics; even though he had values that were always in complete opposition to what he saw as the anarchy that the economists, usually unwittingly, embraced. He rightly saw that economics was largely biased against politics and state planning. Marx, with the same objection, set out to be not only a hostile critic of economics, but also to be a revolutionary; to replace the market with moneyless communism. Keynes thought that money was vital and he was content with political demand management by means of inflation. He rather hoped that most of bourgeois society would go on much as before, but now with the civil servants taking the place of the capitalist class in organising savings by taxation and so dealing with the problem of investment, whilst unemployment might be cured by the stimulus of extra money in demand management. His epigones, in true Tory hyperbole, claimed that he saved the market from the Marxist threat, a brutum fulmen if ever there was one, rather like the imaginary wrath of God.

In any case, inflation is not really a stimulus, no more than is alcohol, though both may feel like it, for one depresses the nervous system whilst the other destroys the power of money to relate to the real economy thus, ironically, destroying effective demand and thus effectiveness overall.

![]() Only increased output can increase aggregate demand and increased saving is a prerequisite of investment that is the major cause of increased growth, or output, rather than it detracting from demand, as the absurd paradox of saving holds. This money stimulus idea is the main fault in the Keynesian outlook; the main idea about money is false.

Only increased output can increase aggregate demand and increased saving is a prerequisite of investment that is the major cause of increased growth, or output, rather than it detracting from demand, as the absurd paradox of saving holds. This money stimulus idea is the main fault in the Keynesian outlook; the main idea about money is false.

Only increased output can increase aggregate demand and increased saving is a prerequisite of investment that is the major cause of increased growth, or output, rather than it detracting from demand, as the absurd paradox of saving holds. This money stimulus idea is the main fault in the Keynesian outlook; the main idea about money is false.

The ploy worked as persuasion, even if there never was any viable new economics for it to innovate. Almost the whole of economics adopted the results of this “solecism” after 1936. This was “the Keynesian Revolution”. Keynes did develop new terms in the theory of demand management, though little of the substance was unknown in the 150 years before Keynes, even if he gave it a modern guise. But Keynes thought his forerunners, like Malthus, were misunderstood. But J. B. Say seems to have understood Malthus better than Keynes ever did.

Sir John Hicks

Oddly, the result in the textbooks fell out of Keynes’ hands and retained a few ideas he most hated, like equilibrium, as it owed almost as much to John Hicks, and others, many of whom did not fully comprehend Keynes.

Using his “solecism” ploy, Keynes said that the classics had no idea of the possibility of mass unemployment owing to Say’s Law, itself also redefined by Keynes. He described Say's Law as maintaining that there was nothing for the entrepreneur to do, as supply exactly created its own demand automatically rather than merely boosting general demand with the coordination problem being the task of the entrepreneur, as Say, and most others before 1936, had it. Keynes also held that David Ricardo certainly had no knowledge of trade cycles, or of mass unemployment. Every economist after 1936, or very nearly everyone, took all this as the gospel truth, which it ironically was, for the Christian gospels also were more concerned with the message than with the truth, and they too were mere make-believe. But their adherents were sincere, or at least convinced.

An illustration of the “mind set” that resulted after 1936 is shown by Thomas Sowell in Black Education: Myth and Tragedies (1972). Sowell had copies of Robert Heilbroner’s The Worldly Philosophers (1953), one of the many economists who adopted most, if not all, of the Keynesian outlook, on every desk, opened where Heilbroner says that Ricardo says nothing about the trade cycle, together with Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817) opened on the page where Ricardo begins his discussion of that topic. Sowell asked the class to read a bit of both books before asking them if what Heilbroner said about Ricardo was true. To his astonishment, they all replied that what Heilbroner said was true. When Sowell, flabbergasted, asked them why, he was told, in reply, that Heilbroner would not have written so if it is was not indeed the case.

David Ricardo

I will say a bit about the myth of “revolution” in general. The word “revolution” is today a bit of romance jargon, and Keynes realised this, but he felt a dire need to make “the classics” defunct. He saw economic theory as part of the problem, not only of mass unemployment but also of the barbaric anarchy of modern times. Keynes knew there could be no actual fresh beginning, but something like one seemed to be needed. “Revolution” is actually just empty jargon, a constituted blank, which is often imposed on an account of the facts by the historians. When the vicar finds out that a couple indulges in sex before marriage he feels he has discovered yet another instance of sin, but the idea that it is a sin is part of his ideology rather than the facts he has discovered about the couple in question.

The jargon word “revolution” clearly has a history and it was first used by the Whigs in 1688. It was taken from geometry, and it was, back then, used in the exact opposite of how it was used in 1789 by the Romantics and as how it is still largely used today. It was used to mean a return to the beginning of the drawing of a circle, to complete the revolution, and this meant exactly the same as “reactionary”, a reaction against recent innovation and an attempted return to the status quo ante. The idea was that James II had gone one half of a revolution away from how things should be, and that they needed to go back to how things were before he reigned. But in 1789 in France, the idea emerged with the new meaning being more like going off on a tangent than in completing the revolution, for it introduced the current meaning of going on to a new epoch and leaving the past completely behind. But Keynes was right to think that gradualism was the case and that no event makes for a completely new beginning. At least he got one idea right.

As if to show that getting something right was no fluke, Keynes ended his book with an attack on the then, and even still today, current common sense, cynical in the vulgar sense, outlook that ideals do not matter but that vested interests do. He writes:

“At the present moment people are unusually expectant of a more fundamental diagnosis; more particularly ready to receive it; eager to try it out, if it should be even plausible. But apart from this contemporary mood, the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back. I am sure that the power of vested interests is vastly exaggerated compared with the gradual encroachment of ideas. Not, indeed, immediately, but after a certain interval; for in the field of economic and political philosophy there are not many who are influenced by new theories after they are twenty-five or thirty years of age, so that the ideas which civil servants and politicians and even agitators apply to current events are not likely to be the newest. But, soon or late, it is ideas, not vested interests, which are dangerous for good or evil.”

It is hyperbole, of course, but the basic message is correct, vulgar cynicism is way overrated. That we learn nothing much after 30 is rarely the case. The closed mind is as much of a myth as the open mind. We all have biased minds. However, ideas, renamed ‘memes’ by Richard Dawkins, do have an affect on many who tend to over look the impact of them; though Dawkins errs badly in thinking that they are not at risk from criticism. But even though Keynes got the odd idea right, the book is full of paradoxes in the sense that cannot adequately be rescued by further explanation or experience, as they are intrinsically absurd.

8) Philosophical Investigations (1953) Ludwig Wittgenstein

Wittgenstein is widely celebrated as the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century, but the book that most look to as showing this to be the case is exceedingly silly, if not even remotely evil. It is, maybe, the worst book that has been celebrated as being a very good book in philosophy so far. Like his friend John Maynard Keynes, Ludwig was merely a silly man rather than an evil one.

But we ought to note that the author never did see this book as fit for the press so it is not a book that he did think was ready to be published. However, it was not likely to get much better, had the author lived far longer than he did. But, maybe, he would never have published it in any state that it ever reached. The one book he did publish is short, but quite good.

The posthumous book reads like a soliloquy or a conversation that the author has with himself. This is a language game that the author uses to introduce many other language games, an idea that seems to have influenced the psychiatrist Eric Berne, who way later wrote The Games People Play (1964). The general idea was that people did not always use words literally, but the author also, sometimes, hints that a literal interpretation might throw light on the discourse; though his more usual castigation is against the likes of debunkers, like James George Frazer (1854-1941) whom he thought took religion too literally when it demanded a Politically Correct sympathy, plenty of respect and tolerance. The main game of the author was to use his authority to deflate those he criticised, by claiming that they openly abused, or were unwittingly fooled by, language. The book is an anti-philosophy book, just as the 1936 book by Keynes is against economics, but, as we cannot truly get outside philosophy, so this anti-philosopher was held to be himself a philosopher and a very skilful philosopher at that. Like Keynes, he was ironically adopted as the best in the world at that which he set out to attack.

The author set out to show that philosophy is a sort of mental illness, or at least a sham, that is best avoided, or given up if it is ever begun. The author was out to show that philosophy was largely a meaningless muddle that arose from a misunderstanding of the normal use of language; that usually required a context to work well.

This central thesis turned a blind eye to the fact that philosophy was the forerunner of nearly all modern sciences. They all broke away from philosophy, usually as they adopted modern mathematics and the modern experiments that were developed along the way and tended toward both specialisation and team-work. But Wittgenstein was out to put science in its place too. Science was not able to explain a great deal in life, that philosophy and religion vainly continued to try to make sense of, but could not explain either. Many of those things simply could not be explained at all. Much of traditional metaphysics were quasi-mazes, or the equivalent of a fly getting stuck in a bottle where thereafter he is going to continue to be puzzled by the glass until he flies out of the neck that entrapped him. Clearly, the fly should never have flown inside the bottle in the first place. Those who go into philosophy will be going into a similar dead end. Philosophical problems like those of free will and determinism, or what it is to be beautiful, or what truth is and the like, are all mere folly and to try to solve them as though they were mundane true problems is as futile as the fly trying to fly though the glass side of the bottle he has wandered into. They arise from a mere misunderstanding of normal language and its relation to its normal context. Metaphysics and other branches of philosophy drift off free of any context but context is a prerequisite of language. There are no essential meanings of words but only a usage developed in a context.

The normal use of language in society does not cause such problems, as normal usage is usually adequate to get by on within the social context it developed in. According to the author, it is only when a few academic fools, called philosophers, pretend to be clever that crass confusion arises.

Language needs the context of social activity to work nominally but the philosopher tends to unwittingly shed all such practical context as he goes abstract. Here Wittgenstein is a bit like Lord Francis Bacon on the false idols where ideas become impractical ends rather than normal instrumental communication, or problem solving means. Both, similarly, call for a return to the mundane everyday life as the solution to mere metaphysical impractical time-wasting.

Ironically, the whole book is rather like a bottle for the attacked philosophers to get bewildered in. Most readers overlook that it is written in fairly simple language, as they feel it must be more profound then it clearly is. They persuade themselves that it is difficult, but the only oddity to get used to is that it is a soliloquy setting out to do the work of a dialogue, for the author takes many parts and he jumps from one position to another without announcing any change. He introduced straw man after straw man, that none seem to have ever known of before, but that fans of the book imagine are not straw men at all but actually apply to this or that earlier philosopher, but that is not really the case in any earlier philosopher at all. However, one later philosopher did adopt the idea of a private language, thus rescuing one straw man, for A.J. Ayer adopted the idea in the wake of discovering it in the book. That was a mistake on Ayer's part, for it is quite true that there cannot be a private language in the sense that the author meant it. As the author rightly held, if others cannot comprehend what we say, our later selves will not be able to do so either. Wittgenstein begins his case against private language at paragraph 269 about sounds or speech that we may hear but, typically, a few sentences later in the next paragraph he is on about the written word where he says that we may put “S” in a diary to privately relate to blood pressure but it will not relate at all to the actual physical condition, so it is a mere show to write “S” whilst looking into oneself whilst thinking of blood pressure.

But no one before Ayer ever did hold to a private language; and he only wanted to do so in order to oppose the author. He was about the only one who adopted any one of the many straw men and he did so to merely opposite the criticism of it. However, most of the rising generation felt the new ideas were not straw men at all, but wonderful insights.

The book is on par with the one by Keynes in opposing the field it enters, being as anti-philosophy as Keynes’s book was anti-economics. Both books ironically earned each author the position of going to the top of the profession they set out to attack by presenting a series of seemingly bogus ideas that were taken up by the rising generation to be utterly brilliant.

9) The Catechism of the Revolutionary (1869) Sergey Nechayev

Sergey Nechayev

The opening lines are:

“The revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no personal interests, no affairs, no sentiments, attachments, property, not even a name of his own. Everything in him is absorbed by one exclusive interest, one thought, one passion – the revolution.”

He has no joy beyond sacrifice to this perverse descructive quest and his duty is to get others to similarly sacrifice themselves to it in the same mindless way.

The imagined revolution was sheer romance as there was nothing one whit realistic about it, not could there be. But the jackass Machiavelli did have an entity to sacrifice to. The state really exists, and that may be one reason why Machiavelli was more evil than this silly epigone, Nechayev. They had in common that to sacrifice one's values to a perverse anti-social end was somehow worthy.

Maybe this is the main text that influenced Lenin to take the moves away from Marxism that he began in his What Is To Be Done (1903), a book that just missed out from being included here. We might imagine that it is responsible for all the perverse mayhem produced by those it influenced. If so, then the silly little pamphlet of Nechayev is, maybe, worse than all of Lenin’s books and Nechayev himself is worse than Lenin or his epigones Stalin and Trotsky in being more direct. It is plain enough that he never achieved so much in bloodthirsty killing. He was, clearly, influenced by that essay in pure politics, The Prince (1513) by Machiavelli but he writes in an even shorter compass. He adopts the idea that the end justifies the means from the earlier book. All that matters to both Machiavelli and Nechayev is the perverse domain of politics. The author says that a revolutionary

"must infiltrate all social formations including the police. He must exploit rich and influential people, subordinating them to himself. He must aggravate the miseries of the common people, so as to exhaust their patience and incite them to rebel. And, finally, he must ally himself with the savage world of the violent criminal, the only true revolutionary in Russia".

It not only influenced Lenin and his followers who reached that acme in Mao but also petty groups like the Black Panthers who republished the pamphlet in 1969. Terrorist groups, like the Red Brigade of Italy, also saw it as worthy.

Nechayev pushed his silly boyfriend, Bakunin, into ever more misanthropic hyperbole. Dostoevsky wrote a novel based on Nechayev that he called the Devils or The Possessed (1872). He displayed therein the barren and silly nature of such fools, as did Conrad in The Secret Agent (1907), that showed what the more normal epigone can do by default. The normal “anarchist” of this statist type [they usually call themselves left and support political redistribution schemes as well as state schooling and the UK's NHS] is a sort of play-acting that might recoil from real evil. When Nechayev had a student, Ivanov, murdered in Russia, Bakunin disowned him, showing that he was more normal than his former friend. He denounced him as adopting the Jesuit motto of “Violence for the Body; lies for the Soul”. But Nechayev was merely taking the daft ideas of Bakunin seriously and revising them to be that bit more extreme.

As a eulogy of perverse romantic terrorism, this book – well pamphlet – is the pits.

10) The Female Eunuch (1971)

Germaine Greer

I do not suppose for a moment that poor old Germaine Greer is evil in any way but she did write a silly book full of silly ideas. The background of Malthus and the over-population meme is a big reason why the many silly ideas of this silly book caught on. It soon had women setting out to behave as if they were men and this caused the celebrated actress, Dame Edith Evans, to proclaim: “When a woman behaves like a man why doesn't she behave like a nice man?”

Like gay rights, Feminism has two sides: 1) a protest over genuine injustice where there has been victimisation by the state robbing women and homosexuals of basic civil liberties, so this protest is one that chimes in perfectly with the classical liberal outlook; 2) A totalitarian Political Correctness [PC] that calls for conformity to sheer absurdities involved in the ideal of equality that the PC mantras repeat absurdly and endlessly to be enacted, not least in the campaign against the common sense outlook of the 1950s.

Then we have the PC comedians in the so called alternative comedy movement which, as Bob Monkhouse spotted, is actually an alternative to, and an intolerant censure of, comedy, where the likes of Stephen Fry and Jo Brand spin out their dour PC claptrap as if it was said in jest and was also was the acme of wisdom instead of the impossiblist dogma that it is. Ms Greer seems to be in this crass PC school.

One silly idea was that men hate women but they do not realise it! No doubt the authoress feels that oxymorons like the unconscious mind can save her oxymoronic content in the text as well as in the title. But the mundane truth is that we need to feel hate to hate.

Another silly idea was that women were oppressed in the consumer society in their suburban homes when they looked after their nuclear family, but few ever were. It remains the normal aim today, and it will most likely be so in a hundred years time too.

It was silly to say that men made the culture of the housewife as women have always done more of the socialisation of the both sexes of children compared to men. Peers maybe do more to socialise each other than do adult women but men have never had much of a look in by comparison; a thing that Feminism moaned about, so that it should have realised to be the case. So the idea that they, sort of, castrated the females, in some way, is silly in all sorts of ways.

Trust the utterly unrealistic authoress to reject evolution for the romantic meme of revolution. But her adoption of it fits the rest of what she had to say in the book and it is all fairly clearly false.

![]()

Top 50 books of all time : by Old Hickory:-

"I have limited the selection to the books I have read. I keep to the norm of not recommending to others books I have yet to read. Clearly, books I have not read by now suggests a judgement of some sort."

The Alternative

Bookshop

Which specialises in,

but does not limit itself

to, books on Liberty

and Freedom ... Book

reviews, links,

bestsellers, rareties,

second— hand,

best price on books,

find rare books.