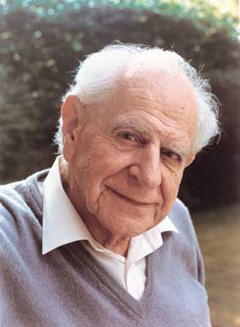

The Myth of the Closed Mind:

![]()

Understanding Why and How People Are Rational by Ray Scott Percival. Open Court: $34 97.

Here is a good book on our biased, erring minds and our dire need to spot, and thus to eliminate, our errors. It might even become a classic.

This book rightly repudiates the idea of irrationality, as did a few forerunners like The Myth of Irrationality (1993) John McCrone and The Passions (1976) Robert C. Solomon, to cite but two earlier books that suggested a similar thesis. However, this latest book is more cogent and consistent than those two earlier books.

Shakespeare was right when he made Hamlet say to Horatio that there were more things in heaven and earth than were dreamt of in his philosophy, as we still do not know how many things there are in the world. We expect to discover fresh species or even a phylum in the future. It is all too often the case that there are many ideas in philosophy, or even in common sense, that seem to refer to nothing at all in the external world. So we more often need to inform people that there is less in the world than in their philosophies.

This is so concerning the mind too, as many ideas about mental phenomena are very popular but they seem to be quite false: faith, the closed mind, prejudice, the open mind, self deception, the unconscious mind, and the idea that we can believe whatever we like are just seven popular ideas that current common sense holds to be factual but seem to refer to nothing that is real. The idea that humans are irrational seems to be the core meme that fosters the seven cited false ideas. The particular idea Professor Percival sets out to refute here is that of the closed mind. He rightly says there is no closed mind, but there is no open mind either, as we all have only the biased, erring, human mind. We all make assumptions that are either true or false. The duty we all have is to test the assumptions as well as we can. We all need to eliminate any error that one of our biased assumptions may introduce.

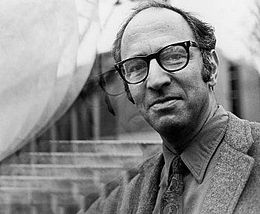

The hero of this book is Karl Popper

The hero of the author's account is Karl Popper, who realised that we all make conjectures that might be false as well as true. He held that we thereby have the duty of attempting to refute our own pet ideas. Michael Polanyi reacted that this idea of Popper's was quite perverse. However, as we might be wrong in any assumption, Popper seems to be right that it is a duty that we all have, even if it does seem an odd thing for anyone to attempt to do.

Debate is one way of getting others to assist us in this odd Popperian duty, for that is a way to put the task onto the division of labour where we might get someone, who might see our errors more clearly than we do, to point them out to us; and then we might return the service by pointing any errors of his that we spot. That might seem less perverse. Whatever the individual motivation on each side in any debate, all debate is institutionally, at the society rather than the personal level, a case of mutual aid. As such, it is a social boon but because people look on eristic point scoring as driven by personal ill will, it is often classed as anti-social.

The author rightly says that common sense errs in holding that we can think as we like. We experience whatever we do experience naturally but can say whatever we want to. “We cannot decide to be unmoved by the validity of an argument that we grasp. As Plato put it, we cannot knowingly accept error (if we think it's error, then we are not accepting it)” (p.3). This means that Popper's conjecture of how science should proceed is naturalistically, if only tacitly and merely subjectively, fixed in the mind, as the checking up on whatever we think by our five senses is going to thereby revise any automatic belief-set, or panoramic belief-take, which we may have. What Popper recommended that we adopt objectively in science was always there subjectively in the natural working of our mind. However, it does need to be made objective to do science with. It is the subjectivity of belief that Popper rightly wanted to reject in his philosophy of science.

It is not clear that Popper would have welcomed that thesis, for he liked the idea that we should choose reason. He rejected naturalistic philosophy and most of all he rejected belief as irrelevant to the truth. Popper loved explicit objectivity, open to public testing rather than the tacit subjectivity of the mind that is way more nebulous. Belief was no criterion of the truth but merely what we thought was the truth at the moment. It could be true but it could be false too. He seemed to overlook that the same is also the case with conjectures but he stressed that the latter can be way easier to test publicly, as we can make them objective by writing them down.

It seems a bit churlish of Popper to overlook the fact that belief might be a good heuristic, a good source of fresh conjectures, but he maybe did so by default, as he was always far keener on the philosophy of science and objectivity rather than on the subjective philosophy of mind; he was far keener on sociological matters rather than on psychological matters.

However, Popper does put great stress on honesty and that ironically brings belief slap bang into his non-naturalistic chosen method. We can only say anything we like if we are willing to be dishonest. Popper holds that being dishonest is to be irrational. Lying is certainly an odd thing to do in enquiry. There would seem to be no coherent motivation for it. Yet it is very commonly supposed to go on.

The automatic flux in the nature of belief ensures that we are all open to criticism, though the fact that our mind is biased may obfuscate our understanding of many points, as may a lack of training. Many people, maybe most people, may feel simply unable to evaluate the truth in the global warming paradigm for example, owing to a lack of background knowledge. Any candidate proof that God does not exist is going to look barren to any emotional Christian propagandist but, as Popper so often says, psychology tends to follow logic. We will understand the syntax way before we see the semantics or will need to listen to or read what is said before we reach an adequate understanding of many theories. What looks cold, barren or simply empty today may well look exciting in six months time. In any case, we cannot control our own understanding of any criticism that is put to us. We can say what we like, but we can never quite think as we like.

The author holds that evolution is an open random process rather than a main broad road of progress where humans, or something similar, were bound to emerge. Indeed, he holds that it is almost a sure thing that humans would not emerge. “If you ran evolution again, you would not get anything like Homo sapiens ” (p.3). But the rational component may well emerge again, even if it were not linked to bipeds next time round.

The author puts the case for the closed mind (p.4ff) as a prelude to testing it. Many think that the emotions are beyond reason. There seems to have been a movement away from that idea towards seeing the emotions as vital to reason since the 1960s, but the Stoics saw that emotions were not separate from reason over two thousand years ago. This is well known to the author, who holds that the Stoics were basically right (p.4).

We tend to value rather than to believe the creeds that we adopt. As Whatley said: “It makes all the difference in the world whether we put the truth in the first place or in the second place” and for many who adopt a creed the truth is taken for granted as the object of the group is not to make any sort of enquiry but to indulge in the fellowship of the creed. This is why, with many creeds, the facts do not matter and why many hold the basic ideas as dogmas, i.e. as sacred ends rather than the mere means to seeing what reality is like. Many Christians do not care whether Jesus ever existed, or at least that is what they often tend to say on the matter. In listening to Christians express such ideas I have often thought that if one of them were to read one of G.A. Wells books and thereby become convinced of Jesus as a mere mythical character, he might well feel that it does matter. It does not seem to matter to any one of them as Christians today as they have no tangible reason to doubt that Jesus existed. They value the creed more than they believe it. However, it will need a factual basis even if that is less important than the values. So religion is not immediately concerned with the facts, or the truth, as the religious adherents tend to take the basic facts for granted.

A major idea that the author has throughout the book is that when we attempt to propagate a creed we thereby risk refutation. This is more or less known to the religious people, who therefore often seek to propagate unquestioned dogmas but there is no way that they can dodge that risk completely. Nevertheless, it is still a risk that many of the religious adherents want to dodge. So they do attempt to limit criticism very often. The major thesis of the book is that this is basically futile.

At no time do we normally refrain from using our five senses to check up on what we believe or what we think more generally. No matter how familiar we are, say, with our bedroom, we never fail to monitor what we are doing when we get dressed each morning. The fresh information we obtain from our senses rarely tells us much that is new but it is always worthwhile to check. We never go to the local shop with our eyes closed, no matter how well we know the way there. We feel we need to create fresh beliefs to see that the way ahead is right, safe, in short, how it was earlier. So our practical beliefs last no longer than the fresh air that we breath in and our belief needs to be renewed as often as we need more air, for we spend our beliefs in action just as we spend the intake of air that we breathe by refreshing our blood supply. Fresh air is needed for the body to function just as a fresh belief is needed for the person to do something.

The author says: “Tens of thousands believe in UFOs, spoon-bending, astrology, and so forth (p.25). But is this thinking the ideas true rather than finding them refreshing, entertaining or imaginary in a stimulating or playful sense? We do not criticise a horror movie we go to see, as we expect it not to be true. We choose to go to see it even if we are sure it is false. How people play around with the ideas of UFOs looks more like entertainment than enquiry to me. People are free to say what they like but not to believe as they like. Most people are not very clear on the belief/value distinction; indeed even some philosophers are not. So what people say does not always report accurately what they believe, as, in normal English, the word “belief” often refers to value or to what the speaker merely likes. There are any number of reasons why we might expect people to like UFOs but few as to why anyone should think that they exist.

A bent spoon

The author writes: “I fully accept that one can specify rules which if scrupulously followed would make an ideology unresponsive to argument” (p.32) but any such rules would require choice in what we believe. Indeed, the author has said to me that he does not think this sort of ploy can work if we are honest. Belief is way more like naïve falsificationism than the other end of the ideas in the history of critical rationalism that Imre Lakatos thought up and that Popper himself gave too much credit to, perhaps because he overlooked the actual nature of belief.

It is a misreading to think that falsificationism treats a candidate falsification as permanent rather than merely conjectural. Critical rationalism holds that refutations are as conjectural as confirmations, but that refutations are methodologically easier to manage and usually more likely to be germane or to the point than confirmations are. Like belief, falsification will allow earlier dismissed ideas to get fresh credit, if they looks to be true after all. A refutation is a temporary removal of credit rather than a death of the meme. This means that natural selection does not work as well in the philosophy of science as in does in biology. Popper's three worlds are W1 [the physical world], W2 [mind] and W3 [culture]. Popper attempted to apply Darwin's natural selection to objective ideas or memes. In the wild, individual animals or plants will be selected out as food such that populations could become extinct if all members are selected out. The law of the jungle is way harsher than anything in civilisation. With ideas we tend to get many generalisations rather than individuals and no idea quite dies out but rather only loses credit. It loses out only in the reader's mind rather than being selected out of any test. A refuted idea in a book only lacks credit in the minds of readers who see it as false. It may go on to be very effective with people who overlook the fact that it is false, if indeed it is false. So Popper's famous line that we can let our ideas die in our stead is unrealistic hyperbole; though it is entertaining and also rightly indicates that the fallacy of ad hominem is something that should be dodged.

In the same paragraph, but on the next page the author tells us: “After all if the critic becomes a believer he is no longer a critic. Similarly, if an extreme follower of Geog Lukacs always insists that his critics cannot understand the proletarian point of view until they join the struggle, then (providing that is all he does) his position is secure against criticism” (p.33). But this looks very unrealistic for many reasons, not least that there never was any Marxist class struggle; nor anything even remotely like it. What Marx called the working class, or the proletariat, never did have anything like common objective class interests, as Marx asserted. Moreover, we cannot control what we see as true; not in any case at all. No external organisation, party or creed can aid us in any futile attempt that we may want to make. The rapid conjecture and refutation process of ordinary automatic belief and our use of the senses and our general thought, that is naturally tacit, but what we might explicitly tap into when we go in for the well known method of brainstorming, ensures that we are all likely to be open to criticism, whether we want to be or not.

We are told that “Christianity has been successful partly because it satisfied a universal interest in an explanation of the world” (p.52). Many creeds are not concerned directly with the truth but rather with what Francis Bacon might call false idols, with ideas as ends in themselves, or dogmas, rather than with truth, though to be clearly seen or thought to be false will tend, eventually if not immediately, to discredit such sacred ideas or dogmas.

Francis Bacon: Critical of false idols.

The author tends to see science as a competitor with religion. They can clash whenever religion makes a claim to the truth, but religion is not usually concerned with making a fresh enquiry to achieve a true if profane view of the world so much as the fostering of stable sacred dogmas that are worth cherishing. Any clash with science usually soon ends with religion giving way and retreating into the gaps that science remains indifferent to. Many religious people see enquiry as trouble. Science was always about enquiry but religion never was. As Popper repeatedly says, theology, where enquiry is important, is the road to atheism. Most religious people are content with the dogmas their religion holds to be sacred; those that they claim to already know. Further enquiry, or even any enquiry at all, was hardly ever a feature of religion. Most of the masses in any creed will still not know all that much about it and the bigger the membership, the lower most members in the middle of the Bell Curve will know. However, the creeds with big organisations will tend to have more knowledgeable experts. Small sects, by contrast, will have way greater average knowledge and the curve will be too flat to look like a bell. But it is highly likely that an expert from a big organisation might know more than the lot of them.

Popper is cited as holding the view that one needs to have a rational attitude but the author tends to rightly assume that we are all rational whatever we choose to do (p.58). Popper consistently wanted to put a stress on objectivity in science, to emphasise logic and the scientific method rather than the subjectivity of belief, that most other philosophers tend to think is the primary concern in the theory of knowledge and in the analysis of scientific procedure. Popper was less concerned with the philosophy of mind. Thus he repeatedly rejected belief as irrelevant to science, and that is quite right, of course. However, Popper unwittingly adopts a naturalistic device within his own philosophy of science by advocating honesty, because honesty is a matter of belief.

Popper is again cited saying that the assumption that we should make no assumptions is not very practical or even consistent (p.58). This would be the case even if beliefs were not automatic assumptions that thereby forced us to assume. The author thinks that both assumptions leads to undue pessimism about understanding arguments (p.58) for Popper thinks it depends on whether we have adopted the right attitude earlier (p.59). Otherwise, he feels arguments will not impress people unless they first adopt the use of reason. This idea that Popper has is simply false. Our attitude is not germane to what we understand. We cannot control what we see as true in the way that Popper often imagined. Our attitude hardly matters to what we immediately see as true, though it might well stop us from training such that we never achieve the background knowledge that is needed to understand science.

The author says that irrationalism is logically tenable but not psychologically so (p.59) which presumably means that it is valid but fails to refer to any truth, thus it is not sound. He notes the oddity that Popper says that even a convincing argument will not convince without this adoption of a rational attitude. ”If there are arguments that can persuade one to adopt the rational attitude in general, then one can be affected by rational argument without having first adopted he rationalist attitude (p.59). The point here seems to be that we have a problem if we do not assume that people are open to argument to begin with.

Until he was won over by Bartley (p.60) Popper adopted the bogus meme of faith. But as belief cannot be controlled, we cannot be faithful. There never was the very common retreat to commitment that Bartley feared. Commitment cannot directly affect what we see as true. What we want to be loyal to cannot affect our understanding. Faith is like the closed mind in being a philosophical idea that has no external reference. There is no faith.

Religion is not a matter of everyday observation. It is mainly a matter of value rather than of observation, so religious ideas are little tested. But no theory or value paradigm can rule out a counter example, or fully control what we think. If we see a fact that looks like a refutation then we will feel we have a refutation, even if a moment later we see it as a mere error. The assumptions that Bartley made about people living in a dream world will not even allow him to explain how people get dressed every morning, let alone explain the growth of science (p.61).

Common sense tends to over-rate the depth and the stability of our beliefs as well as thinking that we can control them. Popper goes along with all that as part of his anti-naturalistic adoption of rationality and the scientific method as a matter of choice. The author tends to abandon that idea. What makes belief look stable is the world itself by having an impact through our senses in shaping up most of our conjectures. This is why the fresh revision reproduces much the same content whenever we look at the same objects. This is not a long lasting belief but rather a fresh ephemeral belief capturing similar or even the same content, owing to that being reinforced by the way the world is. The world will aid us to reproduce the same content in fresh beliefs today that we had in the beliefs we had last week, or even decades ago. But revision goes on even if revision does not always lead to amendment of content in the fresh beliefs we automatically create or fabricate today. The main determinate of stable content in fresh thought or belief is the external world itself. Thus if you were an old man who still had an old chair from childhood in your study that your grandson accidentally slightly ripped just recently then you would see the rip when you looked at it. You would not see the chair with a stable belief lodged in your memory. There are no beliefs in our memory or any old beliefs at all, we create them ad hoc and spend them as we use them to revise the world with, usually in order to do something practical in the world. We re-check as we do whatever we do. All beliefs are ephemeral and all beliefs are superficial. That you do not want to see the rip in the old chair will hardly stop you from seeing it.

No ideology is going to be rich enough to capture everything about everyday life, even if the diligent ideologue has mastered all the theory. We usually tend to forget most theory anyway for fresh ad hoc assumptions. So when the Marxist meets the Christian it is the place they meet in that has more impact on their common understanding than their chosen ideology. They will agree on most things for we all agree on most things. This is the case; despite the fact that we need to make personal subjective assumptions to get access to the facts, for most assumptions will be pragmatic.

Thomas Kuhn: He thought we could not understand ideas we do not endorse.

Thomas Kuhn had the idea that we could not understand ideas that we do not endorse, that the theory we choose to adopt determines what we see. It is true that a theory can be a great heuristic to discovering new facts/objects but it does not prevent us from understanding a rival theory, as Kuhn tended to suggest, and still less phenomena that are at odds with the theory that we hold.

The author rightly says that both wishful and fearful thinking are rational and open to criticism. All beliefs are unjustified guesses, and believing what you wish or fear is one type of unjustified guessing” (p.125).

However, I would say that our beliefs are automatic guesses or assumptions. Assumptions in logic might also be called guesses too. The rule of assumptions in logic is that we can assume whatever we like. That rule is even easier than any rule of arithmetic or grammar. However, many philosophers seemingly forget it. Logic is not psychology but rather it is the abstract rules that we can use to test our thinking for coherence. However, it does mean that any assumption is quite rational. This means that any belief is quite rational. This basic rule of assumptions does not mean we can think as we like but rather that we can safely do so logically with any single assumption, as we only get invalid logic between many assumptions. Any single assumption is good enough to start from. There are no invalid single assumptions. All assumptions are in themselves quite logical. We, indeed, have no choice in this automatic belief but whatever we assume will be fine as an assumption in logic. It will be perfectly rational. Logic is used to test a thesis for its coherence, to see if our assumption fits with any other assumptions made by our thesis, to test for its overall validity. The use of argument is to test logically. We also, in addition to logic, use observation to test whether whatever we assume matches the external world, or the facts. This latter is not validity or logic but to do with the truth or the whether the external facts are aptly cited.

The text continues: “There are other types of unjustified guessing, for instance believing what you are told, or the opposite of what you are told. Rationality does not lie in how you come up with your guesses, but in how you test them once you have arrived at them” (p.125). Belief is a good heuristic for it provides us with automatic assumptions that our five senses then proceed to test. But whether we do believe what we are told is not ever a matter of choice thus it is never a matter of loyalty or of obedience either. But it will involve at least some repeated process of checking up on whatever we think is true.

Popper is reported (p.134) as holding that a deterministic account of belief would raise what is called an obvious problem: that determinism might be the reason we believe rather than the truth. Hilary Putnam puts a similar point but the point is very unrealistic. Belief is what we see as the truth but we all know that it needs checking and our senses do check whatever we believe anyway. No one holds that a belief is truth ipso facto , even though it is exactly what the person who still believes it thinks is the truth at any one time. The one time the ephemeral belief lasts will be a very short time. We are bound always to think again while we are alive. Suicide is the only way out of that revision.

Maybe Popper and Putnam held it to be a problem as they both, falsely and totally unrealistically, held that a belief could be stable, that it might prevent us from checking things out in some way. Determined automatic belief can never last as long as a minute. But most philosophers have an idea of belief that can only be like one of Bacon's false idols; an impractical idea that we use for conversation. We are bound to think that all we see as true is true and belief is about the truth.

Popper was just confused on choice and the truth. It is true that any belief might theoretically be false. But our beliefs cannot lock us into ideas in some way for as long as a single minute, but it seems that Popper thought that it did on this determinism of belief crowds out the truth idea. But the automatic turnover of beliefs is exactly what ensures that we are open to perpetual revision (p.135). The author here applies Popper's theory of propensities to the psychological effectiveness of refutations in a way that Popper might have approved of.

Fodor seems to be right in holding that we need to both process what we see and to believe in a mandatory manner (p.135).

The author tends to conflate beliefs and values as well as not getting the fact of how very ephemeral beliefs are. Values are a bit more stable. If the wife runs off with the milkman we will realise it in a jiffy but we may well feel heartbroken for years. Ideology is largely a matter of values rather than belief thus we see the apparent refutation but still hope the ideology might survive (p.138) and even if we realise it is false we may lament the fact for years. But values will usually need some factual basis to them such that if we see that the dogmas of a creed are glaringly false then we may soon find that we do not value it as we once did when we thought that the dogmas were basically true.

We can never act on just one belief-take, as in any action an abundance of fresh beliefs will be needed to do what we need to do and our beliefs will spring up ad hoc whilst we act. Often at the end of the action our beliefs will be different in content as we will have learnt by doing the action. Indeed, we may well have very distinct beliefs from the ones that we began with even half way though the task. Instead we are told of weak or strong beliefs but the latter seem to be the stuff of myth for there is no scope for strong or weak belief if this means some belief that can survive as long as a minute. But then the process of believing is distinct from the content of our beliefs. It is the belief that is fresh, rather similar to a frame in a cinema film but what it picks up in content could be very similar. Our senses revise the lot of what we see, our thoughts revise all that we think. We use our senses to create fresh beliefs whenever we do anything. We do check how things are whenever we act. We do rethink any ideas that we have.

Keynes had the idea that we learn very little after the age of thirty as he reports on the final page of his 1936 book. I do not deny that it gets ever harder to learn as we get older, but no matter how old we are, we do make fresh beliefs in order to do almost anything. If we suffer from dementia then we may even get to reject the solution of 2 as the answer of 1+1. We may think we now know better! However, it is easier to rethink similar ideas that we have often had before. Dendrites laid out in the brain aid what we have learnt earlier to return to mind with ease but this is never completely lacking in revision, even though revision often sees no need for any amendment.

Keynes: Had the idea we learn very little after the age of thirty.

The author tells us (p.148) that researchers have found recurring biases in typical human thought but in many accounts in the psychology textbooks the unrealistic biases seem to be in the theories of the researchers. They often hold that future danger is overlooked whenever people smoke, or that people often reject medical advice on other things. The researchers put this down to false optimism, but it is more likely that what we consume now, like cigarettes, is more important than the price we have to pay later and well worth that price to the smoker. Researchers, like Daniel Kahneman, often think it is right to hold future time as of equal value to the present but that is simply an unrealistic daft dogma that Kahneman mistakes for being an objectively sound value.

Oddly, the reports on this false optimism are said to be functional and have an advantage as against the lack of it, all things being held equal. By what criterion, then, do those college researchers think it is irrational? They seem to think the assumption of equality is neutral. However. no assumption can be neutral. We cannot shed the epistemological risk of error. To assume is to adopt a bias and thus to risk error. There is no risk-free fence to sit on. The author sums the psychological research up quite well thus: “all it shows is that we're not gods, we sometimes make mistakes, we're fallible. And it does not show that we are locked into these errors” (p.148). Indeed, the research could never find errors that we were locked into, or any example of the actually irrational. But the psychologists do seem to be better candidates for this label than their subjects do.

The author tells us how the criticised may well think that though the ideas look defeated, as far as they can see, they may not feel sure that the fault is not their own rather than that of the theory. A better propagandist might well have an obvious answer that they simply lack the wit to think of, at least just now (p.165). This is the “wise man in Edinburgh” meme that there is always the man that could successfully show that the criticism that seems to refute the theory is actually flawed. So the propagandist does not openly admit to the error, as a naïve falsificationist would. The propagandist still values the theory and it might be the case that it is not truly refuted though his mind still sees the problem that he will not admit. We are never free to think as we like but we can say what we like, or we can refrain from saying what we do not want to admit.

The author is quite correct to say there are no thoughtless emotions and no emotionless thought (p.171). Similarly, it is correct to state that most arguments are implicit (p.185) such that in almost any debate the assertions made are usually arguments with tacit premises.

A phenomenon that the author cites is that the elite hold very distinct values on issues like capital punishment (p.118-9). Yet the voters still support those elites. That is a bit of a puzzle. It indicates a de facto oligarchy rather than a democracy. Voters oddly usually do vote for those who hold ideas that they daily explicitly distain.

The author says that values relate to facts (p.194) even when it is moral values but many might hold that a necessary evil is still evil even though necessary. In most cases, when something is shown to be necessary we think it not evil and when something we want is shown to be impossible we soon cease to want it. The adoption of the Kant motto that “ought implies can” would make ethics into a science, of course. It would make a lot that the Christians have traditionally counted as sin look odd. I think it simply is the case that this practical clause of the hypothetical imperative is very often not respected in ethics and that it will continue to be rejected. Tom Paine was not incoherent in calling the state a necessary evil, though he was maybe wrong to think that the state was, in fact, necessary.

Hume is cited on the fact that the passions are open to reason (p.195). It seems to be quite right that our emotions are cognitive as the author says.

But this cannot affect the is/ought distinction (p.196). This is often put as a fact/value distinction but it might be better put as the belief/value distinction. Our values relate to the facts but they are not external to ourselves but rather internal phenomena that will be external facts only to another person. It will be a second order fact to others whatever we happen to value at any one time. The author cites G.E. Moore thus: “No truth about what is real can have any logical bearing upon the answer to the question of what is good in itself” but as I said in a paper given to the Popper Conference in 1997 the good is not a matter of value any more than the facts are of our beliefs. As Plato, and Kant following him, rightly held, morals are a matter of external Form: logic and emotions apply but the facts remain additional.

The author brings up Roemer on equality and he makes the point that Mrs Thatcher made in her final speech in the House of Commons; that we can either have more equality by political coercion, where all are worse off as a result, or a lot of inequality in free trade where the poorest groups in society are far better off, owing to the progress that free trade allows. But Adam Smith seems to be right when he sees free trade, or the market, as being the one force, without any realistic rival, for long run equality that has emerged in the last three or four hundred years. It is only in the very short run that the market throws up some inequality, but it is of the type that makes for long run equality. Free trade makes for things like market innovation, invention and short run higher wages where workers are in short supply that do favour a minority. But the long run equalising process of the price system is a levelling up process, as progress is thereby made for all in the long run.

“The whole of the advantages and disadvantages of the different employments of labour and stock must, in the same neighbourhood, be either perfectly equal or continually tending to equality. If in the same neighbourhood, there was any employment evidently either more or less advantageous than the rest, so many people would crowd into it in the one case, and so many would desert it in the other, that its advantages would soon return to the level of other employments. This at least would be the case in a society where things were left to follow their natural cause, where there was perfect liberty, and where every man was perfectly free both to choose what occupation he thought proper, and to change it as often as he thought proper. Every man's interest would prompt him to seek the advantageous, and to shun the disadvantageous employment.” [Adam Smith The Wealth of Nations (1776) book one, the opening lines of chapter ten.]

The author seems to overlook, as so many other authors do, that any interpretation is a matter of fact i.e. a different interpretation is a difference as to what the facts are claimed to be, or to which facts are most germane (p.221). It is not the case that we have the facts on the one hand with an interpretation in addition to the facts on the other.

A contradiction is spotted in Marx's main book where it is held that exchange is distinct from use value despite also holding that commodities need to have use value otherwise the labour contained in it is void (p.252). The reason why Marx wants to shed use value is so he can say that production for profit is not also for use but of, course, it is and it must be: ipso facto . It is quite futile for Marx to attempt to deny it. But it still washes with most of his readers. The author does a lot to fortify the attack on Marx that Popper made in the 1940s in a way that the Marxists will find less easy to deal with; though Popper did make a number of solid points which were smothered by his rather odd eulogy of Marx. We are reminded of what most readers of Marx today tend to forget, or at least overlook – the clash between the idea and reality. The labour theory of value holds that wages are at subsistence levels and that they are forever being pushed down to such levels (p.259). Marx had to apologise for that by saying that this was socially rather that physically determined even before he got his main book out, for it is all too clear that wages were not being pushed down to a physical subsistence level.

However, many Marxist propagandists do explicitly say that wages are constantly being pushed down and that they are now lower than they were in the early 1970s. They say that statistics show this as a fact. Yet it is clear that we have mass production for the masses with wages tending to go up since the 1970s. This Marxist meme looks like a ploy rather than a belief. The Marxist still do go on about the threat of falling wages despite the fact that wages have never stopped increasing in value, as it is a ploy to try to get wages up even further by trade union activity.

I think there is a good chance that the author has written what could be considered a future major classic for the book deserves such success. Whether it is to be so depends on the public but the author has done his part in what could be that end result.

Buy it at - www.amazon.co.uk

![]()

Top 50 books of all time : by Old Hickory:-

"I have limited the selection to the books I have read. I keep to the norm of not recommending to others books I have yet to read. Clearly, books I have not read by now suggests a judgement of some sort."

PDF version

of this article

![]()

Download

Requires Adobe Acrobat Reader. This is available

for free at www.adobe.com

and on many free CDs.

The Alternative

Bookshop

Which specialises in,

but does not limit itself

to, books on Liberty

and Freedom ... Book

reviews, links,

bestsellers, rareties,

second— hand,

best price on books,

find rare books.