My Orwell Right or Wrong

![]()

Why Orwell Matters, by Christopher Hitchens. Basic Books,

2002, 211 + xii pages.

A book review by David Ramsay Steele

At the end of his book on George Orwell, Christopher

Hitchens solemnly intones that “‘views’ do not really

matter,” that “it matters not what you think but how you

think,” and that politics is “relatively unimportant.” The

preceding 210 pages tell a different story: that a person is to be

judged chiefly by his opinions and that politics is all-important.

Why Orwell Matters is an advocate’s defense of Orwell as a

good and great man. The evidence adduced is that Orwell

held the same opinions as Hitchens. Hitchens does allow that

Orwell sometimes got things wrong, but in these cases Hitchens

always enters pleas in mitigation. Hitchens’s efforts to

minimize the importance of Orwell’s objectionable views, or

in some cases his inability to see them, paint a misleading

picture of Orwell’s thinking.

Orwell’s Anti-Homosexuality

One way of playing down Orwell’s non-Hitchensian views is

to attribute them to his unreflective gut feelings. We are to

suppose, then, that when Orwell thought things over, he

anticipated the Hitchens line of half a century later, but

whenever Orwell slid into heresy, it was because he allowed

himself to be swayed by his intense emotions.

Of Orwell’s opposition to homosexuality, Hichens says:

“Only one of his inherited prejudices––the shudder

generated by homosexuality––appears to have resisted the

process of self-mastery” (p. 9). Here Hitchens conveys to the

reader two surmises which are not corroborated by any

recorded utterance of Orwell, and which I believe to be false:

that Orwell disapproved of homosexuality because it revolted

him physically, and that Orwell made an unsuccessful effort to

subdue this gut response.

Orwell harbored no unreasoning, visceral horror of

homosexuality and he did not strive to overcome his

disapproval of it. The evidence suggests that, if anything, he

was less inclined to any such shuddering than most

heterosexuals. His descriptions of his encounters with

homosexuality are always cool, dispassionate, even

sympathetic. His disapproval of homosexuality was rooted in

his convictions. He was intellectually and morally opposed to

it.

Compare Orwell’s opposition to homosexuality with his

opposition to inequalities of wealth and income. Both of these

standpoints involve an element of moral disapproval, but both

are reasoned and thoughtful, both draw upon an elaborate

theoretical structure conveyed by an ideological tradition––in

the first case, fin-de-siècle preoccupation with degeneracy, in

the second, equalitarian socialism. How apposite would it be

to dismiss Orwell’s income-equalitarianism, one of the

foundations of his socialism, by saying that it was an involuntary

shudder, that he could not rid himself of an inherited,

unreflective prejudice?

Orwell’s anti-homosexual position (definitely not

‘homophobia’, which would suggest irrational fear) flowed

naturally from beliefs and values about which he was quite

forthcoming, though he never provided a systematic

exposition. Orwell held that modern machinery and

urbanization were inhuman and degrading. City life was

rootless, alienating, and demoralizing. Although there was no

going back to the organic rural community which had been

shattered by the industrial revolution, any more than there was

any going back to religious faith, both losses were sad and

wrenching––in this respect, Orwell’s outlook is akin to that

of Mr. and Mrs. Leavis. Industrial and scientific progress

could not be stopped without unacceptable consequences, but

were essentially malign.

Orwell was decidedly against birth control as well as feminism

and homosexuality.[1] He singled out “philoprogenitiveness”

(a high valuation for having children) as one of a handful of

essential precepts of any viable society. He believed (as did

most intellectuals in the 1940s) that western society was beset

by a crisis of declining fertility. He routinely equated decency

with masculinity and masculinity with virility and physical

toughness. He expressed contempt for people who took

aspirin. He did not welcome reductions in the working day or

increasing affluence, because more leisure and more comforts

were liable to lead to ennervating softness and a life of

meaningless vacuity. As was remarked by someone who knew

him well, his human ideal would have been a big-bodied

working-class female raising twelve children.[2]

Though I cannot unpack all this here,[3] it forms part of a coherent and cogent worldview, and relates Orwell to the

“anti-degenerate” thinking of influential writers like Max

Nordau. During the Second World War, Orwell repeatedly

insinuated, or more than insinuated, that “pacifists” were

homosexuals and therefore cowards. The “nancy poets,”

Auden and his friends, were a favorite target. Apparently no

one ever explained to Orwell that ad hominem arguments are

generally fallacious, and he often made his point by unfairly

questioning the motives of those whose views he was

combatting.

Above all else, Orwell was a rhetorician and a propagandist. He doubtless sincerely believed that homosexuals were more

inclined to be cowards and therefore more inclined to be

politically against war. But he certainly chose this kind of

argument because he thought it would work as an instrument of

persuasion, and perhaps it did. One remarkable thing, though,

is that the ‘pacifist’ views Orwell assailed in this manner

were precisely the opinions he had himself held until quite

recently, and had enthusiastically propounded for almost a

decade.

Among advanced and humane thinkers in Orwell’s day, there was still an overwhelming consensus that homosexuality was pathological. This had been the view of Krafft-Ebing and of Freud, for instance. The theory was still popular among intellectuals that the alienation of urban life encouraged masturbation, which led to all the perversions, particularly homosexuality. It is not especially surprising that Orwell, who was never one for intellectually striking out on his own, would assimilate this predominant view. At this time, anything perceived as sexual ambivalence was quite commonly taken as a symptom of decadence and disintegration, as witness, among many examples, the figure of Tiresias in The Waste Land.

Orwell and friends

In the mid-1930s Orwell resisted conversion to socialism

because he associated it with cranky and degenerate practices,

including vegetarianism, nudism, teetotalism, and sexual

abnormality. After he had become a socialist, he saw these

associations as a liability to the socialist movement, and

therefore saw it as incumbent upon him to fight against them

within the left. He perceived middle-class people as more

susceptible to crankiness than working men, and went out of

his way to emulate what he identified as working-class habits,

even to the extent of slurping his tea out of his saucer. Orwell’s machismo is therefore intimately linked with his

worship of the proletariat.

Orwell’s Anti-War Phase

Another of Hitchens’s techniques is to to tell us what Orwell

must have been thinking when he arrived at his mistaken

views. He reconstructs Orwell’s thoughts so as to offer a

rationale for Orwell’s views which is acceptable to

present-day political correctness and to Hitchens, while it may

not be the rationale that would have occurred to Orwell. Here’s an example:

So hostile was Orwell to conventional patriotism, and so horrified by the cynicism and stupidity of the Conservatives in the face of fascism, that he fell for some time into the belief that ‘Britain’, as such or as so defined, wasn’t worth fighting for. (p. 127)

Notice that Orwell “fell,” rather than reasoned his way, into

this position. Because Orwell’s anti-war standpoint up to

August 1939 is an opinion that Hitchens disagrees with, it is

implicitly attributed to Orwell’s emotional reactions, and these

reactions are presented sympathetically. We are invited to

admire Orwell’s motives and ignore his arguments.

However, this reconstruction of Orwell’s motives for being a

“pacifist” is not convincing. It is not a report of the reasons

given by Orwell, or by the bulk of the left, whose anti-war

theories and attitudes Orwell shared. You would hardly guess

from Hitchens’s remarks here that Orwell observed the

growth of anti-fascist pronouncements by Conservatives and

viewed them with concern as signs of warlike intentions

towards Nazi Germany, or that he condemned the

Chamberlain government for its arms build-up.

Orwell’s view, prior to his conversion to a pro-war position,

was very much in line with the “pacifism” of the left, harking

back to the First World War and expecting the next war to be

similarly indefensible. If, as Hitchens quite reasonably does,

we take Orwell’s real career as a writer as starting in October

1928, then for more than half of that career Orwell was a

“pacifist”. Orwell joined the Independent Labour Party

(I.L.P.) and his anti-war views were quite similar to those of

other I.L.P. members; he left the I.L.P. after he began to

support the war.

Orwell accepted the common leftist view that “fascism” was

nothing other than capitalism with the gloves off, and that going

to war would make Britain fascist (or speed up Britain’s going

fascist, which was probably inevitable in due course) so that no

true “war against fascism” was possible. War against

fascism, then, could only be a feeble pretext for a war driven

on both sides purely by the economic rivalry of capitalist states.

Here, as time and again throughout Hitchens’s book, we see

Hitchens concealing from his readers (inadvertently, for

Hitchens does not quite grasp it himself) that Orwell has a

reasoned way of arriving at conclusions Hitchens doesn’t

like. Orwell, of course, did not think up the reasoning or

conclusions for himself, but adopted both from the leftist

discourse of the times, though within the range of views on the

left, he selected some positions in preference to others, and

then engaged in controversies with fellow leftists.

The Banality of Orwell’s Politics

Hitchens praises Orwell for having noted that Catholics tended

to be pro-fascist. But it is misleading to present this as though

it were an isolated aperçu, without mentioning that Orwell was

doggedly anti-Catholic. In a letter to a girl-friend he casually

dismisses one writer as “a stinking RC,”[4] though there may

be an element of self-mockery here with respect to his own

anti-Catholicism, which was notorious among his

acquaintances, for earlier in this letter he refers to “my hideous

prejudice against your sex, my obsession about R.C.s, etc.” Orwell was very much a Protestant atheist; in his youth there

had been a vigorous Catholic movement in British letters,

against which he reacted strongly; Orwell saw the Catholic

Church as an old and still formidable enemy of freedom of

thought.

It’s perhaps necessary to add, since this seems so strange

today, that Orwell lived in a culture where it was

unquestionably the done thing to make derogatory or laudatory

generalizations about entire groups of people, however defined,

and at the same time minimal good manners to treat individual

members of those groups with complete respect, as well as

sporting and decent to take individuals as one found them. On

a personal level, Orwell was open and considerate to

homosexuals, Catholics, and Communists.

Hitchens often gives the impression that Orwell’s opinions

were exceptional, and occasionally seems to imply that Orwell

was almost isolated. This is a popular take but it won’t bear

examination. In broad outline, Orwell’s political views could

scarcely have been more commonplace. For the most part,

they were the leftist orthodoxy––and that means the

intellectuals’ orthodoxy––in the 1930s and 1940s. They

were mainly the political correctness of his day, just as

Hitchens’s views are of his. And on the rare points where this

characterization might be disputed, Orwell’s views were still

far from outré in that milieu at that time.

Hitchens’s primary exhibit is Orwell’s attitude to “the three

great subjects of the twentieth century . . . imperialism, fascism,

and Stalinism” (p. 5). By “imperialism” Hitchens means only

the British empire: he is an enthusiastic supporter of American

imperial expansion today. By “Stalinism” he means

Communism, his years on the left having left him with the habit

of being semantically charitable to Trotskyists. And within

“fascism” he loosely includes both National Socialism and

Spanish Nationalism. A crucial premiss of Hitchens’s thesis is

that being simultaneously opposed to these three entities was

unusual. This is a simple factual error. Thousands of people

held these views.

As an example, let’s look at Bertrand Russell, probably the

most influential writer of the British left in the 1920s and 1930s,

someone who knew Orwell and someone from whose opinions

on political questions Orwell seldom greatly diverged (though

their views on culture and personal fulfillment were quite

unalike). Orwell had a short life, so that some of the writers

who had influenced him in his youth outlived him––another

was George Bernard Shaw.

Russell was an active and outspoken opponent of the British

empire. He was chairman of the India League, pressing for

Indian independence. Russell was always a committed

opponent of Fascism, Naziism, and the Spanish Nationalist

rebels.

Immediately after the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia in

1917, Russell displayed some general sympathy for the new

regime. He then visited Russia and wrote The Practice and

Theory of Bolshevism (1920), shocking many by his bitter

opposition to Communism (Bolshevism renamed itself

‘Communism’ just around this time). Russell remained

resolutely opposed to Communism until Orwell’s death and

then until at least 1958 (when he began to soften his opposition

to the Soviet Union because of his belief that the extinction of

humankind through thermonuclear war had become a serious

likelihood).

In the 1930s, both Russell and Orwell were at first opposed to

the looming war with Germany, both were classed as

“pacifists”, and both switched at around the same time to

support for the war. Russell wrote the anti-war book Which

Way to Peace? (1936), while Orwell wrote an anti-war

pamphlet which was not printed and has not survived, though

we can figure out much of what it must have said by scattered

remarks he made at the time. As Hitchens notes, Orwell also

tried to persuade his friends to form an illegal underground

group to sabotage the war effort.

Orwell reports that he changed his view about the war as the

result of a dream, on August 22nd 1939, ten days before the

outbreak of war. Hitchens’s statement that Orwell became

pro-war when “the war itself was well under way” (p. 127) is

thus inaccurate, though it is true that Orwell’s new position

did not become widely known until after the war had begun. Russell is on record as having switched to support of the war

by early 1940. He explained his change of position in a long

letter to the New York Times in February 1941,[5] in which he

dated his re-appraisal to the Munich agreement, and especially

to Hitler’s subsequent breach of that agreement by occupying

what remained of Czechoslovakia.

Most leftists at the beginning of the 1930s were anti-war (or,

as they were loosely called, “pacifists”).[6] Some remained

against the war, but many, including Russell and Orwell,

switched to support for a war against Hitler. I mention this to

emphasize that in case Hitchens wants to take support for the

British war effort as evidence of anti-Naziism, Orwell was a

late convert to support for the war effort (as Hitchens, of

course, fully acknowledges), and in this respect was a fairly

ordinary leftist intellectual of the period. Though there isn’t

space to document it here, Russell’s commitment to all three

of Hitchens’s correctness tests was more resolute, more

unswerving than Orwell’s. At times, for instance, Orwell

wobbled on the issue of Indian independence, asserting that it

was not really practicable (just a few years before it became a

reality).

Goodbye to the Empire

Aside from Russell’s views, there is much wider evidence for

the broad opposition to the empire, to Naziism and Fascism,

and to Communism. The tide of leftwing support for

dismantling the empire was so strong that the Labour Party,

following its landslide election victory in 1945, was able to rush

through independence for Burma and India.

After all, what was at stake? There had long been a widespread view within British politics that the empire was a net drain on Britain’s resources and would better be abandoned.[7] The majority of those in favor of holding onto the empire accepted that the colonies would gradually acquire more self-government until they achieved ‘dominion status’, the stage reached by countries like Canada and Australia. India in the 1930s was already largely self-governing, except for foreign policy, and more self-government would no doubt have arrived even under Churchill.

Orwell and T.S. Eliot defend the Empire at the BBC

During the war, the Indian Congress, under Gandhi’s

inspiration, opposed the war and took the position that the

Japanese or Germans would be no worse as rulers than the

British. Britain therefore suspended the Congress and imposed

martial law in India, an important piece on the strategic

chessboard. Though critical of martial law, Orwell (again, like

Russell) was not in favor of giving India independence while the

war was going on, a position that flowed automatically from his

support for the war effort.

Orwell believed that the empire was “a money racket,” that

Britain benefitted economically from exploitation of the

colonies, and that decolonization would necessarily bring about

a sharp drop in British living standards. Orwell, writes

Hitchens approvingly, “never let his readers forget that they

lived off an empire of overeseas exploitation, writing at one

point that, try as Hitler might, he could not reduce the German

people to the abject status of Indian coolies” (p. 44). Orwell

might be forgiven for overlooking, in the heat of the moment,

that the Indian coolies’ status was abject before the British

arrived, after which it became less abject, but what to make of

Hitchens, all these years later, holding aloft this daft remark as

if it were a penetrating observation?

The abandonment of the empire coincided with the beginning of

the most rapid rise in British living standards ever experienced.

Taken overall, the empire probably was a net drain on British

resources. Certainly, there is no clear indication that the British

people as a whole suffered economically from giving up the

empire.

The Left Loves Orwell

Orwell wrote for leftwing intellectuals, they were his intended

audience, and he strained to make his opinions acceptable to

them. He was adroit at trimming his utterances to gain

maximum acceptability by the left. When, in his final years, he

suddenly attained literary fame, he acquired a much larger

audience. and this was embarrassing, like one of those

Hollywood comedies where someone whispering to an intimate

acquaintance discovers too late that the public address system

has been switched on, and his words are being carried to

everyone in town.

Hitchens reproduces some choice examples of leftist hostility to

Orwell. Any Communist Party member or fellow-traveller and

any orthodox Trotskyist defender of the Soviet Union as a

progressive workers’ state, was bound to regard Orwell as a

bitter enemy. Hence the nasty attacks by Raymond Williams,

E.P. Thompson, and Isaac Deutscher, which Hitchens deftly

dissects. It is rather surprising that Hitchens doesn’t similarly

excerpt some of the feminist examples of anti-Orwell diatribe,

among which Daphne Patai’s is, though sometimes unfair,

often quite perceptive.[8]

It is easily confirmable that the bulk of books and articles on

Orwell are both leftist in political orientation and very

well-disposed towards Orwell. The left has all along been

predominantly pro-Orwell. The most common view among

leftists is that Orwell is the property of the left, and that it is

therefore outrageous if a rightwinger cites Orwell in opposition

to totalitarianism. If you start researching Orwell, you soon

lose count of the times you have read about the sacrilege of the

John Birch Society in using ‘1984’ as a telephone number.

A particularly crude example of the most prevalent leftist view

is Orwell for Beginners.[9] The For Beginners series is a set

of socialist tracts, in the form of easy introductions to modern

thinkers illustrated with cartoons. Orwell for Beginners is one

of the most inaccurate and amateurish of this commercially

successful series; it exemplifies the conventional opinion that

anyone who mentions Orwell in criticizing socialism is doing

something unconscionable, because, to a leftist, Orwell is ‘one

of ours’.

Hitchens refers to “the intellectuals of the 1930s” (p. 56) as though most of them were pro-Communist. He mentions Orwell’s “innumerable contemporaries, whose defections from Communism were later to furnish spectacular confessions and memoirs” (p. 59). Hitchens is not alone in exaggerating the importance of Communist influence in the 1930s. The notion that most British intellectuals were bowled over by Communism is an inflated legend.

Orwell in Spain. His wife is sitting in front of him, to the right

There were those very few intellectuals, like Maurice Dobb

and Maurice Cornforth, who remained Communists

throughout. There were those promising young intellectuals like

Christopher Caudwell who became Communists and died

fighting for Communism in Spain. Whether they would have

remained Communists for long had they survived a few more

years is not certain. I doubt it. There were those who enjoyed

whirlwind romances with Communism, like Auden and

Spender, and who could never furnish spectacular confessions

and memoirs because they had nothing spectacular to recall or

confess. There were some who left the Party or never joined it

but remained devout fellow-travellers. There were some sui

generis cases, like J.B.S. Haldane, whose wife left him and

wrote an informative book that may be considered a slightly

spectacular confession and memoir, and who himself faded

away without actually breaking with the Communists, or John

Strachey, a non-C.P. member who preached the Communist

line with great eloquence for a few years, then put it all behind

him to seek a career as a Labour politician. Then there were

the broad ranks of the left, who had spasms of sympathy for

Soviet Russia now and then, but who were not to be dislodged

from support for the Labour Party or the I.L.P., both

essentially anti-Communist organizations.

The rarity of the individuals who conformed to the pattern

described by Hitchens is illustrated by the fact that Richard

Crossman couldn’t find a single convincing British example of

a former Communist intellectual turned anti-Communist for the

landmark volume, The God that Failed, and not wishing to go

to press without one British specimen, had to make do with

Stephen Spender.

The lack of any such examples did not arise because large

numbers of intellectuals joined the Communist Party and never

left it. It arose because very few joined the Communist Party

at all, and nearly all of those who did left quickly before they

could get up to any skullduggery worth memorializing. My

guess would be that prior to 1941 more British intellectuals

joined the I.L.P. than joined the C.P.G.B. And, it goes without

saying, far more joined the Labour Party than either of those. The gigantic Labour Party, with a membership of millions,

operated a rigorous and active policy of excluding all members

of the Communist Party or any of its front organizations.

To say all this is not to belittle the effectiveness of the

Communist Party of Great Britain. It had an extraordinary

impact on British political and intellectual life, given that it was

always such a small group of people with so little popular

support.

It might be contended that the real influence of the Communist

Party was not in its membership but in the spread of

pro-Communist ideas among non-C.P. members. But first, this

too can easily be exaggerated. Much of it was akin to Western

admiration for Japan in the 1970s. It did not mean that the

admirers wanted to do the bidding of the admirees.

Second, Orwell was not as implacable an anti-Communist as is

often supposed. The Road to Wigan Pier, for instance, has

some cracks against the Communists and some compliments to

them. It comes down in support of their line du jour, the

Popular Front, and it dismisses resolutions “against Fascism

and Communism” with “i.e. against rats and rat poison,”[10]

a remark as idiotically pro-Communist as anything in Les

communistes et le paix.

But Stink He Does

After Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier came out in 1937, Orwell was twitted by Communists, who gleefully quoted his scandalous slander against the English workers: that they smelled. Orwell branded this a “lie” and persuaded his publisher Victor Gollancz to make a fuss about it.

The British working class in the 1930s. But did they smell?"

Hitchens indignantly denies that Orwell wrote the sentence,

“The working classes smell.” Hitchens vouchsafes that this

would be a “damning” sentence, a “statement of combined

snobbery and heresy.” All his hormones of outrage firing,

Hitchens rushes to poor Orwell’s defense: Orwell “only says

that middle-class people, such as his own immediate forebears,

were convinced that the working classes smelled” (p. 46). According to Hitchens, to accuse Orwell of saying that the

workers smelled is a “simple––or at any rate a

simple-minded––confusion of categories,” and he refers

readers to The Road to Wigan Pier, where what Orwell says

about the odiferous working classes can be “checked and

consulted.”

A pity, then, that Hitchens did not take a minute or two to

check or consult it. Orwell broaches the topic of proletarian

smelliness by stating that in his childhood “four frightful

words” were “bandied about quite freely. The words were:

The lower classes smell.”[11] So far this is consistent with

Hitchens’s reading, and must have been where Hitchens

stopped. Orwell now pursues this theme for three pages.

At first he does not strongly commit himself on the factual issue

of proletarian redolence, though he does imply that the

comparative uncleanliness of navvies, tramps, and even

domestic servants is a matter of observation. He quotes from a

Somerset Maugham travel book: “I do not blame the working

man because he stinks, but stink he does. It makes social

intercourse difficult to persons of sensitive nostril.” Then

Orwell confronts the inevitable factual question:

Meanwhile, do the ‘lower classes’ smell? Of course, as a whole, they are dirtier than the upper classes. They are bound to be, considering the circumstances in which they live, for even at this late date less than half the houses in England have bathrooms. Besides, the habit of washing yourself all over every day is a very recent one in Europe, and the working classes are generally more conservative than the bourgeoisie. . . . It is a pity that those who idealise the working class so often think it necessary to praise every working-class characteristic and therefore to pretend that it is meritorious in itself. (p. 121)

The “Meanwhile” indicates that though Orwell feels he can’t

evade answering the question, he wants to put it in its

unimportant place, as an aside to his main argument. He

avoids answering it directly or literally, while making his

meaning quite clear: the smelliness of the lower classes is not a

false belief held by the upper classes, but a fact.

A little later Orwell mentions the notion “that working-class

people are dirty from choice and not from necessity,” again

accepting that they are dirty while trying to leave that point in

peripheral vision. “Actually, people who have access to a

bath will generally use it” (p. 122). He has already told us that

most households don’t have bathtubs, which means that the

great majority of working-class people don’t have baths in

their homes. Earlier, Orwell has closely identified being dirty

with smelling (pp. 119–120), so there is no room to interpret

him as accepting the griminess of the lower orders without also

acknowledging the olfactory corollary.

We see then, that despite some references by Orwell to the

middle-class belief that the lower classes smell, worded almost

as though this belief were in itself wrong, Orwell ultimately does

not flinch from the objective fact that the English working

classes of 1936 are dirtier than their social superiors like

himself, and that they therefore smell––though it’s not their

fault. This is not an invention of Orwell’s detractors, as

Hitchens heatedly asseverates, but Orwell’s very own

opinion. And Orwell’s opinion on this point is correct.

As an English working-class child in the 1950s, when things

were a lot better than twenty years before, I can recall that,

though most homes by then had bathtubs, it was out of the

question to pay for hot water to be available all the time. The

water was heated for the occasion, and when it was bath night,

once a week at most, barely enough was heated for one bath

per person; this meant that if the depth of water in the tub

exceeded about two inches, it would get uncomfortably cold.

(Showers did not become common among the English working

class until the 1960s.) You didn’t wash your hair as often as

you had a bath (so the shoulders of jackets and coats were

always greasy, as therefore were places like chairbacks that

they frequently touched), and you “could not afford” (the

opportunity cost was too high, because of your low income) to

change your socks, underwear, or shirt every day. Clothes

had to be washed by the housewife, by hand, in a sink, with

soap flakes and then hung on a line, every Monday unless it

rained, to dry in the wind. Wearing the same clothes for many

days or weeks at a stretch is probably more conducive to a

noticeable smell than not bathing.

After The Road to Wigan Pier appeared, Orwell must have

kicked himself for having given the Communists such an easy

way to ridicule and discredit him. He blustered, not quite

honestly, parsing his written words, trying to make something

of the fact that he had never literally said “the lower classes

smell,” except in attributing these words to middle-class

snobs. Yet Orwell had unmistakably intimated that the

working classes smelled, and it is both careless and pointless of

Hitchens to maintain otherwise.

I’ve Got a Little List

In 1945 the Labour Party swept to power in Britain, with a

landslide electoral victory. Orwell saw himself as a supporter

of this government, though he speedily became disappointed in

it.

The British Foreign Office had a covert section known as the

Information Research Department (I.R.D.), concerned to

counteract Communist propaganda. George Orwell supplied

this department with a list of names, annotated with comments

mainly on their possible Communist connections, but also their

sexual habits, their characters, their ethnic backgrounds, and

their political soundness generally.[12] Orwell, it now seems to

some, was a McCarthyist before McCarthy.

This is a sensitive matter for Hitchens. He has an unbroken

record of detestation for ‘McCarthyism’, recently speaking

out in condemnation, yet again, of Elia Kazan’s co-operation

with HUAC in naming old Communist associates, which led to

the interminable vilification of Kazan by Hollywood and the

mainstream media. Hitchens has also been labelled

“Snitchens” by Democratic Party faithfuls, because he gave

testimony to Congress corroborating the fact that Sidney

Blumenthal had been spreading dirt about Monica Lewinsky at

the behest of his boss the Arkansas Rapist.

Here Hitchens tries to show that there is a great gulf between

what Orwell did and what McCarthyists did, but he is not very

convincing.[13] He draws various distinctions, some of which

are questionable, while others are quite genuine, though they

don’t gainsay a certain family resemblance between the two

endeavors.

“A blacklist is a roster of names maintained by those with the

power to affect hiring and firing,” says Hitchens. Why would

Hitchens say this, except to imply that Orwell’s list was not

truly a ‘blacklist’? Yet Hitchens quotes Orwell as writing

that “If it [the listing of ‘unreliables’ by the I.R.D.] had been

done earlier it would have stopped people like Peter Smollett

worming their way into important propaganda jobs where they

were probably able to do us a lot of harm.”[14] So Orwell’s

intention was that his list should be used as (or as part of) a

blacklist, to stop suspected Communists from being hired.

In another attempt at exculpating Orwell by legalistic definition,

Hitchens says that “a ‘snitch’ or stool pigeon is rightly

defined as someone who betrays friends or colleagues in the

hope of plea-bargaining or otherwise of gaining advantage” (p.

166). Does this mean that the same behavior for motives other

than “advantage,” such as sincere concern about the

Communist threat, would grant immunity from these labels? Many like Kazan who told the truth about their involvement

with the Communists to the F.B.I. or to HUAC did it as a

matter of conscience. And as for the fact that Orwell did not

personally know most on the list, Hitchens surely needs to do

more work on this angle. Can it be right to report to the

authorities one’s suspicions of a stranger’s Communist

sympathies, intending that this will hurt his employment

chances, and simultaneously wrong to report one’s definite

knowledge of a friend’s Communist Party membership?

On the Daily Telegraph’s reference to “Thought Police” in this connection, Hitchens protests that “the Information Research Department was unconnected to any ‘Thought Police’.” Must conservative newspapers be subject to a ban on the most elementary use of metaphor? Compiling secret government files on the ideological outlooks of people who have broken no law but are suspected of holding certain opinions is surely one aspect of the phenomenon satirized in Orwell’s Thought Police.

Was Orwell right to tell tales to the government?

My point is not that Orwell should not have given this list to the

I.R.D., though perhaps he shouldn’t, but that Hitchens should

be more understanding of “McCarthyism”, a term now most

often used for activities with which McCarthy himself was not

connected. Many of the elements now collectively referred to

as “McCarthyism” were wrong, and there were some

horrible injustices. But, contrary to most conventional

accounts, there actually was a Communist conspiracy; it was

no hallucination. When it is known that the Communist Party is

under the control of Moscow and its members are used for

conspiratorial work such as espionage and disinformation,

should it be out of the question to deny sensitive government

posts to Communists? That’s what Orwell and Tail-Gunner

Joe wanted to do, and I think both of them had a good general

case.

There is also a suggestion in Hitchens’s account that Orwell

and Celia Kirwan, his old flame at the I.R.D., were doing this

anti-Communist chore for democratic socialism, which renders

it more virtuous. It would surely be hard for Hitchens to argue

that democratic non-socialists ought not to be entitled to do

anything to combat Communism that democratic socialists are

entitled to do. Furthermore, since most Labour voters were

not “socialists” even in a very broad sense, there would be

something not very democratic about employing a secret

government agency for disseminating democratic socialism.

Hitchens is now a militant supporter of Bush’s war against

what Hitchens calls “theocratic terrorism,” though its next

step is apparently to terrorize a lot of non-terrorists in secularist

Iraq. Any threat posed to Americans by Islamic terrorism

today is paltry by comparison with the Communist threat of the

1940s and 1950s. The current “war on terror” is committing

more injustices than were ever committed by

“McCarthyism,” though the victims this time do not include

well-connected academics, bureaucrats, or movie stars. Far

from complaining about these injustices, Hitchens smacks his

lips at Bush’s magnificent “ruthlessness”. Hitchens has yet to

get his ducks in a row on the question of when it is right to give

information to the government.

My own view is that while you shouldn’t give the government

the time of day on a matter of drugs, pornography, insider

trading, or illegal immigration, when it comes to murder, rape,

or being a member of the Communist Party and therefore ipso

facto a Soviet agent, under the conditions of fifty years ago,

you may sometimes, according to the precise circumstances,

be morally obliged to co-operate with a government body by

telling it what you know. Whereas “McCarthyism” was

mainly concerned with people who lied about their past deeds

in behalf of a specific organization, Orwell’s list was mainly

concerned with people’s ideological sympathies whether or

not these had resulted in illegal acts. This aspect of the

comparison surely does not favor Orwell.

Why Orwell Matters, Really

Orwell matters because he was a great writer. Orwell’s social and political views are interesting, as are those of Samuel Johnson and Jonathan Swift, but they are most interesting for their nuances and their precise expression rather than for their gross anatomy, which was unexceptional and sometimes fashionably silly.

Orwell wrote two novels worth reading, Burmese Days and Coming Up for Air. He wrote a wonderful little allegory, Animal Farm. He wrote by far the most powerful of all dystopian stories, Nineteen Eighty-Four, which made many a Westerner feel like committing suicide and many a Communist subject feel like not committing suicide (because someone outside hell understood what hell was like). He wrote excellent accounts of his own experiences, somewhere between investigative journalism and sociological participant observation.

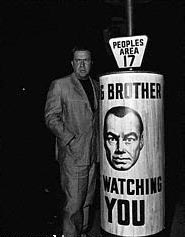

The language of politics

That’s quite a lot for an individual who died at forty-six. Yet

there is something of greater weight than all of these put

together: the numerous short pieces, the essays and reviews he

turned out rapid-fire, week by week, mainly to put bread on

the table. Although Orwell was not an original theoretician,

and his ideas, broadly characterized, were all off-the-shelf, he

had a superb gift for formulating them sharply, so that their

implications appeared fresh and unexpected. These writings

sparkle with polemical virtuosity; they throb with life.[15] They

will make entertaining reading for centuries to come.

"This article first appeared in LIBERTY magazine. Their

website can be found at

http://www.libertysoft.com/liberty/index.html "

[1] Orwell himself was sterile. He and his wife adopted a son, whom Orwell devotedly cared for after her death.

[2] Most of the above views are clearly propounded in Chapter 11 of The Road to Wigan Pier.

[3] See my forthcoming book, Orwell Your Orwell: An Ideological Study (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 2004).

[4] Complete Works, Volume 10, p. 268.

[5] Reprinted in Ray Perkins Jr., ed., Yours Faithfully, Bertrand Russell: A Lifelong Fight for Peace, Justice, and Truth in Letters to the Editor (Chicago: Open Court, 2002), pp. 177–182.

[6] This term was commonly used to include those who were not strictly pacifists.

[7] See for example Peter Cain, ed., Empire and Imperialism: The Debate of the 1870s (South Bend: St. Augustine’s Press, 1999).

[8] The Orwell Mystique: A Study in Male Ideology (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1984).

[9] David Smith and Michael Mosher, Orwell for Beginners (Writers and Readers, 1984).

[10] Road to Wigan Pier (London: Penguin, 1989 [1937]), p. 206.

[11] Orwell, The Road to Wigan Pier, p. 119. Orwell’s italics.

[12] George Orwell, Complete Works, Volume 20, pp. 240–259. Unfortunately Secker and Warburg have not handled the Complete Works happily. The hardbound edition is available only as a set at a monstrous price. Volumes 1–9 are Orwell’s nine book-length works. Volumes 10–20 comprise all of Orwell’s other output, arranged chronologically. These last eleven volumes, but not the first nine, have been released in paperback, with no volume number or series title on the cover or title page. None of them can be bought in a regular way from bookstores in the U.S., though they can be purchased from British suppliers online. They are usually listed by title, with no indication that they belong to the Complete Works. Volume 20 has the title Our Job Is to Make Life Worth Living, 1949–50.

[13] With the air of one setting the facts straight, Hitchens declaims that the “existence” of Orwell’s list “was not ‘revealed’ in 1996.” But no one has ever suggested that it was. The fact that Orwell had passed on this list to a secret government agency was revealed in 1996.

[14] Hitchens, p. 163; Orwell, Complete Works, Volume 20, p. 103.

[15] The essays are now available in one 1,400-page volume: George Orwell, Essays (Knopf, 2002). Also invaluable are the four volumes of The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell (Godine, 2000 [1968]).

![]()

Further reading:

"A collection of essays, reviews, articles and letters which Orwell wrote between the ages of seventeen and forty-six (when he dies). A splendid monument to one of the most honest and individual writers of the century."

Best places to buy:

![]()

![]() Why Orwell

Matters Christopher

Hitchens Hardcover

208 pages (1

October, 2002)

Publisher: Basic

Books; ISBN: 0465030491

Why Orwell

Matters Christopher

Hitchens Hardcover

208 pages (1

October, 2002)

Publisher: Basic

Books; ISBN: 0465030491

www.amazon.co.uk

£12.95+ P&P £2.75 = £15.70

Delivery Time 3-4 days

www.whsmith.co.uk £18.50 +

P&P £2.99 = £21.49

Delivery Time 2-4 weeks.

The Alternative Bookshop

Which specialises in, but does

not limit itself to, books on

Liberty and Freedom ... Book

reviews, links, bestsellers,

rareties, second-hand, best

price on books, find rare

books.

Laissez Faire Books

The World's Largest

Selection of Books on Liberty

PDF version

of this page

![]()

orwell.pdf

Download

Requires Adobe Acrobat

Reader. This is available

for free at www.adobe.com

and on many free CDs.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|