A Few Observations on the Passing of Augusto Pinochet

by Stephen Berry

In the last few months of the year of our Lord 2006, Latin Americans were asking themselves: Who will go first – Pinochet or Castro? The death of General Augusto Pinochet on 10th December provided the answer to that question but leaves many more unanswered. Why is it that Fidel Castro, who has been in power almost three times longer than Pinochet and has almost certainly committed even more crimes, continues to have supporters around the world while Pinochet was one of the most reviled men on Earth? Why is that Latin America remains such fertile ground for the authoritarian figures of the right and left? Over the last 60 years, the path leads from Peron, via Castro and Pinochet, to our good friend Hugo Chavez now wowing his supporters on the streets of Caracas and the campuses of Western academies.

There is no business like show business.

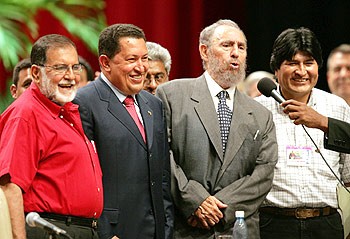

Schafik Handal, Hugo Chávez, Fidel Castro and Evo Morales, in Havana, 2004

It remains to be seen what murky dealings will be revealed when the communist regime finally falls in Cuba, but an inventory of the Pinochet years in Chile can already be made. Pinochet undoubtedly murdered and tortured many of his opponents. One estimate has him responsible for killing 3,197 people, torturing some 29,000, and sending thousands more into exile . His hand even reached abroad. Orlando Letelier, a Chilean exile and former foreign minister was blown up by a car bomb in rush-hour traffic on Sept. 21, 1976 in Washington D.C. Although Pinochet presented himself as squeaky clean, it turned out that he followed the iron rule of dictators in the 20 th century and salted money away in various foreign bank accounts. This aspect of Pinochet's image changed when in 2004, a U.S. Senate investigation stumbled upon the evidence that the general had stored millions of dollars in the former Riggs Bank and other financial entities using a dozen false identities. All this prompts one further question. Why did a country like Chile with a long history of democratic institutions allow such a man to come to power and rule for so long? To find the answer we should go back to the Chile of 1970.

At this time Chile was a democracy in good working order, already with distinct socialist leanings. Eduardo Frei, the previous Christian Democrat President (elected in 1964) had nationalized between one-fifth and one-quarter of all properties in a process of land seizure and redistribution. At the election of 1970, the Christian Democrats led by Frei got 27.8 per cent, the Conservatives, 34.9 per cent and a Popular Front (assorted socialists and marxists) coalition, 36.2 per cent. The leader of the Popular Front was one Salvador Allende who had already stood for President three times. Allende's political career went back to the 1930s and 40s. In a curious turn of events, it has recently been claimed that during this period he toyed with eugenic theories and may even have proposed a bill to sterilise the mentally ill.

Whatever the truth of this, it's a fact that Allende became a hero of the left and their story runs as follows. Allende was a democratic head of state swept into power by popular demand. From the start he was opposed by the Chilean Right, the army and, last but by no means least, American multi-nationals and the CIA. Using every trick in the book, these elements propelled Chile into economic chaos and were then able to overthrow Allende in a bloody coup. Moral of this story? It's impossible to make a revolution by constitutional means in Latin America. Carry on Castro!

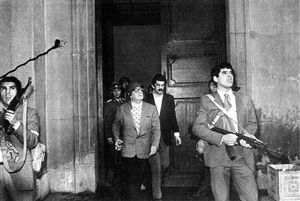

Salvador Allende's last photograph, taken shortly before his death

But let's look at this story a little critically for a moment. Was Allende always badly served by the Right? In Chile, when no candidate received an absolute majority, Chilean law provided that the President should be elected by Congress which might choose either of the top two candidates. We should be clear that after the election of 1970 there was nothing in the letter or spirit of the Chilean constitution which would have prevented the Congress from choosing the conservative candidate.. It could have been argued that the Christian Democrats and Conservatives were more easily able to form a government than Allende who was head of a diverse band of socialists. In fact the other parties, even though they held a majority in Congress decided to make Allende president in order to give the left a chance to exercise power. The position was not dissimilar to the UK in 1923 when Ramsay MacDonald was made the first Labour Prime Minister. It has to be said that the policies pursued by both men after taking office were anything but similar.

It's clear therefore that Allende was not opposed from the start. The Conservatives and Christian Democrats could have used the constitution to exclude him but did not. Perhaps the Chilean Right thought that someone elected with 36 per cent of the vote would realise he had not received a mandate to revolutionise Chilean society. Unlike Ramsay MacDonald, that is precisely what Allende tried to do. Upon assuming power, Allende began to carry out his platform of implementing the La vía chilena al socialismo ("the Chilean Path to Socialism"). This included nationalisation of large-scale industries, government administration of the health care and educational system, and a plan to seize all land holdings of more than eighty basic irrigated hectares. Why did Allende choose such a confrontaltional policy? It has been speculated that the upheaval in Latin America caused by the Cuban Revolution was one of the major causes of the Chilean failure. If Allende had not been determined to show that he was the equal of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, if he had not been under pressure from their supporters, he would have purseued a more prudent course, duly handed over power in 1976 and the world would never have heard of General Pinochet.

It has been claimed that the high cost of living and economic instability of Allende's presidency was organised by the CIA. It should be clear from the 1970s in the UK that strikes and demonstrations of hundreds of thousands of people can spontaneously occur in nationalised industries against a background of economic dislocation. In fact, they are almost inevitable. There is no need to call upon conspiracy theories which interpret all important events as the result of secret service actions. If the lorry drivers in Chile were unhappy, their expressions of discontent did not originate with CIA money. They were annoyed because the government wanted to nationalise and take over the means by which they earned their living.

Economic policies which resulted in shortages and an inflation rate of over 500 per cent were not the only problems to consult Chile. With an influx of armed foreign guerrillas from all over Latin America constituting a government tolerated miltia and the clandestine stocking of weapons, is it any wonder that the majority of Chileans who had not voted for Allende felt themselves imperilled. One year into Allende's term, the Cuban Embassy in Santiago had more staff members than Chile's own foreign ministry. Castro himself made a remarkable month long official visit to Chile in which he toured the country dispensing wisdom. Is it any wonder that Allende's opponents wondered if he intended to model Chile on the lines of Cuba.

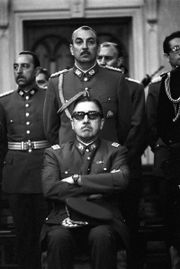

Pinochet and other members of the Chilean Junta

It was against this background that Pinochet was able to take over Chile and preside over its economic transformation. His reforms came about almost fortuitously when the general hired a coterie of young economists familiar with the ideas of one Milton Friedman, whom Pinochet had never heard of. Because free markets tend to bring about prosperity regardless of the moral nature of the regime that liberalises a country's economy, Chile prospered – as would China later. It's a fortunate side-effect of free markets that dictatorships don't last very long once they open the economy. The middle class tends to expand and develop a desire for political and civic participation. That is why Pinochet lost the referendum in 1988 and why Fidel Castro, who toyed with limited markets in the 1990s, quickly reversed course.

And so we return to the paradox of their respective popularities. Pinochet did bad things, left the Chilean economy in a reasonable state and permitted a referendum on his presidency. Castro did bad things, will leave the Cuban economy as a basket case and never – not ever – permitted a referendum on his presidency. Guess who will get the more sympathetic obituaries across the world?

![]()

Top 50 books of all time : by Old Hickory:-

Top 50 books of all time : by Old Hickory:-

"I have limited the selection to the books I have read. I keep to the norm of not recommending to others books I have yet to read. Clearly, books I have not read by now suggests a judgement of some sort."

PDF version

of this page

Download

Requires Adobe Acrobat Reader. This is available

for free at www.adobe.com

and on many free CDs.

|

|

|