Thomas Woods and His Critics:

A Review Essay

II

Which brings us to the section of The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History that has provoked the loudest howls of outrage, the two chapters relating to the Civil War: Chapter 5, “The North-South Division,” and Chapter 6, “The War Between the States.” Woods clearly wants to tender a neo-Confederate interpretation, in which slavery is shunted into the background as a motive for southern secession. In his preface, he characterizes as a cliché the statement: “the Civil War was all about slavery” (p. xiii). Yet notice the ambiguity in the little word “all.” Drop it out entirely, to read “the Civil War was about slavery,” and you have a statement with which even Woods would have to agree. In fact, later on, Woods disclaims any attempt to show “that slavery was irrelevant or insignificant” (p. 48). Change the word “all” to “only,” yielding “the Civil War was only about slavery,” and you now have a claim that no serious historian would endorse.

Woods is too scrupulous to fall into the careless or blatant errors of the more amateurish neo-Confederate books, such as Tom DiLorenzo's The Real Lincoln; Charles Adams's When in the Course of Human Events; or James and Walter Kennedy's The South Was Right.[1] The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History puts forward no such easily refutable claims as that the southern states had no concerns about slavery's future or that they really seceded over the tariff. The resulting account of the Civil War ends up far more mainstream than at first appears. Much of the two chapters' material, unaltered, could grace any standard treatment. A few of Woods's critics have gotten themselves all exercised over his assertion that “for at least the first eighteen months of the war, the abolition of slavery was not” the Union's war aim (p. 65). But no Civil War scholar would dream of denying the unmitigated truth of that assertion.

In only two significant respects does PIG try to sneak a neo-Confederate slant into its otherwise tame Civil War chapters. First, in Chapter 5, Woods writes “that the slavery debate masked the real issue: the struggle over power and domination” (p. 48). Talk about a distinction without a difference. It is akin to stating that the demands of sugar lobbyists for protective quotas mask their real worry: political influence. Yes, slaveholders constituted a special interest that sought political power. Why? To protect slavery.

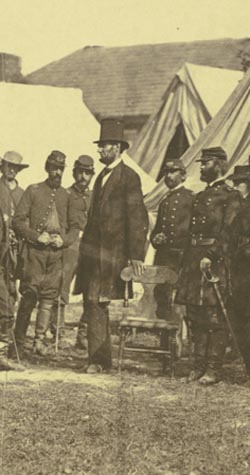

Lincoln visits the front line

Second, Chapter 6 boldly declares that “the Southern states possessed the legal right to secede” (p. 62). Here Woods lapses back into constitutional fetishism, of a particularly silly form. Why should any libertarian care one whit whether secession was a legal right? The vital, unaddressed question is whether the southern states had a moral right to secede. With respect to evaluating the American Revolution, do we ask whether it was legally justified or whether it was morally justified? If the secession of the slave states was truly immoral, than of what possible import was the legal right? On the other hand, if they indeed had a moral right to leave the Union, so what if doing so was illegal? Only a legal positivist would let the legality determine the morality of the act.

Whether the moral right of secession is conditional or unconditional is a question about which libertarian political theorists disagree. I have made the case for an unconditional right of secession in my own book on the Civil War.[2] But Woods dares not go down that path. Because if the states have a moral right to secede from the Union, regardless of motives or grievances, then counties have an unconditional moral right to secede from states, and individuals from counties. This not only sanctions the Confederacy's 1861 firing on a federal fort in Charleston Bay but also John Brown's 1859 raid on a government arsenal at Harpers Ferry, which was merely an attempt to apply the right of secession to the plantation.

Consequently, The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History enmeshes itself again in a futile debate over the Constitution's one-and-only proper interpretation, which as emphasized above, is a quest for a chimera. Woods grasps at the ratification ordinances of Virginia, New York, and Rhode Island, all of which he alleges reserved the right of secession. Back in the Constitution chapter, he did add a caveat to this allegation: “Some scholars have tried to argue that Virginia was simply setting forth the right to start a revolution, which no one disputed, rather than a right to withdraw from the Union. But this interpretation is untenable . . . ” (p. 18).

It is a pity that PIG does not provide the exact wording of these ratification ordinances among its “Quotations the Textbooks Leave Out.” Here is Virginia's: “. . . the powers being granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States, may be resumed by them, whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression . . .” The sentence containing these words, by the way, actually precedes as preamble the formal ratification. The wording in the New York and Rhode Island ratifications is almost identical.[3] I leave up to the reader's judgment whether such language invokes a legal right to secede or a natural right of revolution. Can such wording be reasonably construed as a precedent for secession? Probably. But as decisive proof? Assuredly not.

The Cost of War

All considered, Woods's two chapters on the Civil War sadly reduce to a missed opportunity. Hoping to present a neo-Confederate interpretation, he let his consideration for the facts get in the way. But that hope still prevented Woods from fashioning a libertarian interpretation. And so he is left with the worst of all worlds: a mundanely mainstream account that manages only to offend readers as neo-Confederate without actually being so and that scores few noteworthy libertarian points.

In the subsequent chapter, in contrast, Woods utterly fails to rein in his neo-Confederate sympathies. Chapter 7 on “Reconstruction” becomes therefore the book's weakest. I'll pass lightly over its argument that the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified illegally, still another manifestation of Woods's constitutional fetishism. Every American historian is quite aware of the historical irregularities surrounding this amendment's adoption, but so what? One may as well similarly argue that the Constitution itself is illegal, because its ratification clause violated the requirement for unanimous state consent to any amendment of the Articles of Confederation. The critical issue is whether the Fourteenth Amendment brought a net increase or decrease in the liberties Americans enjoy.

On this, like secession, libertarians find themselves divided, and pure logic does not require that even advocates of an unconditional right of secession also oppose the Fourteenth Amendment. By applying the Bill of Rights to the states, the amendment helped to halt and forestall some of the most egregious government assaults on the former slaves. It subsequently resulted in many court rulings that protected liberty, particularly those involving substantive due process or freedom of speech. On the other hand, the Fourteenth Amendment more recently has resulted in court rulings that violated liberty, particularly those imposing forced busing or local taxation. The most prominent libertarian defender of the Fourteenth Amendment is Roger Pilon of the Cato Institute; the most articulate libertarian detractor is Gene Healy, also of the Cato Institute.[4] Woods obviously includes himself among the detractors.

What is reprehensible about the Reconstruction chapter is not its denigration of the Fourteenth Amendment but its apologia for the Black Codes adopted by the southern states immediately after the Civil War. Contending that these codes have been misunderstood, PIG favorably quotes an essay written by H. A. Scott Trask and Carey Roberts.[5] “Most [of the codes] granted, or recognized, important legal rights for the freedmen,” the two authors state in the passage quoted by Woods (p. 81), “such as the right to hold property, to marry, to make contracts, to sue, and to testify in court.” Marxist historian Eric Foner, in his history of Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, notorious for its “political correctness,” hardly disregards these aspects.[6] He writes that the Black Codes “authorized blacks to acquire and own property, marry, make contracts, sue and be sued, and testify in court cases involving persons of their own color. But,” Foner adds, “their centerpiece was the attempt to stabilize the black work force and limit its economic options . . .”

The first two codes, of Mississippi and South Carolina, were the most severe. Mississippi's required all blacks to have written evidence of employment or face arrest. They were forbidden to rent land or own homes outside towns and cities. Other provisions applying only to African-Americans criminalized insulting “gestures” or language, preaching the Gospel without a license, or keeping firearms. South Carolina's code barred blacks from practicing any profession other than servant or agricultural laborer unless they paid a steep tax. The former slaves were required by law to sign annual contracts, labor “from sunrise to sunset, with a reasonable interval for breakfast or dinner” if they worked on farms, and if they were house servants, “at all hours of the day and night, and on all days of the week, promptly answer all calls and obey and execute all lawful orders and commands of the family in whose service they are employed.”[7] Nearly every one of the states' codes subjected blacks who were idle or unemployed to imprisonment or forced labor for up to one year, while “enticement” laws made it a crime, rather than simply a tort, to offer higher wages to a worker already under contract. In essence, the goal was to have government partly assume the role of the former masters by, in Foner's words, “inhibiting development of a free market in land and labor.”[8]

The excuse given by Trask and Roberts, as quoted by Woods (p. 81), for these provisions, is as follows: “Many [Black Codes] mandated penalties for vagrancy, but the intention there was not to bind them [blacks] to the land in a state of perpetual serfdom, as was charged by Northern Radicals, but to end what had become an intolerable situation—the wandering across the South of large numbers of freedmen who were without food, money, jobs, or homes. Such a situation was leading to crime, fear, and violence.”

Sometimes the line is very fine between empathically understanding the motives of historical actors and morally exculpating their actions. If Woods, through the quoted passage from Trask and Roberts, has not crossed that line with respect to white Southerners, he has skirted dangerously close. The former slaves did wander across the South and flock to cities immediately after emancipation. Many southern whites found utterly irrational and ungrateful, on the part of a people they had considered less than fully human, this desire to exercise a newly acquired freedom by doing something never permitted before and to perhaps track down lost family members who had been sold away. That any American writing in the twenty-first century who claims to be an advocate of liberty could likewise view such wandering as “intolerable” borders on disgraceful. As for flocking to the cities, which have always been magnets of economic opportunity, African-Americans showed themselves no less enterprising than other poor groups. Finally we come to Trask and Roberts's alleged violence, but the real wonder, which leaves most historians marveling, is that blacks visited so little upon their former masters.

The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History goes on to compare the Black Codes with the vagrancy and discriminatory legislation of the North. Even if northern laws were actually as bad, that hardly excuses the southern states. The Black Codes did indeed borrow from antebellum restrictions on free blacks, North and South, from northern vagrancy statutes, from the labor regulations of the Freedmen's Bureau, and from the apprenticeship system adopted in the British West Indies after emancipation in 1833 and later abandoned. But seeming parallels between northern laws and southern Black Codes are superficial, ignoring the profound impact that the antislavery crusade had in promoting throughout the North a free-labor ideology. During America's colonial period, many laborers had been indentured servants, a status they often (though not always) voluntarily entered into, yet involving mandatory service for a fixed term. By the time of the Civil War, indentured servitude was a thing of the past, legally as well as practically. Except for sailors who jumped ship and military personnel who deserted, an employee's breach of a labor contract was no longer a criminal but only a civil matter. Moreover, specific performance was no longer a remedy for such breaches, so that the North had moved, as the research of Robert J. Steinfeld has reminded us, to the modern conception of free labor, in which workers can essentially quit at will.[9]

The North did have vagrancy laws with penalties on the books that were unduly harsh. But northern courts mainly employed these laws to discipline prostitutes and petty thieves. The South's Black Codes applied vagrancy more broadly. Mississippi, for instance, counted anyone who “misspend what they earn” or who failed to pay a special poll tax levied on Negroes between the ages of 18 and 60; South Carolina explicitly counted persons who lead idle or disorderly lives, as well as gamblers, fortune tellers, unlicensed itinerant peddlers, and unlicensed thespians, circus performers, or musicians. Northern restrictions on free blacks, while inexcusable, were neither universal nor unchanging. By the mid-1850s Massachusetts had dispensed with every limitation on blacks voting or holding office, with its ban on Negro jurors, and with its prohibition of interracial marriage—legal disabilities that characterized all the Black Codes. Woods is quite correct that Illinois kept on the books until 1865 “a law imposing a fine of fifty dollars upon free blacks entering” the state. This law provided that any “unable to pay had their labor sold to whoever paid the fine for them and demanded the shortest period of labor” (pp. 81-2). However, as revealed by historian Leon Litwack (not someone who would ever overlook or pardon any transgressions against African-Americans), the Illinois law was a dead letter and almost never enforced.[10]

The harshest features of the Black Codes were never enforced either, because of intervention by the War Department's Freedmen's Bureau. An exception was southern apprenticeship laws. Although apprenticeship still existed in the North, the free-labor ideology had transformed it there from a category of unfree labor into a form of guardianship confined to minors. The Black Codes, in contrast, allowed southern courts to bind out the children of black parents without their consent or sometimes without their knowledge, simply because the court found the parents unable to support the children. In one North Carolina county, ten percent of black apprentices was over sixteen years old. As late as 1867, Freedmen's Bureau agents were still releasing Negro children from court-ordered involuntary apprenticeship.

Black Code legislation

The chapter on Reconstruction closes with an analysis of the Radical Republicans. Relying on Howard Beale, a progressive-school historian who wrote back in the 1930s, Woods attributes the Radicals' northern political success in the congressional elections of 1866 to their economic stances, particularly their support of high protective tariffs.[11] But he has misread his source, at least with respect to that election. Beale reveals that the Republicans were so deeply divided over the tariff that they had to soft-pedal the issue that year. As for Beale's overall thesis that the Radicals represented neo-mercantilist northern interests, subsequent research has found it wanting. The Radicals were far from united over purely economic policies. Some, like Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, were protectionists and inflationists. Others, like Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the leading Radical in the Senate, were advocates of free trade and hard money. When the Liberal Republicans, with their penchant for laissez faire, broke with their former party to oppose Ulysses Grant's reelection in the presidential race of 1872, their ranks included a host of former Radicals.

The Reconstruction chapter is responsible for one note of unintended irony on the book's cover. The original cover reportedly would have displayed a picture of George Washington. Washington was supplanted by General Longstreet, one of Robert E. Lee's lieutenants, undoubtedly to further Woods's neo-Confederate aspirations. Neither Woods nor his editors probably realized that, after the Civil War, Longstreet became a prominent Louisiana Republican and notorious southern supporter of Radical Reconstruction. For that reason, former Confederate General Jubal A. Early and a cabal of Virginians instigated a literary campaign to shift blame for the Confederate defeat at the battle of Gettysburg from Lee to Longstreet.

See Part I of Jeffrey Rogers Hummel's review of The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History..

See Part III of Jeffrey Rogers Hummel's review of The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History.

[1] Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (Roseville, CA: Prima, 2002); Charles Adams, When in the Course of Human Events: Arguing the Case for Southern Secession (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefied, 2000); James Ronald Kennedy and Walter Donald Kennedy, The South Was Right, 2nd edn. (Gretna, LA: Pelican, 1994). The numerous factual errors in DiLorenzo's book have been noted even by such favorably inclined reviewers as Richard Gamble in The Independent Review, 7 (Spring 2003), 611-4, and John Majewski in Ideas on Liberty, 55 (April 2003), 60-2. For a hostile review of both DiLorenzo and Adams, see Daniel Feller, “Libertarians in the Attic, or A Tale of Two Narratives,” Reviews in American History, 32 (June 2004), 184-95.

[2] Emancipating Slaves, Enslaving Free Men: A History of the American Civil War (Chicago: Open Court, 1996), epilogue. A libertarian treatise on political theory that ends up endorsing an unconditional right of secession is Chandran Kukathas, The Liberal Archipelago: A Theory of Diversity and Freedom (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

[3] Jonathan Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution . . . , 2nd edn. (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1836), v. 1, pp. 327-31, 334-7.

[4] Roger Pilon, “In Defense of the Fourteenth Amendment,” Liberty, 14 (February 2000), 39-45, 49, and “I'll Take the 14th,” 14 Liberty (March 2000), 15-6; Gene Healy, “Liberty, States' Rights, and the Most Dangerous Amendment,” Liberty, 13 (August 1999), 13-17, 24, and “The 14th Amendment and the Perils of Libertarian Centralism,” Mises Institute Working Paper (5 May 2000), available at Mises.org.

[5] H. Arthur Scott Trask and Carey Roberts, “President Andrew Johnson: Tribune of States' Rights,” from John V. Densen, ed., Reassessing the Presidency: The Rise of the Executive State and the Decline of Freedom (Auburn, AL: Mises Institute, 2001), p. 301.

[6] (New York: Harper & Row, 1988), p. 199.

[7] These quotations from the actual statutes come from a neo-Confederate work that Woods cites as an authority, Robert Selph Henry, The Story of Reconstruction (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1938), pp. 108-9. For a detailed monograph on the subject, see Theodore Brantner Wilson, The Black Codes of the South (University: University of Alabama Press, 1965).

[8] Foner, Reconstruction, p. 210.

[9] Robert J Steinfeld, The Invention of Free Labor: The Employment Relation in English and American Law and Culture, 1350-1870 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), and Coercion, Contract, and Free Labor in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

[10] Leon F. Litwack, North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790-1860 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961), pp. 70-71. Litwack cites the earlier research of N[orman] Dwight Harris, The History of Negro Servitude in Illinois, and of the Slavery Agitation in that State, 1719-1864 (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1904), p. 237, who could only find evidence of three attempts to enforce the law, all in 1853, and at least one of which was subsequently overturned.

[11] Howard K. Beale, The Critical Year: A Study of Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1930).

![]()

Further reading:

Murray Rothbard (with Leonard Liggio), Conceived in Liberty, v. 1: A New Land, A New People, the American Colonies in the Seventeenth Century (New Rochelle: Arlington House, 1975

Conceived in Liberty - Abe Books

The Alternative Bookshop

Which specialises in, but does not limit itself to, books on Liberty and Freedom ... Book reviews, links, bestsellers, rareties, second— hand, best price on books, find rare books.

|

|