|

The Rise and Fall of the British Welfare

State

"My vision is not just to save the National Health Service but to make it better. The money will be there, I promise you that. This year, every year." (Tony Blair, September 30, 1997)

Last year, the problems seem to arrive even before the outbreak of the winter flu epidemic. In The Times newspaper (October 18th, 2000) Professor Michael Joy, consultant cardiologist at St Peter's hospital, Chertsey, wrote to complain that he could not admit very ill patients from his Accident Department due to the unavailability of beds in the main hospital. He said, "If nothing is done, I guarantee within the next weeks there will be a mighty crash. Everybody in the Health Service is totally demoralised. I have never seen morale at such a low level in my 35 year career." We should make due allowance for the hyperbole of a worker under stress, but his claims cannot be dismissed. I have heard this song before. Last year, I had an interesting conversation with a doctor visiting from New Zealand as I was being wheeled to the operating theatre of one of Britain's NHS hospitals. Imagine my state of mind as she cheerfully compared the NHS to a Third World health service. Imagine my relief as the anaesthetic finally brought merciful oblivion. The NHS is the jewel in the crown of the British Welfare State, but it only arrived relatively late upon the scene (1948). The origins of the Welfare State go back to the late Victorian era and the desire to provide cheap housing for the poor, the best healthcare for all and pensions which made satisfactory provision for a comfortable retirement. If one country could be said to have influenced Britain in the

formation of its social policies in the late 19th century, that

country would be Germany. It is difficult now to envisage the

dramatic impact on the Victorian mind of the rapid unification

of Germany under the leadership of Prussia. France,

Britain’s main European rival for 250 years yet so

effortlessly dismissed on the battlefield of Sedan in 1870, was

now dominated with condescending ease by its dynamic

neighbour . There was a new kid on the block, and his every

movement was watched both eagerly and anxiously. Bismarck's social reforms were

the inspiration for the British

Welfare State >> Bismarck had temporarily banned socialist parties in 1878 and brought in a form of state welfare to placate the working classes and avoid a socialist revolution (In the late 19th century, Germany had the most powerful socialist party in the world). In the 1880s the German state began to provide accident, health and pension insurance and became the conscious model for Lloyd George and William Beveridge, the latter more than anyone being the architect of the British Welfare State. Beveridge visited Germany in 1907 and Lloyd George followed in 1908. It seems that the motivation of Bismarck and the British reformers was the same. The extension of the franchise to working-class men in the U.K. had occurred in 1885 and the institution of state social insurance was preferred to any socialist solution of the Marxist variety. The profit system, with what were regarded by many as its vagaries and caprices, was to be left in place. Indeed, Beveridge seems to have seen no conflict between state action and the free market. Interventionist social policies would strengthen the market and make it more efficient than ever.

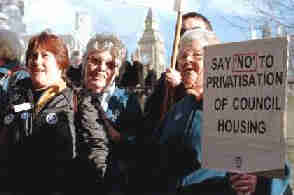

Subsequent developments have increasingly diverged from these early hopes and expectations. Pioneering work by The Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) in London has demonstrated the degree and vitality of the early private provision of the social services which were to become the province of the State. As British governments increasingly developed the Welfare State during the 20th century and snuffed out these existing mechanisms for private provision, there was no obvious sense of gratitude from the British citizens to their governments. Instead, we can trace continuing attempts by people to protect themselves from the poor level of welfare services provided by the State. The history of the Welfare State is the history of the flight from the Welfare State. Rent control came in during World War One (1915) and did not begin to be unwound until the late 1980s. The Local Government housing sector was established in the years after 1919 and was extended thereafter. Large ‘slum’ clearance programmes have transformed whole neighbourhoods and provided serious and unanticipated social consequences. In 1914, 90 per cent of dwellings were privately rented and 10 per cent owned. By 1993, only 10 per cent of dwellings were privately rented, with 20% provided by Local Government. Roughly 70 per cent of homes are privately owned. In other words, the 20th century in the U.K has seen homes go from being largely privately rented to being largely privately owned. Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s launched a successful programme to sell publicly-owned housing to the tenants. Government intervention in the housing market has simply driven Englishmen out of rented accommodation into inflation-hedged miniature castles which they could proudly call their own. In 1893 the famous Cambridge economist, Alfred Marshall, told the Royal Commission on the Aged Poor to resist the call for universal pensions advised by the Fabians, Sidney and Beatrice Webb. He warned that they, ‘do not contain … the seeds of their own disappearance. I am afraid that, if started, they would tend to become perpetual’. State intervention in the provision of retirement income was developed by Acts of Parliament in 1908, 1925 and 1948. By the last Act, state provision covered virtually the entire population, but here again the results have been rather different from those expected by the original reformers. During the 1990s there has been a minor scandal concerning the misselling of private pensions. It has been claimed that salesmen may not have given absolutely correct information concerning future returns to prospective customers. I would point out that when you purchase a private pension, the money you pay goes to the creation of a fund of capital which will be at your disposal when you retire from work. With the State Pension, your money is simply taken and used as if it were just any other form of tax revenue. When you retire, you are entirely dependent on the state’s capacity to tax for your future pension, and there is plenty of competition chasing those taxes. That is the great 20th century pensions swindle, perpetrated on a scale which would make the slickest of salesmen shake their heads with bemused admiration. Many people in the U.K. have fled from the trap of the State Pension. The last 30 years have seen a dramatic expansion of private pension provision, whether through company or individual schemes. Around two thirds of the UK population is now covered privately in one form or another. This is in stark contrast to Continental Europe where, with the exception of Holland and Switzerland, pensions are almost entirely funded by the state. For these countries, the problems of the ageing population will be faced in a particularly pronounced form.

It was in the area of healthcare that the most radical innovations were made by the state, and it is the in the area of healthcare where the problems have proved to be the most intractable. Private provision for healthcare at the start of the 20th century was extensive and growing with people paying by a variety of methods. By a series of measures in the first half of the 20th century, the British state brought in state health insurance for the payment of the cost of healthcare bills. But the postwar Labour Government was not satisfied with such routine measures. It came up with the marvellous wheeze of healthcare ‘free at the point of demand’. You simply turned up at the doctor’s surgery or your local hospital and treatment would be provided – no questions asked. If Socialists were never to realise their dream of a society where money and prices had been abolished, the NHS would remain to provide a gleam of the Promised Land. Intelligent readers with a brief acquaintance of economics might suggest at this point that an important service which is free at the point of demand will have a large take-up. And they will not be surprised to know that events have proved them right. Rationing has been the main mechanism by which consumption has been contained. Users of the NHS have to wait a considerable length of time for non-critical operations, and it matters very much in which area of the country you are located as to what standard of treatment you get.. The definition of what is a non-critical operation can be somewhat stretched. One woman caused headlines last year when she wrote to Prime Minister Blair to say that her husband had had to wait so long for his heart-bypass that he had tragically died. But it is rather unfair to expect Mr. Blair to sort out the problems of the NHS. History will see his efforts as a final futile exercise to save a decaying system. Blair is a modern day Necker, the minister of Louis XVI, whose reforms predictably failed to rejuvenate the enfeebled carcass of the Ancien Regime. In the face of a crumbling state system, people have done what is natural. They have made private provision for their future healthcare bills. Health insurance is becoming increasingly common as part of any job remuneration package, and I have no doubt that it will eventually match the company pension in popularity. Opinion polls still show the NHS to be popular in principle, but even this is gradually fading under the relentless pressure of poor standards and the never-ending cycle of crises. And there is the pertinent point made by Arthur Seldon, one-time economics’ guru at The Institute of Economics Affairs. Many opinion polls are less than informative unless a price label is attached. What people say and what they do can be quite different things. Even those people who profess to admire the NHS never miss the opportunity to take out private health insurance, and they are doing this is increasing numbers. The next 50 years will see the further withdrawal of the state from welfare services and its replacement by private provision. Libertarians of the more radical persuasion who would launch a putsch against the crumbling edifice of the Welfare State will be disappointed. Like Rome, it was not built in a day, and its fall will be a matter of decades, not something simply accomplished by a sweep of the revolutionary’s baton.

But the end, if prolonged, is also certain. Two-thirds of the population have made private provision for retirement and William Hague, the leader of the Conservative Party, wants to offer people under the age of 30 the chance to opt out of the state system entirely. The remainder of the public housing system is expensive to maintain. Paradoxically, it would be cheaper for politicians to give away state-owned houses and apartments to existing tenants and wash their hands of the whole business. Rising incomes will mean that people who as a matter of course expect a foreign holiday in a high standard hotel will not put with third-best in a NHS hospital. What will be the verdict of history on the British Welfare State? Its main crime was the replacement of the burgeoning and varied private provision of welfare with the uniformity and mediocrity of the state monopoly; the values of the entrepreneur substituted with those of the administrator. The aim of state welfare was to remove divisions in society. Ironically, the effect has been to make those divisions more visible. Nothing is clearer in the UK today than the accommodation gap between the homeowner and the tenant in public housing. Nothing is more poignant than the difference between the pensioner who uses an ample private pension to spend the winter months in Spain, and the pensioner dependent on state benefits alone to fund the winter fuel bills. The charge sometimes levelled thoughtlessly against the Welfare State – that it suffocates by providing security ‘from the cradle to the grave’ – is precisely misplaced. The Welfare State failed because the level of security provided was far below that which the citizen could rightly have expected at the end of the 20th century. Yet perhaps at a more important level, the impact of the

Welfare State may not have been that great. I have already

pointed out that in the areas of pensions and housing the vast

majority of people have been able to circumvent and mitigate

the low standards of welfare provided by the state. Even with

the NHS, we should be careful not to overestimate the

damage. Life-expectancy in the U.K. is not much different

from that of countries which have not enjoyed such an

extensive Nationalised Health Service. The state sector of the

economy in Britain has always been small and the effects of

the market are pervasive. Such factors as improved nutrition,

central heating, new drugs, and changes of behaviour may

well have had a greater impact on health than anything the

medical profession could have done. Men’s life expectancy

in the U.K. is rising as heart disease and the incidence of lung

cancer decline. Conversely, as women become more

‘liberated’ and adopt certain male behaviour patterns, such

as the increased consumption of cigarettes, the gender gap

for mortality statistics narrows. To put it bluntly: as women

behave more So there it is. A 150 year experiment draws ever so slowly to its close. But when in the year 2050 yet another socialist centenarian appears on our television screens lamenting the disappearance of the last remnants of the Welfare State, we should remember that her longevity was not the result of the rather second rate care afforded by the state. Rather, she exists as triumphant evidence of the market’s ability to improve the quantity and quality of our lives – even in the most unpromising of circumstances. |

|

||||||||

|

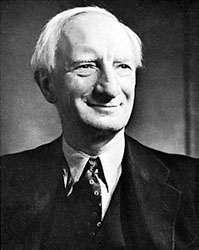

<< William Beveridge

founder of the Welfare

State

<< William Beveridge

founder of the Welfare

State

like men, they die more like men, and there is

nothing much that

doctors can do about it.

like men, they die more like men, and there is

nothing much that

doctors can do about it.