The Ten Worst Books of All Time (Part One)

![]()

By OLD

HICKORY

Here are the ten worst influential books ever to come off a printing press. Each book was either written by a bad man or it propagates very silly ideas, as in the case of the one cited woman.

If we can recommend the best 50 books ever written, can we not also counter this with the ten worst books? A single book can be good in some ways and bad in others. The Bible is excellent literature but very poor history, for example.

The trouble with the idea of ten evil books was put forward by Shakespeare’s Mark Antony when he says, in complete irony, that “the evil that men do lives after them, the good is oft interred with their bones” thus meaning that the evil is often interred with their bones. The problem with evil is that it soon vanishes, as there is no incentive to preserve it. It rarely leaves much of a legacy in culture, unless we count the legacy of the reports in history books. So maybe, the evil we need to counter the best books with relates more to the author’s ephemeral deeds recorded by history rather than to any that a book produced. We might, correctly, think that no book can do much harm, as there can be no harm in mere ideas. But there can be an evil author, even if most evil men will most likely not be authors. Clearly, the normal arbitrary nature of selection in any essay will be even more obvious here.

This will not be the case where evil is not seen as such, of course. The evil institution of the state survives, as it is not yet realised to be an evil institution by very many people. Most feel the state to be a boon, despite the evidence of every page of written history hitherto, for there seems not to be even one page of political history that does not relay the evil deeds of the state. A history of the arts or of science or of technology may well be very distinct but the history of the state will not.

The state has privileged allowances made for it, as with Ian Fleming's James Bond and his “licence to kill”. If it is the state then fine, but not if such were done by a person. Such double standards are vital to any tolerance of the state. But granting this privilege is merely foolhardy; it is stupid rather than evil.

Has the state a licence to kill?

Has the state a licence to kill?

There are some celebrated books that are not evil at all but have remarkably silly ideas in them. A book is often a very good propaganda tool for silly ideas. The ideas themselves remain harmless enough and we cannot soundly blame them for our own folly if we happen, or others happen, to see the ideas as if they were true; or in some way worthy. The mere thought of being political is never as bad, or as wasteful, as the internecine deeds of gratuitous coercion that makes up the normal behaviour of the crass practical political activity of the people who maintain the state. Unlike the list of the 50 best books, there is bound to be some clear incoherence here in this list of ten bad, or perhaps, simply silly books. I jump easily from the silliness of ideas to the evil deeds, usually political, of the authors that I cite. Some evil men can write quite good books and some basically good men, or women can propagate some exceedingly silly ideas.

OLD HICKORY

1) Quotations from Chairman Mao (1966)

Mao Zedong

Mao was responsible for a great many premature deaths. The story is told in Mao (2005) by Jung Chang and John Holliday. If numbers matter then Mao was haply the acme of evil so far. Adding the millions lost in the 1950s during the so-called Great Leap Forward of some 40 million to the 50 million pre-mature deaths of Mao’s come-back, the so-called Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, gives us an unrivalled 90 million total, putting Mao top of this list of mass killers, and thus, of evil men. He was, clearly, a consummate politician. He died in 1976. Since then China has made some progress but, for many very inadequate reasons, most people in China imagine that things were worse prior to Mao’s rule. Had Hitler won the war, there might be a majority in Germany today that think he was a great man. Most “great men” today are held to be politicians, but as politics is internecine, any clear thinking person on the media, or amongst the wider public, would most likely see that there was no great man in politics at all, in that no one in politics has ever done much good in the world. Other men, in science, in the arts and in technology clearly have done very well in the legacy they have left behind.

Mao was the leader of the Red Army in the fight for control of China against the anti-Communist forces of Chiang Kai-shek before, during and after World War II. Finally victorious, in 1949 Mao founded the People’s Republic of China, enslaving the world’s most populous nation in a futile central planning schemes. It was those schemes that caused the 90 million pre-mature deaths.

Mao in 1935

Mao called himself a Marxist-Leninist. Marx had imagined that planning might be achieved if the giant firms superseded money in their internal economy, a thing that the drift towards bigger firms was bound to achieve given the tendencies he thought he saw in the market towards the greater economies of scale. What Marx overlooked was the diseconomies of scale. In any case, the giant firms never emerged; let alone a moneyless central planning that could replace money within those giant firms.

However, Lenin practically ignored the need to get rid of money on day one as he made a distinction between socialism and communism in 1917. With socialism able to both retain money and planning, communism, the society that would shed money, was put off to the far future, maybe indefinitely. This was contra Marx who held that money would upset any planning, even in the short run, but Mao was content with Lenin's practical revision of Marx.

Mao adopts the class struggle, but following Lenin's meme of imperialism, he also sees a struggle between nations too and seems to be as bit confused about the two. “The revolution, and the recognition of class and class struggle, are necessary for peasants and the Chinese people to overcome both domestic and foreign enemy elements. This is not a simple, clean, or quick struggle” we are told but the working man was supposed to have no country in pristine Marxism. Mao does not seem to realise the clash between Bolshevism and Marxism and he fails to see the ill fitting union of the new Leninist ideas to the old outlook. Instead he embraces the new ideas as they are nearer to common sense anyway. Lenin commissioned Stalin to write Marxism & The National Question (1913) that was the origin of the policy of "socialism in one country" and Mao follows Stalin on that; as on most things. Thus he says “ Socialism must be developed in China, and the route toward such an end is a democratic revolution, which will enable socialist and communist consolidation over a length of time. It is also important to unite with the middle peasants, and educate them on the failings of capitalism.” This effectively makes him a national socialist.

Mao sees war as a menace and realises, as did Lenin, that Clausewitz was right on war being politics carried over to the battlefield. “War is a continuation of politics, and there are at least two types: just (progressive) and unjust wars, which only serve bourgeois interests. While no one likes war, we must remain ready to wage just wars against imperialist agitations”, he tells us but he failed to see that ordinary politics was cold war and was also anti-social. Instead, he embraces the folly of war. But most of the killing he encourages was within China. “Fighting is unpleasant, and the people of China would prefer not to do it at all. At the same time, they stand ready to wage a just struggle of self-preservation against reactionary elements, both foreign and domestic”, he said, but he saw to it that it was mostly domestic thereby causing millions of premature deaths; more than any other politician so far.

2a) The Bible (c. 325; King James Edition 1611)

Myriad Anonymous, et al.

King James Version Bible first edition

This large anthology is more like a small library than a single book. As said above, it is excellent as literature but poor as history. As David Hume rightly said, “we can tell from any page of the Bible that it was written by ignorant savages.”

The canon was put together at the founding of the Christian creed as a state religion in the wake of the councils of Arles in 314 and Nicaea in 325. The book is harmless enough in itself, but if we count it as the supposed word of God and that it truly reports God’s actions in destroying whole towns, flooding the world and also giving a promise of fire and brimstone that is still due, then we might even feel that the Author is going to later overtake Mao as the most evil author even on his promise of the future. Indeed, as the maker of Mao, He should already be responsible for all that Mao did and would be well ahead of him in evil [even if He offset this by having done all things good too]. Mao is placed first here, on the idea that he was worse than anything merely religious, so far, and on the idea Mao actually existed. Religion only does damage when it gets political.

2b) The Koran (c.616)

Gabriel, Muhammad et

al.

11th Century North

African Koran

This is the latest new testament, or at least a later one than the Christian one, if we need to note the book of Mormon as a later testament still. We can put this with the above, (as joint number two), as it is thought to be associated with God and it is in the Biblical tradition. This is the sacred book of Islam and also called The Quran. It is written in Arabic and claims to be passively taken down by Muhammad as a mere amanuensis from the angel Gabriel, but some books on it report a more mundane origin, involving many more men and one less angel. It is the supposed word of God , as is the Bible. The books are harmless in themselves, but they have inspired a great deal of intolerance, whenever the adherents get political.

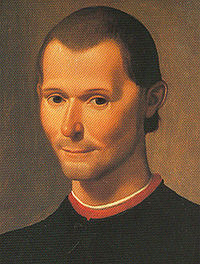

3) The Prince (1513)

Niccolo Machiavelli

This book has been eulogised as realistic by many admiring political nitwits, who seem to habitually overlook the internecine results of the political activity that the book perversely celebrates. It glorifies a brutal realism that is naked politics. It holds that the state is such a supreme end in itself that any ruthless activity and a preoccupation with war is made virtuous merely by being a political necessity. The author boldly embraces political realism and any activity that aids political success. His frankness is achieved merely dropping the normal cant or special pleading of politics.

Niccolo Machiavelli

The author, Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527), had a few ironies in his lackey-like life. Machiavelli loved the state but had hated the ruling Medici family, maybe because he lost his job when they came to power in 1512. He, nevertheless, attempted to court them, but his name was found by the Medici on a list made by some republican opponents of the Medici, as being one of many involved in a plot against them, So they arrested him and tortured him. Eventually, they let him go and he went off to a farm exile from where he pleaded for a new job in the state of Florence. It was during this fourteen years of pleading from the farm exile that he wrote the book under review, oddly advising against flatterers when the book was a piece of flattery in itself. In 1527, the armies of Charles V brought the Medici down but on hoping to get a job in the new republic the flattering book under review made it known that Machiavelli was hardly fit for such a job. As chance had it, he fell sick and died before the new authorities informed him that they thought him to be a scoundrel.

4) Blueprint for Survival (1972)

Edward Goldsmith, et al

A scary story from 40 years

ago

This is representative of the remarkably silly Green outlook that perversely opposes economic growth as an end in itself. It is a reproduction of the entire issue of The Ecologist Vol. 2 No. 1, January 1972, in advance of the world's first Environment Summit: the 1972 UN Conference on the Human Environment, in Stockholm. The principal authors were Edward Goldsmith and Robert Allen, with additional help from Michael Allaby, John Davoll, and Sam Lawrence. It was later published as a Penguin Special. It is on par with the Club of Rome's slightly later Limits of Growth (1972).

One might have expected the reply by John Maddox and others at Nature, then the top science journal in the world, to be published in the same book, as Penguin were supposed to be impartial. The eventual reply, The Doomsday Syndrome (1972) John Maddox, had to wait until later as Penguin never were impartial but biased towards the Greens and what has been called the left since the 1880s i.e. statist ideas.

The Green idea is often thought to spring from the Essay on the Principle of Population (1798); second much expanded edition (1803) by Thomas Malthus but that is not so clear if we pay attention to what Malthus actually said. He was certainly not against economic growth. Malthus did have some rather silly ideas on human population growth but he also was keen on individual liberty and against the injustice of welfare.

I will give a short account here of what Malthus actually said in his second greatly expanded edition of 1803, much of which is devoted to curbing the Poor Laws. The second edition was much revised from the even more pessimistic first edition of 1798 [which, sadly, I do not have] to include the moral restraint that differs humans from all the other animals and the plants, a distinction he neglected in the first edition. Here Malthus states the thesis that any species would grow in population indefinitely but rival species cut this off in a war of all against all. Thus, population growth is checked by rival populations. Malthus says that Benjamin Franklin had this thesis, so he admits that it is not new to him, and it is stated as a natural history thesis Essay On the Principle of Population (1803 [1958 Everyman edition] ). Malthus says: “It is observed by Dr Franklin that there is no bound to the prolific nature of plants or animals but what is made by their (p5) crowding and interfering with each other’s means of subsistence. Were the face of the earth, he says, vacant of other plants, it might be sowed and overspread by one kind only… This is incontrovertibly true.” (p6).

Thomas Malthus

He goes on to put the growth of human population in geometric terms but food produced by progress in agriculture to be arithmetical by contrast. Both have no upper limits but we get a Malthusian cutback to food levels regularly. Contra his critics, be they Julian Simon or Edwin Cannan, Malthus asserts no limit to growth in the long run at all. He is not like Sir Edward West, on Cannan’s account of West. Cannan holds that it is a myth that Malthus ever thought or even knew of diminishing returns at all, and that seems to be the case. He says that that it was West who pioneered that idea. West holds that we will get diminishing returns, in any case, even if we cut back on population growth, but Malthus holds that famine will only check the steep rise from time to time, whenever it outpaces the food supply and it will then continue up from there after each Malthusian cutback. As Malthus explicitly says: “In this supposition, no limits whatsoever are placed to the produce of the earth. It may increase forever….”(p11). So it is not true what they say about Malthus.

The Green team at the Ecologist held that economic growth could not go on and that sooner, rather than later, it would be displayed as not sustainable. Malthus thought that many famines would be almost unavoidable and population would take a dip. But he did not think there was any upper limits to long run economic growth, or even to population growth. He merely thought that population would grow beyond the means of subsistence many times a century and would face a Malthusian cutback to food levels whenever that happened But those would be set-backs in the overall upward growth of population.

The Greens, by contrast, held to the common sense idea that resources were finite and economic growth exponential so it was merely a matter of time before a breakdown occurred. This breakdown would come within the lifetime of people born by 1972. Economic growth is oddly said to impose misery on most of mankind. But the precise time of this doomsday could not be given. Either we can leave it to famine, wars, disease and chaos to end economic growth or we can go Green and end it in a planned way. The Greens wanted to end it in a planned way.

There was, already in 1972, large scale overpopulation, said the Greens. This would need to be cut back to sustain natural eco-systems. As things were going, even with replacement levels only, the population would be 15.5 billion by 2040; that was over four times the 1972 size, claimed the Greens.

Economic growth left to itself would simply grow and grow without limit. Oil will run out soon if this is allowed to go on. The environment is having too much taken out of it and is being polluted too. Both the taking of resources and the imposition of pollution was called by scientists at the MIT in Boston USA the ‘ecological demand’. This seemed to them to be doubling every 13.5 years. The world cannot accommodate such an increase, the Greens said. Resources are finite so there just must be a limit. “This is the nub of the environmental predicament.” It will look as if all is fine, as it might to a frog being slowly boiled, but then the doubling of population levels will be suddenly unsustainable. This is bound to be the case with exponential growth, given finite resources. That is why we needed radical Green action in 1972, said the Greens.

The Greens gave consideration to the disruption of eco-systems. We depend for our survival on the predictability of ecological processes, they told us. The eco-systems are predictable and the ecologists have been able to see the danger ahead. All ecological systems establish stabilising equilibrium, the more complex such a system is, the more stable it will be for the more species there are, the more they will inter-relate with each other. But those systems are messed up by modern farming with its unnatural chemical insecticides. The use of DDT, in particular, has produced a damaging monoculture that tends to destroy the natural eco-systems. Many species have gone extinct as a result, they claimed.

There were, in 1972, about half a million chemicals in use in farming. All were used at somewhat of a risk, for the effects of them were not fully known. Nor were the combinations of them put into the environment known, but it was clear to the Greens that they endangered a lot of wildlife, up to some 280 mammal, 350 bird, and 20,000 plant species were supposedly in danger by 1972. The Greens noted that some people thought it worthwhile for man to thrive, but the Greens held that man too was being threatened by this damage to natural habitats. In adapting nature to man rather than adjusting to the natural eco-systems, man was being unwittingly suicidal.

Already by 1972, food supplies were failing and the land was left barren. There were new high yield wheat and rice in the offing but they were subject to disease and required even more pesticides and fertilisers in ever more intensive farming if ever they were to flourish. If they did then they would upset the natural eco-systems more than ever. The result could be a world of one or two species, acting as a food factory for man, predicted the Greens in 1972. And it seems inevitable that food is soon set to decline throughout the world and then Britain would no longer be able to import food from other lands. Severe food shortages are due in the next 30 years from 1972, so things would be dire by 2002, they told us back then.

On the idea that continued exponential growth of consumption of materials and energy is impossible, the Greens felt they could say that the present reserves of all but a few metals would be exhausted within 50 years from 1972 – about 2022. New discoveries and advances in mining technology might help, the Greens admitted but, at best, they would only allow for a limited stay of execution. Continued exponential growth of consumption of materials and energy was impossible. But even if energy resources could go on infinitely, the problem of accumulating heat would be the eventual result that would still doom us. Here we have the Global Warming meme even back in 1972.

In order for the poor in other lands to do better than they were doing in 1972, say the Greens, the rich must cut back. It is not fair, they say, that the rich lands have so much more than the rest of the world. Anyway, there is too much capital and that leads to mass unemployment in the rich lands. Shades of J.A. Hobson there. Soon many will be thrown out of work, they told us. The unemployed are bound to make trouble for those with jobs, the Green expect.

As the mass urban society becomes demoralised, the Greens think that we can expect diseases to wipe out millions of people. So they expected lots of epidemics to cut population levels back. It is not likely that the modern society could cope with the many diverse diseases. With decreasing supplies, they expect that war will be seen as a means of getting better food at the expense of neighbouring lands. Nuclear bombs might be used to that end. This was far more likely than the naïve optimistic outlook that the Greens opposed, for that assumed that all in the world could live at 1972 USA standards. Ecology shows us that that is not even remotely an option, the Greens held back then. And they still hold that today, and say that we need to adapt to nature rather than trying to adapt nature to us. They held that there was an impending crisis in 1972. Conventional technology can only upset ecological systems even more. Economic growth can only boost human population growth, at least in the short run. That will make things worse as it means more capital for more jobs. No government can tolerate high levels of unemployment so it will set out to stimulate yet more economic growth. If this growth stopped then society might collapse owing to discontent. So the Greens expected governments to continue to promote economic growth. In this way, natural disaster was unavoidable.

A new Green plan will be needed to get round all this, they said. The Green task in 1972 was “to create a society which is sustainable and which will give the fullest possible satisfaction to its members.” This society would need to give up economic growth and aim, instead, for stability. Such a society need not be stagnant, and it could be full of diversity making a stable use of technology. This would be a better society, claimed the Greens in 1972, and so they have been claiming ever since. Indeed, they have continued an opposition to the mass urban society begun by the Romantics in the late eighteenth century, who opposed the process of industrialisation that later Romantics, like Arnold Toynbee, called the Industrial Revolution.

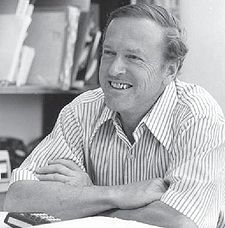

Julian Simon who demolished Green claims in his book The

Ultimate Resource.

There is an interesting contrast between the estimates of resources made by natural scientists and engineers on the one and the likes of Julian Simon, who makes economic forecasts, on the other hand. I largely follow Simon [The Ultimate Resource II (1996) p.41ff] in the rest of what I have to say here and below. The Greens feel way superior in backing the former engineering group but it has cost them a history of shouting wolf repeatedly since 1965 when there has been, as yet, no wolf at all.

Why have economic forecasts done way better than the engineering ones that the Greens rely on over the last forty or so years? The answer is that the economists use market research, which is more active research than the research done by the scientists and engineers. Because the market research is more diffuse, or distributed, or polycentric, than the academic research it is thereby more extensive. The economic research has been way more favourable, or optimistic, than that which the Greens rely on. There is wide variation amongst all sorts of forecasts, in any case, and the two sorts cited here can often overlap.

Engineers tend to rely on physical measures by estimating the quantities and the quality of the resources in the earth and they look at the current methods of extraction to predict how things will be in the future. They calculate the future costs from present costs, or from best estimated future costs on the idea of how much of a given resource that there is. They assume there is a limit to growth. Common sense tells them that this just has to be the case. But resources are diffuse, such that it is not so simple to get a sound gauge of the whole of any one resource, so we practically, settle for resources that we can effectively tap. This usually falls far short of the whole of the physical resource. We cannot clearly gauge the whole amount. It is easier to think of doing than to do. Instead it falls to what we can use; or what we know of so far.

But once we look at usage then the utility we gain from the resources becomes more germane than the physical or technical resources that we have. For most goods we continually use substitutes in what we produce anyway, and few amongst the scientists even note that fact; let alone amongst the wider public that forge current common sense. We often, effectively, create new resources by innovating economies in the way we use the current resources. We also make new finds in resources that we never knew about earlier, North Sea Oil was freshly found in the 1960s, for example. It was once thought that there was no oil in Texas. It may even be that we get some resources from other planets in the future. And it was not always known that oil was even a useful resource. Oil became a resource as we became aware of what it could be used for. It was created as such by ideas and insight; by human beings who thereby show themselves to be the ultimate resource.

Nuclear power can supply much of the utility that we get from oil so it may well be that oil will not run out before we move on to some substitute, just as we never ran out of stone in the Stone Age. It is not that resources are available so much as we tap an array of various substitutes for some utility that high prices drive many to search for by putting a bounty on fresh innovation.

In the naïve outlook, then, resources are simply natural and available in a finite amount. The reality is that we learn to use what we find as a resource by fresh innovation to fit the use that civilisation then has for it. This suggests that the full array of resources are not so clearly finite. We do not even know what resources are out there, just as our forefathers never knew about the potential usefulness of oil. We do have a dominant theory in physics that any matter whatsoever is full of energy: E=mc2. Natural resources are only fixed in the short run, based on our inadequate current knowledge. There is no time when we can get the sort of total limited supply that the Greens feel just must be the case and as current common sense also holds must be the case. That case can only be based on ignorance.

Then we get challenges from some scientists to the idea that oil is a fossil fuel at all, such as we can find in The Deep Hot Biosphere (1992) Thomas Gold. This book holds that oil arises from the secretions of microbes and thus is quite renewable.

Thomas Gold.

Often forecasts are simply based on looking at the known reserves with the current demand and usage to gauge how many years of reserves that we have left. This will have its short run uses, prompting suppliers to ask how useful it is to search for more. But this does not relate to distant future resources. and it will not be at all likely that the years postulated will be all that there is truly left for future usage. Resources can often increase rather than decrease, despite being in increasing demand, and stockpiles of many resources have increased since 1950. It is not the case that if we gauge that we have only 15 years left at current usage that we will therefore run out even in the next twenty years, even if usage increases as it so often has since 1950. The main seemingly rock solid Green assumption is merely unrealistic. It is based only on current knowledge but in counting even the most diffused elements of any resource it also overestimates what we can practically use as well as not looking at what we may find in the future. We may never use many dispersed elements of a resource in the oceans, for example.

The Green criterion tends to overlook the fact that supplies can increase in response to price rises as well as substitutes also thereby being boosted. Yet a small price rise can make a big difference in supplies. The Greens often overlook that they are only citing supplies at current prices. They often expect that the easy supplies will be extracted first and then after that it will get increasingly difficult to mine many resources. But the last 300 years, it has been scarcity that has been decreasing as better methods of extraction more than match the increasing difficulty of extraction. The result has been that mining resources gets ever easier and cheaper.

When technical forecasts attempt to go beyond known reserves, they are very speculative but the economists bear in mind the likely costs. And the engineers tend to see costs as disincentives rather than as incentives, though they are often the latter. The engineers usually overestimate their own expertise on the division of labour and show undue caution in their forecasts. This leads them to underrate the progress that is likely to be made in the future though it is, of course, quite true that it is logically possible that we might make no progress at all from now on. It is also logically possible that we will all live forever from now on. The economists tend to be more realistic than the engineers when they assume that costs will continue to decline in real terms in the long run as high short run costs result in shortages which in turn increase long run supplies.

Engineers tend to overlook how much they have learnt from the stimulus of the price system. The estimate of known reserves has been largely mustered owing to the incentive the price system provided to survey the resources that there might be. A future price rise may well stimulate a more thorough survey than we have undertaken hitherto. We simply have not made the sort of full survey that the naive Green, if that is not a pleonasm, assumes with his fresh cry of wolf. We have yet to do anything like the sort of survey that the Greens often imagine was done long since.

Ideally, we would like to know how much of each raw material could be produced at each market price in each year due hence. It will depend mainly on the supply and demand due at any given future time. As resources get scarcer the price tends to put a higher bounty on finding more of the resource and any alternatives there might be. But success in this quest may well increase stocks world-wide rather than lowering established stocks and that has been the case up till now since about 1700. So the real price may go on falling, as it has those past 300 years, or so.

Known reserve surveys tend to ignore prices even though they have been stimulated by prices in the first place. To that extent, they tend to be unrealistic. This continuing falling prices in real terms tends to refute the Green outlook. Any rise in price will tend to put a bounty on solving the shortage that gives rise to it. It does not look like resources are due to run out any time soon and the dogma that they just must do so sooner, or later, owing to usage being potentially infinite whilst natural resources are merely finite is misleading and hardly worth bothering about, as we might realise if we ironically do seriously bother about it.

Current surveys are ad hoc rather than definitive. But even if we did have definitive surveys they would not be as informative as the Greens imagine, as there are many substitutes and cost cutting innovations that might well be made in to replace any current usage, such as when we replace copper in telephone lines with fibre optics, or replace the use of oil by nuclear power. We cannot forecast when a shortage will constitute a Green wolf; maybe it never will. The story, so far, has been one of continuing falling prices and increasing abundance. The price system over solves short run shortages to increase long term abundance. Statistical data indicates that that has been the case since about 1800 and history suggests it goes back way further than that.

But should a Green wolf ever arrive then far from this indicating that we need to abandoned the market economy, as nearly all Greens urge, the great new shortage will instead merely affirm a greater need for economy and thus for the price system. There is no disaster that will require the greater political and totalitarian society that most Greens long for. Their imagined solution to the imagined Green wolves are invariably set to impose a worse problem on society than any of the wolves that they have so far imagined. Their statist solutions always look as inept as a sledge-hammer would be to open a peanut. The Greens make the problem look mild in relation to their longed-for masochistic “solutions”.

There is always the logical possibility that any cry of wolf by the Greens could be correct in any current instance so some slight look needs to be taken each time, but we can realistically expect the cry to be as insubstantial in the future as it has been in the past.

5) Mein Kampf (1926)

Adolf Hitler

First Edition of Hitler’s best seller

The book My Struggle (1926) was initially published in two parts in 1925 and 1926 after Hitler was imprisoned for leading Nazi Brown Shirts in the so-called “Beer Hall Putsch”. He had attempted to overthrow the Bavarian government. He was given an opportunity to write down his ideas and he produced this long verbose book that has little merit apart from letting us know what the author thought well before he achieved power in 1933. This book only became important as the author became the ruler of Germany and he then set out to make a big impact on the world by causing no end of trouble. Hitler was the perfect politician. He was a true Machiavellian in holding that whilst public support was an important prerequisite, their personal interests were not so important and the glory of the state was all. It was once said, on a television programme in 1983, that John Fitzgerald Kennedy cribbed his perverse Machiavellian inaugural address statement from Hitler's speeches viz. “And so, my fellow Americans: ask not what your country can do for you - ask what you can do for your country.” That this perverse statement was applauded in the USA of the 1960s, and fondly looked back on ever since, shows how far we are from liberty.

There was another television programme called Young Hitler in 2005, I think, where we were told that Hitler rather liked the Jews up to 1919 largely owing to his love for a Jewish female but that he took part in the Spartacus uprising led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, who were both Jews. Hitler only turned against the Jews after he was caught in the aftermath of participation in that uprising as one of their followers. Hitler testified against them to be excused from punishment, we were told, and, from then on, he remained steadfast against the Jews. Iain Kershaw was one of the advisers for this programme but this story was not found in his book by me in the days following the broadcast, and nor elsewhere in any book on Hitler Parts of it did emerge in a few articles in the newspapers, two in the Daily Mail, by the historian Andrew Roberts.

Anyway, by the time he wrote My Struggle Hitler was very anti-Jewish [anti-Semitic would be anti-Arab, but most Jews are clearly not Arabs and Hitler only had it in for the Jews] and this outlook is rather crankish in that it sees all sorts of things as Jewish.

Hitler sees liberalism as a Jewish outlook, especially in the Manchester version, though Richard Cobden was an apathetic member of the Church of England and John Bright a member of the Society of Friends. Hitler felt this liberalism had reached its acme in Austria in the Dual Monarchy, when nationalism reacted against it. It was not owing to social causes, as many authors imagine, but to the idealism involved in nationalism, says Hitler. Two parties emerged where one was outrightly nationalistic and the other a bit more social but both were more to do with the future than was the barren pristine liberalism. This idea of nationalist idealism may well be the case. Nationalism is much misunderstood and often underrated by both liberalism and the liberal heresy, if there can be such a thing, of pristine Marxism.

![]()

Top 50 books of all time : by Old Hickory:-

"I have limited the selection to the books I have read. I keep to the norm of not recommending to others books I have yet to read. Clearly, books I have not read by now suggests a judgement of some sort."

The Alternative

Bookshop

Which specialises in,

but does not limit itself

to, books on Liberty

and Freedom ... Book

reviews, links,

bestsellers, rareties,

second— hand,

best price on books,

find rare books.